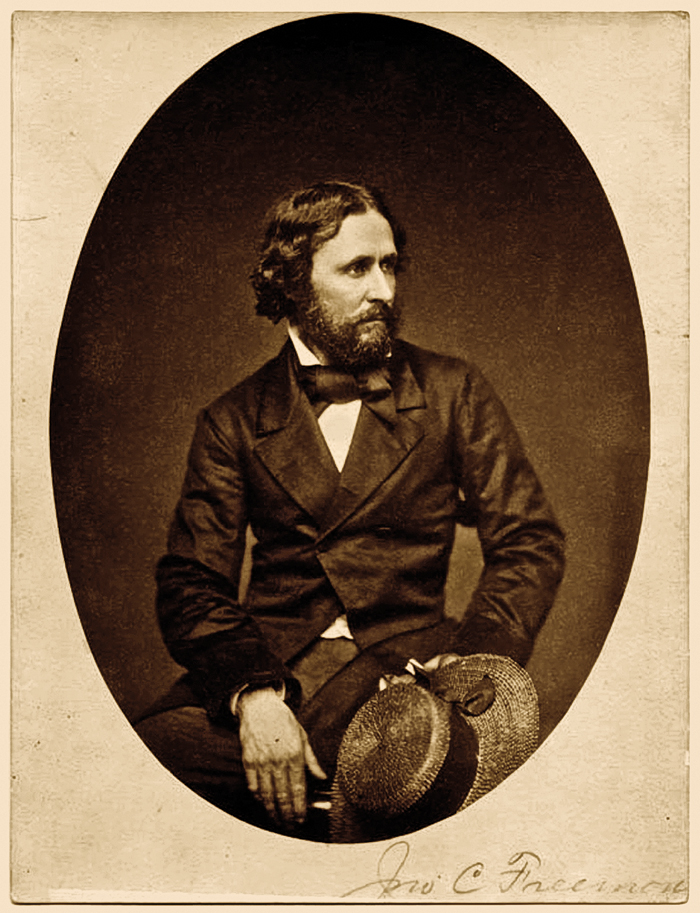

By 1848, John C. Frémont was a national hero. He had led three expeditions into the Great American Desert, and his maps opened the frontier West to settlement. His explorations to South Pass, Great Salt Lake, the Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin and many other places stirred the imaginations of Americans.

Missouri Sen. Thomas Hart Benton promoted railroad expansion in the West, favoring a route from St. Louis, Missouri, to San Francisco, California Territory, following the 38th parallel. Frémont, married to the senator’s daughter, used his celebrity to secure funds for a fourth expedition to scout that route.

On October 3, 1848, Frémont, his wife, Jessie, his infant son and 33 stalwarts sailed up the Missouri River. Members included artist Edward Kern and mapmaker Charles Preuss, as well as veterans of previous expeditions, three California Indians and a former slave.

The expedition bucked common wisdom by attempting to cross the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the late fall. It was an inauspicious start when Frémont’s infant son died before the group started riding west. The tragic loss seemed only to steel Frémont’s desire to continue.

Pressing up the Kansas River, the explorers were held up for days near modern-day Topeka, Kansas, by a prairie fire that members had accidently started. On November 3, while looking for the Arkansas River, snow-filled winds blew like a hurricane.

Near Chouteau Island, one mile south of the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, the expedition landed on the Santa Fe Trail. They reached the abandoned Mormon cabins at Winter Quarters in present-day Nebraska on November 21. At Fountain Creek, in present-day Colorado, they stopped at a pueblo, where they received unmistakable warnings not to cross through the mountains, given the early winter. Instead of heeding sage advice, Frémont convinced Old Bill Williams, a local trapper, to guide him through the mountains.

On December 3, the expedition passed through Mosca Pass at more than 9,000 feet and descended toward the San Luis Basin. Inches of fresh snow seemed to fall every day. By December 7, the temperatures were dropping below zero. The expedition made good time following the Rio Grande and supplemented their diet with elk meat.

They left the Rio Grande to ascend the mountains. The situation soon turned desperate. More than half the mules had died by December 20, and the expedition was having great difficulty moving men and equipment. The starving mules ate blankets, packs, ropes and each other’s manes and tails, and continued to perish. Their corpses marked the expedition’s path.

On December 22, as storms continued to pelt the surveyors, they had to admit defeat. Turning back, they tamped and dug a path through the snowdrifts. “The cold was extraordinary…the day sunshiney, with a moderate breeze,” Frémont later wrote his wife on January 27. “We pressed up towards the summit, the snow deepening, and in four or five days reached the naked ridges which lie above timbered country, and which form the dividing grounds between the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Along these naked ridges it storms nearly all winter, and the winds sweep across them with remorseless fury.”

The floundering expedition established Camp Hope, where they celebrated Christmas with a feast of mule meat. The next day, Frémont sent four stalwarts down the mountain to bring help from the Rio Grande settlements. The expedition fragmented into clusters as many as seven miles apart as the remaining men blindly felt their way toward safety, sometimes forced to ascend ridges when the path through canyons proved too difficult. On January 9, Raphael Proue was the first to die.

Near starvation himself, an emaciated Frémont waited for weeks before leading a second group to seek succor. This group fared well. After two days of walking, they luckily procured horses from an Indian camp. On January 16, they encountered three members of the first group, who had cannibalized their deceased companion to survive. Frémont soon was in Taos, New Mexico Territory, staying at Kit Carson’s home while he organized a rescue for the men left behind. On January 23, the rescue expedition under Alexis Godey set out.

For the men left on the Rio Grande, existence had become a frozen hell. Within two days of Frémont’s departure, the food ran out. The group splintered. Madness and despair were visitors to the sullen campfires. They, too, practiced cannibalism. On January 28, Godey’s rescue party arrived. By then, 10 members had died.

Frémont was not among the rescuers. He was organizing the next leg of his survey to the new state of California, bypassing the deadly mountains. In 1853, Frémont and a new outfit set out for California. Despite the Pathfinder’s fourth expedition coming to ruin, many members maintained a favorable impression of their leader.

History was not done with Frémont, a man who had a fifth expedition, a failed run for the U.S. presidency and a lackluster Civil War career in his future.

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.