Tomasita Duran could not believe what was right before her eyes. On that day in 2004, the director of the housing authority saw something special about her hometown—one of the oldest native pueblos in the United States, the 800-year-old village then known as San Juan Pueblo.

Tomasita Duran could not believe what was right before her eyes. On that day in 2004, the director of the housing authority saw something special about her hometown—one of the oldest native pueblos in the United States, the 800-year-old village then known as San Juan Pueblo.

“I’m looking around,” she says, “and I realized, ‘Oh my God, this is the next project.’”

Little did she know that over the next dozen years, she would strengthen the cultural bond of the Tewa community, leverage small state and federal grants into a $9 million project and rewrite the rules on historic preservation in New Mexico.

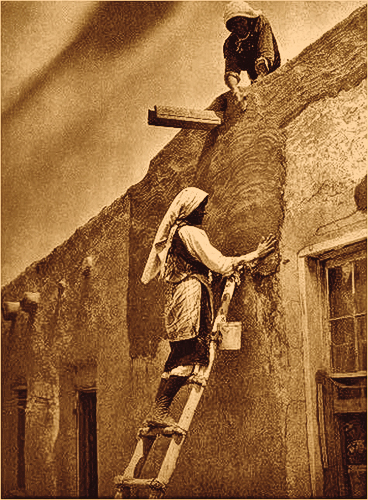

What Duran saw that day was an original settlement in total disarray. Where once 200 adobe homes had existed in the pueblo’s four plazas, only 56 remained.

“Many of the homes had been abandoned, all had deteriorated, some had already been destroyed,” she says. “Every home had multiple owners. Over the years, the parents gave the living room to a daughter, the bedroom to a son—so every home had a complicated ownership.”

When she first approached the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Council about restoring the pueblo—“our most sacred area”—she received discouragement. “Several council members said this was impossible and I was dreaming,” she says.

Duran was not dissuaded. She received a $7,500 state preservation grant and hired high school students from the pueblo to map the plazas. She put together 15 groups of residents to plan the restoration, asked six cultural advisers to examine unearthed artifacts—from human remains to pottery—and worked with state officials to rewrite the rules on historic preservation to account for cultural values.

“Normally you preserve something to a specific time in the past, but these homes had no kitchens, no baths, so they were unlivable if we restored them to their original design,” she says. “Our tribal council said this wasn’t being preserved for yesterday, but for tomorrow. The state said, ‘Wow, nobody’s ever looked at it like that before.’”

– Courtesy Ohkay Owingeh Housing Authority –

Today, 34 homes are occupied and plans are underway to restore 15 more. The homes have been modernized and second stories added to provide bedrooms. “This is not a museum, but a living place,” she says.

Everyone is astonished at how Duran leveraged small grants into a $9 million restoration. “It is one of the most successful grants in historic preservation history because it was leveraged,” says Tom Drake, public relations director for the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division.

For Duran, the success was closer to home. “This has been a revival of our culture,”

she says, noting that the community has participated in more traditional dances

and feast days.

Inspired by this community project that has turned the pueblo into livable homes, the council renamed the pueblo its pre-Spanish name—Ohkay Owingeh. In Tewa, the name means “place of the strong people.”

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.