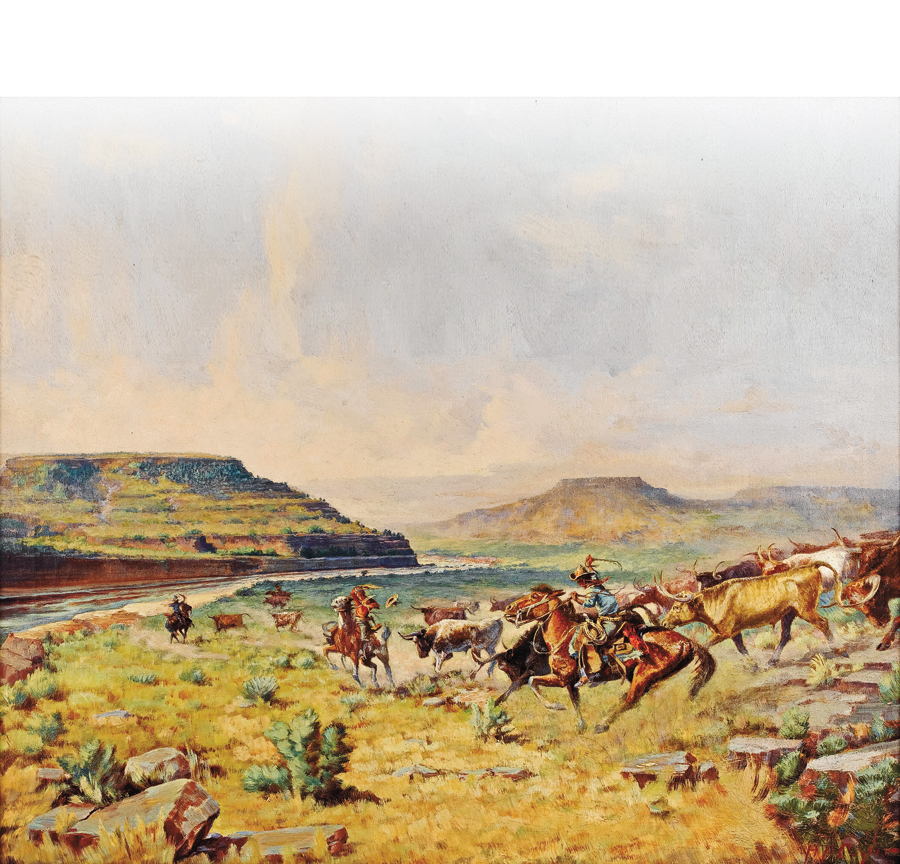

To the uninitiated in the Old West, the ranching business centered on cattle, but in reality, the livestock trade focused on grass and water, so much so that droughts always threatened the success of the Cattle Kingdom.

Without regular rainfall, grass withered away, cattle fell to hunger or thirst and ranchers faced a domino effect of ever-increasing consequences that were measured in years rather than months. Ironically, the Cattle Kingdom that evolved after the Civil War overlapped the semi-arid reaches of the Great Plains, a region located between the Rocky Mountains and the 98th Meridian near Fort Worth, Texas, and a region where tenuous rain made for uncertain ranching.

From Fort Worth west to the Rockies, annual rainfall averaged less than 20 inches, a yearly accumulation that kept the cattle business on edge. The ranches in West Texas, the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles, southwestern Kansas and southeastern Colorado stood at greatest risk because of higher evaporation rates. In those areas, temperatures and altitudes resulted in evaporation rates ranging from 52 to 60 inches during the critical months of April through September. By comparison, evaporation rates farther north in Dakota Territory ranged from 30 to 38 inches during the same months.

Because of the lower evaporation rate, northern ranches had a higher effective yield on rainfall during the hot months than Texas ranches that included the XIT, the Matador, the Spade and the Spur. As South Plains historian William Curry Holden put it, “From the earliest days of its settlement West Texas has had a reputation for frequent dry spells, and, at longer intervals, severe droughts.”

While the large corporate ranches often had the resources and flexibility to endure drought, the smaller outfits did not. For instance, one modest rancher six miles north of Colorado City, Texas, started the spring of 1885 with a herd of 1,500, but rain failed to fall until August and then only in modest amounts. By that time, his herd had dwindled to 11 animals. At the market price of $35 a head that summer, the rancher’s economic loss totaled $52,115 (equal to $1.3 million today).

A nearby rancher, F.G. Oxsheer of the Jumbo Cattle Company, fared better. He managed to save half of his modest herd and skinned the carcasses of the others to sell the hides at $3 apiece.

The Big Dry

The year 1885 started one of two major multi-year droughts that shook the West Texas cattle industry and forced ranchers to reassess their practices, just to survive. Those droughts came within a 10-year period, first in 1885-87 and then in 1890-94, though the span of greatest difficulty varied slightly by locality. The three-million-acre XIT ranch, for instance, stretched 200 miles along the western border of the Texas Panhandle so some XIT divisions fared better than others during a drought, thanks to localized showers.

The severity of both droughts varied by region. The 1885-87 shortfall was labeled the “Big Dry” in the Pecos River region of far West Texas, while the 1890-94 deficit on the South Plains was called the “worst drought ever experienced before or since” by Murdo Mackenzie, manager of the Matador.

Regardless of a drought’s timing, the impact on cattle and the implications for ranchers were the same, death for the former and bankruptcy for the latter. First, the grass withered away. Then the streams and waterholes dried up. Next, cattle in ever weakening condition had to walk farther away from water to find nourishment before returning to dwindling water resources. Then the cattle died, either from thirst, starvation or exhaustion. Cows with suckling calves and weaned calves, steer yearlings and bulls succumbed first. Dry cows and grown steers survived best.

Sometimes during drought, cowboys killed weaning calves so that their mothers might survive since their wombs were the wellspring of ranching prosperity by producing the annual calf crop. On the Spur Ranch, the 1892 calf crop dropped 32 percent from the 1891 crop of 11,000 due to drought-induced miscarriages. Smaller ranches had an even harder time, such as Borden County’s MK Ranch, which branded 6,000 calves in 1893, but only 160 calves a year later, bankrupting the 25-square-mile ranch.

Martha Jane Conway, a cattleman’s wife living near the Spade Ranch, recalled the drought desperation of 1892, stating, “There was but little grass for the cattle. We dug bear grass, chopped up the roots and fed them to the cows. We also fed them prickly pear, after burning off the stickers, and cut limbs from hackberry trees and fed them to the cattle.”

Important as feed was, cattle could go days without grass, but not nearly that long without water. During the hot summer months, cattle consumed on average about 15 gallons daily. On the Spur Ranch, this translated into a daily need of 750,000 gallons for an average herd of 50,000 head.

Desperate for precipitation, ranchers explored different options, some scientific and some less so.

The Gods of Science

Fred Horsbrugh, manager of the Spur, asked his bookkeeper, S.G. Flook, to write “Hester’s Weather Forecasts” for a scientific assessment of rain probability, sending along a $3 subscription fee, plus the ranch’s latitude, longitude and altitude. Hester may refer to New Orleans cotton statistician Henry G. Hester, whose reports documented rainfall in Texas and other areas. The reply came back that the “horoscope showed no relief from present conditions for some time to come.” The forecast proved correct, even if unscientific.

More scientific than a horoscope, though, were the rainmaking experiments partially funded by the federal government in Midland County in 1891. Based on the fact that rain often followed major Civil War battles back East, scientists theorized that concussions wrung rain from clouds.

Weather theorists shot off cannons and dynamited clouds on a rain-starved Midland County ranch with mixed results. Though some rain did fall, various accounts were contradictory about how much. Even so, nothing proved a connection between the sky blasts and any ensuing rainfall.

The larger spreads relied on more conventional and less noisy methods of securing water. First, ranchers dammed up small creeks and draws to capture runoff in earthen tanks. Second, they drilled wells and installed windmills to tap underground aquifers.

By 1900, the XIT, for instance, had built 100 dams and installed 335 windmills, enough to provide water for more than 150,000 head of cattle. The estimated cost of a half-million dollars was cheap compared to the price of no rain.

To deal with grass shortages, ranchers improved their range management techniques, avoiding overgrazing and providing cattle with supplemental feed, either grown by their expanding agricultural operations or by neighboring farmers.

Lessons Learned

In the end, although the 19th-century droughts in West Texas and the Great Plains threatened ranching as an enterprise, they also ensured ranching’s survival by forcing adaptations to the lack of consistent rain. Even today, in spite of improved rangeland and water conservation techniques, West Texas and the Great Plains still must periodically face the impact of its semi-arid climate, demonstrated as recently as the 2014-15 Texas drought.

When the drought of 1885-87 broke in San Angelo in April 1887, San Angelo Standard Editor J.G. Murphy wrote, “The sweetest strains of melody that have fallen on the ear of many a stockman in this country for many a day were caused by the patter of raindrops on Tuesday night.”

Elsewhere in his column that day, Murphy made a statement of hope: “It’s going to rain some more.”

To this very day, that 1887 wish remains the enduring hope of West Texas and the Great Plains.

Preston Lewis is a fellow and past president of the West Texas Historical Association and a Spur Award-winning author of “Bluster’s Last Stand,” published in True West.