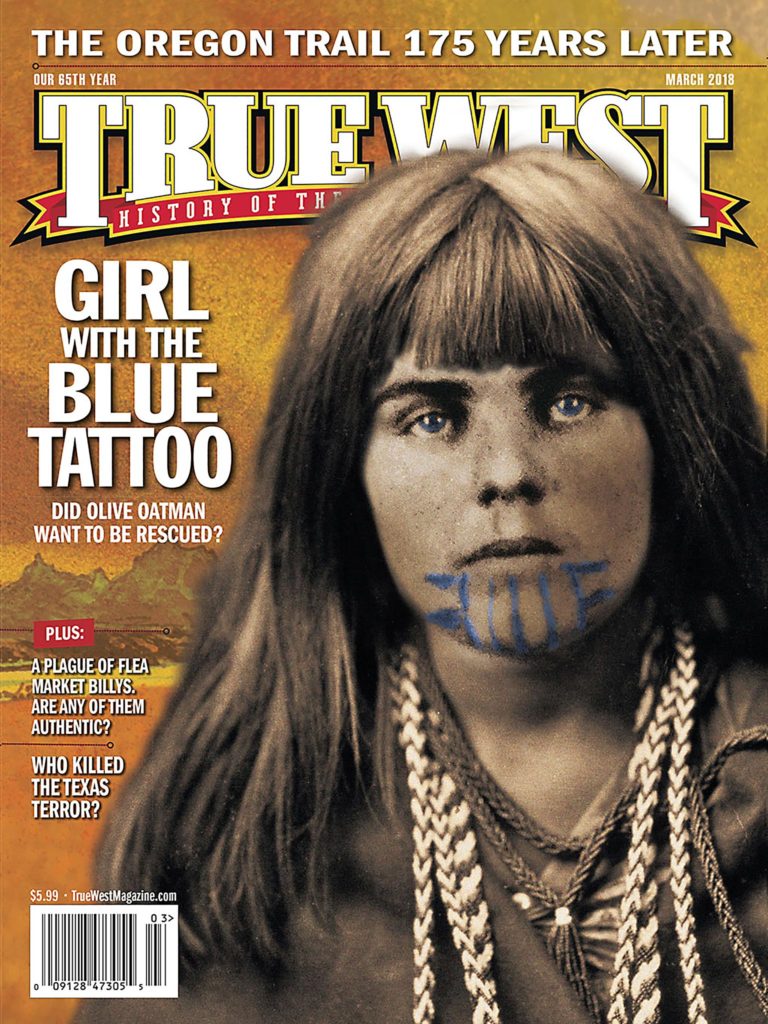

The conversation all started with a letter from my hometown, Buffalo, New York. Rob McElroy had sent a note to the Yahoo group “Photo History” about the latest mystery, writing, “Another indistinct tintype has surfaced that purports to show Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett in the same photograph. There isn’t any credible proof for that assertion except for the less-than-qualified opinions of two so-called ‘experts’ whose names many here will recognize.”

Then McElroy shared a link to The New York Times article from November 16, 2017, telling the story of yet another flea market tintype purported to show not only the famous New Mexico Territory outlaw Billy the Kid, but also his killer, Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett.

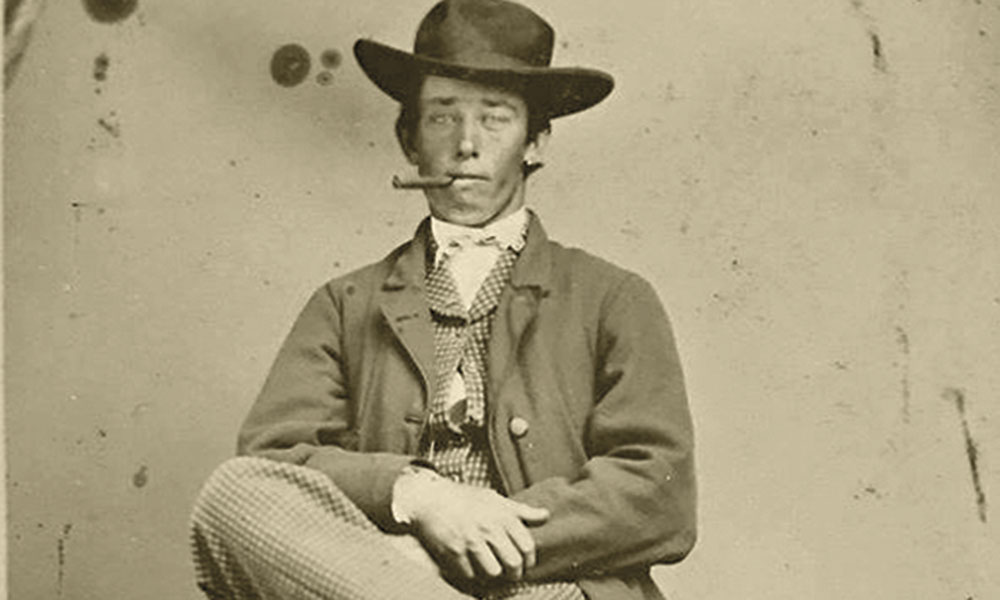

This was not the first time we have seen this tintype. The owner, Frank Abrams, a criminal defense attorney in Asheville, North Carolina, brought a scan of the tintype he had purchased for $10 at Smiley’s Flea Market in Fletcher into the magazine’s headquarters in Cave Creek, Arizona, in August 2017. He wanted to get feedback from our executive editor and acknowledged Billy the Kid buff, Bob Boze Bell.

Why visit our magazine? True West had earlier featured a tintype Randy Guijarro purchased for $2 at a flea market in Fresno, California, in 2010. By 2015, Guijarro had convinced the National Geographic Channel to tell its story, and the network had convinced actor Kevin Costner to join the project as executive producer and narrator. In our February 2016 issue, Features Editor Mark Boardman shared the controversy behind this “Croquet Kid” tintype—so-called because this Billy the Kid was holding a croquet mallet, surrounded by several other men, women and children—and provided an excellent analysis for our readers to decide for themselves if the tintype was indeed an authentic photo of the Kid.

Why are all these flea market Billys coming out of the woodwork? The only-authenticated tintype of the Kid sold at Brian Lebel’s Old West Auction in 2011 in two-and-a-half minutes for $2.3 million. Western art collector William Koch had made history, paying about $460,000 a half square inch for the roughly three-inch-by-two-inch Kid tintype.

Who wouldn’t want to make millions off a piece of history? The debate over any historically important photograph is serious. Solid provenance could mean a huge chunk of change.

Dan Dedrick, whose tintype was included in the Kid lot that Koch purchased, was a pal of the outlaw’s, and the Kid tintype traces directly to him. Historians didn’t just trust Dedrick’s claim that this showed the Kid; the tintype was identified as him during the Kid’s lifetime in the Boston Illustrated Police News in January 1881. Even more, the man who ended the Kid’s life that July, Sheriff Garrett, published the same photo in an 1882 book he partly wrote, The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid.

When Abrams found out that “experts” had valued the Croquet Kid tintype at $5 million, he decided to take a closer look at the tintype he had bought at a North Carolina flea market. He turned to a familiar name, Kent Gibson, who concluded the Kid and Garrett were in the picture.

Who is Gibson? He’s the forensic scientist who’s worked with the FBI and the U.S. Secret Service who came aboard the Croquet Kid project as the facial recognition expert. In the National Geographic Channel show, he shared how he had used facial recognition technology to compare known photos of folks he concluded were in the tintype: not only the Kid, but also his acquaintances, Charlie Bowdre, Tom Folliard, Sallie Chisum and Paulita Maxwell. But Gibson also said of his identifications, “In a court of law, I would have to deny it. It’s not detailed enough to make it a really valid image.”

You can imagine how the reappearance of Gibson set off the folks in that Yahoo group “Photo History.” Daniel Buck, who, with his wife Anne Meadows, has dedicated time to tracking down the whereabouts of notorious bank and train robbers Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, was the first to respond to McElroy.

“Your skepticism is well-founded,” Buck wrote. “Billy boffins are laughing at this tintype….”

You may feel this is a fight between experts, the so-called Kid experts who include biographer Frederick Nolan, and forensic and photograph experts who include Gibson. Why is one side more valid than the other? To be clear, we are friends with many of the Kid experts, but we also aim to stick to the facts. And we believe the Kid experts because that is their aim as well. In this case at least, they are not drawing backwards to figure out how a photograph could track to a person; they rely on direct ties and contemporary confirmations.

Gibson, on the other hand, has made the news authenticating another photograph. Not an Old West one this time, but an out-of-focus photograph showing several people on a dock, including, he claimed, the famously disappeared Amelia Earhart and her navigator after the Japanese captured them—despite the fact that Earhart has her back to the camera. As Buck puts it, “The pixels were hardly dry on that story when a Japanese researcher found that the photo had been taken a couple of years before Earhart’s 1937 flight.”

Now just because an authenticator has made a few false calls does not automatically disqualify his work. But basing a claim on forensic science alone is not an accepted method of provenance. Ask any major auction house.

When these debates over alleged photos showing famous people happen, you can get in the weeds pretty quickly. Folks in the Yahoo group, including Phil King, Edward J. Lanham and others who had also added to the debate on the Croquet Kid, talked about the envelope that accompanied the Abrams tintype. On it was writing that might suggest this tintype is linked to a family in Lusk, Wyoming: “Lusk Root” and “B.A. Root.”

The crew tracked down Judge Benjamin A. Root in Lusk, Wyoming, who lived there around the same period of time the tintype was allegedly taken. (Tintype expert William Dunniway told The New York Times that the Abrams tintype was taken between 1875 and 1880.)

Lanham tracked down an obituary that stated Root had been born in Royalton, Vermont, on April 23, 1842, and that he had moved from Vermont to Iowa in 1878, then to Nebraska and finally to Wyoming in 1887, where he became justice of the peace in Lusk.

Abrams has countered back that “Root” could refer to Elihu Root. Abrams purchased the alleged Billy the Kid tintype with four others, including one that came with an “Eddie F. Root” calling card and a note, stating, “This came from Clinton, N.Y. perhaps a member of Elihu Root’s family.”

Why is that connection important? Abrams has learned that a Root family member married an Upton family member, possibly providing the link to Ash Upson. Upson, of course, is the ghostwriter who assisted Garrett in his Billy the Kid biography.

In his tintype, Abrams has identified the second man, with the bulging Adam’s apple and signature sweater (he wore a sweater in the only-authenticated tintype), as the Kid. The man at the far right, with a mustache, he identifies as Garrett. He also thinks the man in front, clutching a pistol, is “Dirty Dave” Rudabaugh and the man in the middle could be cattle rustler Barney Mason, other Kid acquaintances. He speculates that the tintype could have been taken on January 14, 1880, the day of the double wedding of Garrett to Apolinaria Gutierrez and Mason to Juana Madril.

Again, we are going to leave the decision up to you, our readers, to determine whether or not you believe this tintype shows the Kid or any of the other Old West characters identified by Abrams and others.

We do have one request, in terms of debating historical photographs. This can be a fun parlor game that may even result in an honest-to-goodness identification that changes our understanding of history. But let’s cease on the personal attacks.

You may think folks are above name calling and sending hate mail in the interest of pursuing the truth, but apparently not when millions may be at stake. Everyone at True West hopes we can all conduct these conversations with respect and acknowledge everyone’s right to chase the facts in the way they feel will produce the best outcome for the historical record.

Hearing about a new Kid image is pretty common at the magazine these past couple of years. Maybe the appeal to find another photograph of the outlaw will never die out. A description of him, when The New York Times reported the Kid’s death in 1881, crystallizes why: “His soft blue eye was so attractive that those who saw him for the first time looked upon him as a victim of circumstances. In spite of his innocent appearance, however, Billy the Kid was really one of the most dangerous characters which this country has produced.”