She had to be shocked from the top of her flowered hat to the hem of her velvet dress. This can’t be happening, she must have thought, not after all we have done together, not in this town I helped grow.

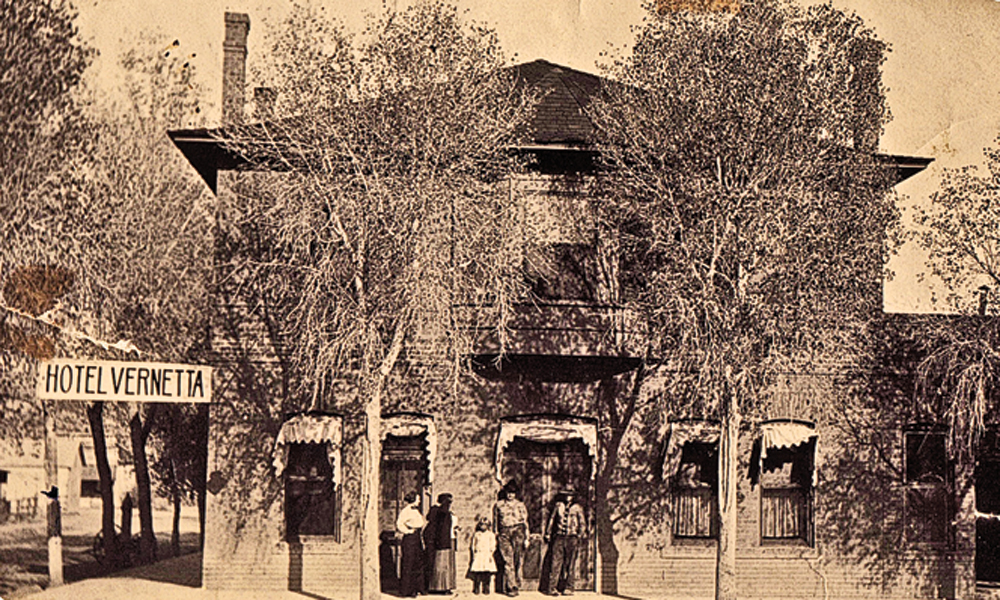

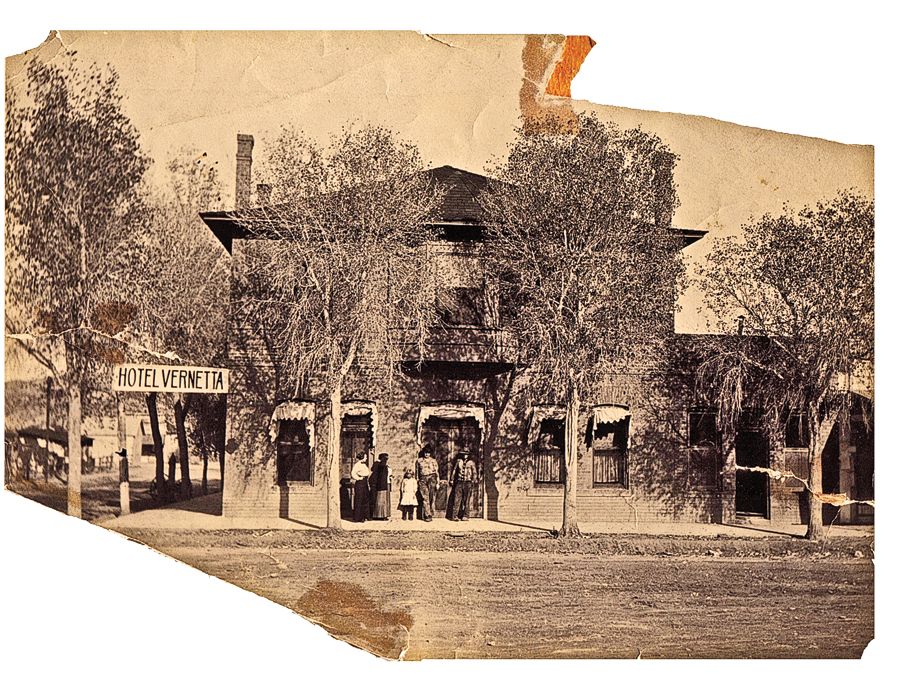

Elizabeth Hudson Smith must have felt dismay when her world in Wickenburg, Arizona, turned upside down in the 1930s. When prominent men and women she had befriended for more than three decades crossed the street to avoid her. When her beloved Hotel Vernetta—the town’s unofficial community center since she built it in 1905—was shunned.

Did she cry when the First Presbyterian Church she helped create told her she was no longer welcome? Or when the Opera House she built was ignored by theatregoers?

Perhaps Elizabeth took all this in stride, secretly fearing that this day would come. The pioneer black female entrepreneur surely knew that Arizona held its prejudices, with a history of discrimination against anyone of color—first the Indians, then Mexicans, Chinese, blacks and the foreign-born.

But none of that racism had touched her here. Until tough times during the Great Depression left her an outcast in her own town. The worst and final indignity of all was one she at least never knew.

An Alabama Gal

Elizabeth Hudson was born in Alabama—her birth date remains a mystery. Her tombstone states October 3, 1869, but in three Arizona census records, she gave different dates—1874 to 1876 to 1877. Her mother’s identity is unknown, but Elizabeth was the daughter of Sales Hudson, who was born a slave on a Kentucky plantation.

Her father, freed by the Civil War, encouraged his daughter to get an education. Elizabeth read, wrote and spoke French. She was also a natural businesswoman, with a head for figures.

On September 16, 1896, she married Bill Smith in Chicago, Illinois. Bill was a porter on the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway—some claimed he was the personal valet to George Pullman, who invented the Pullman sleeping car.

The newlyweds sought a new life in Arizona Territory and took the train to Wickenburg, a town founded in 1863, after German gold hunter Henry Wickenburg struck gold at the Vulture Mine—the richest gold mine ever discovered in Arizona.

As the train pulled in on an August night in 1897, the Smiths found themselves among a few hundred souls, but one of the most diverse mixtures in the territory—Mexicans, Asians, Indians, miners of all ilk.

The Smiths, possibly the town’s first black citizens, sought shelter at the run down Baxter Hotel. Bill Baxter joked that his guests threatened to lynch him for lousy service and indigestible food. Promising they could improve the hotel’s lot, Elizabeth got hired as the cook and Bill as the bartender. Elizabeth’s cooking attracted both townspeople and visitors; her “decadent” chocolate chip cookies sealed the deal.

But Baxter was still saddled with a dilapidated, 1860s adobe building he did not want. He said the place was as reliable as a drunken cowboy on Saturday night, but Elizabeth and Bill jumped at the chance to buy it. They added a second level, giving Wickenburg its first two-story building.

The improved Baxter attracted the attention of the Santa Fe railroad, whose tracks were a few blocks away on Railroad Street. Railroads did not yet have dining cars, so having a good hotel and restaurant near an overnight stop was a plus. Santa Fe officials approached Elizabeth to build a new hotel closer to the tracks.

She and Bill had already spent all their money expanding the Baxter, but they found money for this venture. Pullman was rumored to provide the financing. More likely, though, Bill used the proceeds from the sale of his deceased mother’s home in Chicago, since he and Elizabeth named the new hotel after his mother, Vernetta.

Wickenburg’s Best Business

Elizabeth hired Phoenix architect James Creighton, one of the territory’s first architects, to design the Vernetta. His credits included Old Main at the University of Arizona in Tucson and the Phoenix City Hall.

Creighton designed a two-story, red brick building that lodged 50, with six smokestack chimneys for fireplaces and wood cook stoves. He made the walls 12 inches thick to keep out the Arizona heat. To commemorate the Presbyterian faith he shared with Elizabeth, he embedded a cross in the lobby floor. The hotel was Wickenburg’s first brick building and the “best in town,” the local paper bragged.

Santa Fe railroad officials were so happy with the Vernetta that they built a wooden sidewalk from the train station to the hotel’s front door. Elizabeth greeted travelers who arrived, while Bill operated the Black and Tan Saloon in a corner of the lobby, which was filled with businesses, including a bank branch for cashing checks, a post office, a shoeshine stand and a radio repair shop.

While Elizabeth was doing just fine in her business life, her marriage was a failure. Bill’s love of the bottle had always been a problem. He would get drunk and disappear for days or weeks. One day, he never returned, and Elizabeth divorced him in 1912, citing desertion.

Elizabeth remained a jewel in Wickenburg’s crown. She not only hosted many community events in the hotel, she also helped bring culture to the town. She opened an Opera House where, by 1909, she was bringing in touring theatrical companies and local minstrel shows, sometimes appearing in the cast. The town had never before offered such grand theatre.

Elizabeth proved to be an astute investor. She saved enough to buy both a ranch outside town and a truck farm to provide meat and vegetables to the hotel. In town, she bought up commercial buildings—a restaurant, barbershop, a dozen rental homes—as well as a score of mining claims.

She was building up the town of Wickenburg in a state where the races could not intermarry; black children went to segregated schools; American Indian children were forced into boarding schools to teach them “white ways”; the pay scale for minorities was a fraction of that for whites; laws were passed to limit job opportunities for anyone of color; programs expelled the Chinese; Indians were not allowed to vote; and Mexican-Americans had to take a “literacy test” to qualify for the voter registry. Yet, for more than three decades, those prejudices paid her no mind.

Then all her success came crashing down, along with the stock market that ushered in the Great Depression.

A Stranger Among Friends

To this untamed land where people were once judged more by what they could do than by the color of their skin, civilization arrived, bringing with it incivility.

Wickenburg attracted whites from the east and south who did not view Elizabeth as a community leader, but as a black woman. People stayed in “white” hotels, instead of the Vernetta. With everybody clamoring for the few jobs available, the bias against minorities intensified.

Even so, how could a town so easily forget everything Elizabeth had accomplished for the community in all those years? Other black women had remained cherished in their Western communities. For example, Clara Brown, the “Angel of the Rockies,” whose funeral was attended by the governor of Colorado Territory. And Biddy Mason, a former slave who ended up owning a hunk of downtown Los Angeles and whose life story is still taught to California fourth graders. Wickenburg, instead, cast aside one of its most ardent community builders. Her story almost disappeared from the town’s history until 1998, when town historian Dennis Freeman revived her in a play he wrote, “The Wickenburg Way.”

Elizabeth went “underground,” said the now-deceased Freeman, on Arizona PBS in 2005. “She had to dress in the clothes of a maid in her hotel just because [townsfolk] didn’t want her to be too uppity.”

Elizabeth’s fortitude and smarts during this oppressive ordeal were enough to keep the Vernetta going; her hotel did not close its doors until Elizabeth died on March 25, 1935. She left an estate worth $50,000—equivalent to more than $860,000 today. The Hassayampa Sun’s obituary lauded her “many deeds of kindness to the community.”

But Wickenburg refused to bury Elizabeth’s body in the main cemetery, with townfolk claiming the resting place was for whites only—a far cry from the reception her mother-in-law had gotten in Springfield, Illinois. Vernetta had the bastion of Civil Rights among her grave mates at Oak Ridge Cemetery—Abraham Lincoln.

Elizabeth’s body was buried in the Garcia Cemetery outside town, alongside deceased Mexican-Americans, Indians and Asians, many of whom had also been her friends.

Dismayed over how her life had ended, Freeman revealed Smith as a “deeply responsible, wonderful flower of a human being” in the guise of actress Mary Kelly. But nothing Freeman wrote could compete with the poignant scene from opening night.

Tony O’Brien, the oldest man alive in Wickenburg, had been a friend of Elizabeth’s. After the performance, Freeman remembered, the elderly man walked to the stage:

“His face was wet with tears, and he stood in front of Mary and said, ‘Elizabeth, it’s me, Tony.’ And he put his arms around her, and for a 20-foot circle around those two, everybody burst into tears.”

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.