– Courtesy The Brinton Museum –

The time: November 1918 to January 1919 during the Spanish influenza pandemic. The place: Great Falls, Montana. The artist: Charles M. Russell. The cost: An estimated 675,000 American lives and at least 50 million across the world.

Today, COVID-19 has put the American West art world in a new nightmare.

The pandemic has gotten so bad, the board of health orders “Theaters, churches, schools, dance halls, pool halls and card rooms” closed. “Public gatherings are also prohibited.” Two months later, a local artist (in need of an editor) writes a friend:

“… this old sickness surlenly trimmed this camp hers prufe enough I just sold a picture to an undertaker”

The time: November 1918 to January 1919 during the Spanish influenza pandemic. The place: Great Falls, Montana. The artist: Charles M. Russell. The cost: An estimated 675,000 American lives and at least 50 million across the world.

Today, COVID-19 has put the American West art world in a new nightmare.

Western art galleries have focused on online marketing, but selling art online is difficult.

“There is a generation gap opening up between younger collectors, who are more comfortable purchasing art online and our older clientele, who are not,” says Maria Hajic, director of the Department of Naturalism and Contemporary Western Art at Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “It is the latter group that has supported and sustained the Western art market for decades. …I still believe the art business is about personal connections, but that is changing.”

– Courtesy Sherry Blanchard Stuart –

Western artist Robert Pace Kidd, who splits his time between California and Mexico, headed to the Baja coast in February ahead of pandemic-forced safety measures. “I’ve been busy making art,” he says. “Selling’s a whole different matter.”

“I don’t know if anything’s going to pick back up until there’s a true vaccine,” Comanche artist Nocona Burgess says.

Laura Foster, director/curator of the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, New York, flew to Spain in February to care for her sick mother. By the time her mother was well enough to travel, coronavirus-stricken Spain had rigorously locked down. Foster, interviewed by telephone in June, hoped to return to the museum by July. “When I left, I was the only person abandoning their physical location for non-COVID reasons,” she says, “and then everyone else joined me with the physical distancing.”

Even those writing about art have been hit. “The closing of museums and libraries during the current pandemic has certainly slowed research on Western art,” says B. Byron Price, director of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma, who provided this article’s Spanish flu information regarding Great Falls and Russell.

When this pandemic ends remains uncertain—as does what the post-COVID Western art world will be.

“Unfortunately, there may be a thinning out of galleries, some museums and even publications if the COVID pandemic persists longer than early 2021,” says Mark Sublette, president of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona.

Art museums must also figure out what to do with scheduled exhibits that never opened, or were rarely seen, because of COVID-19 restrictions. Will exhibits be rescheduled? Canceled? The Frederic Remington Art Museum loaned art for “Natural Forces: Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington,” which was scheduled to open at the Denver Art Museum in March and travel to the Portland (Maine) Museum of Art and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. “We expect to announce that we are extending the loan to allow the tour to continue,” Foster says, then adds: “Nothing really can be answered until the pandemic ends.”

Online presences will be a must, insiders predict, for post-pandemic galleries, museums and artists.

“The days of merely waiting for clients to walk through the door to make a sale have seen their heyday,” Sublette says. “There is no turning back the clock. The time is now.”

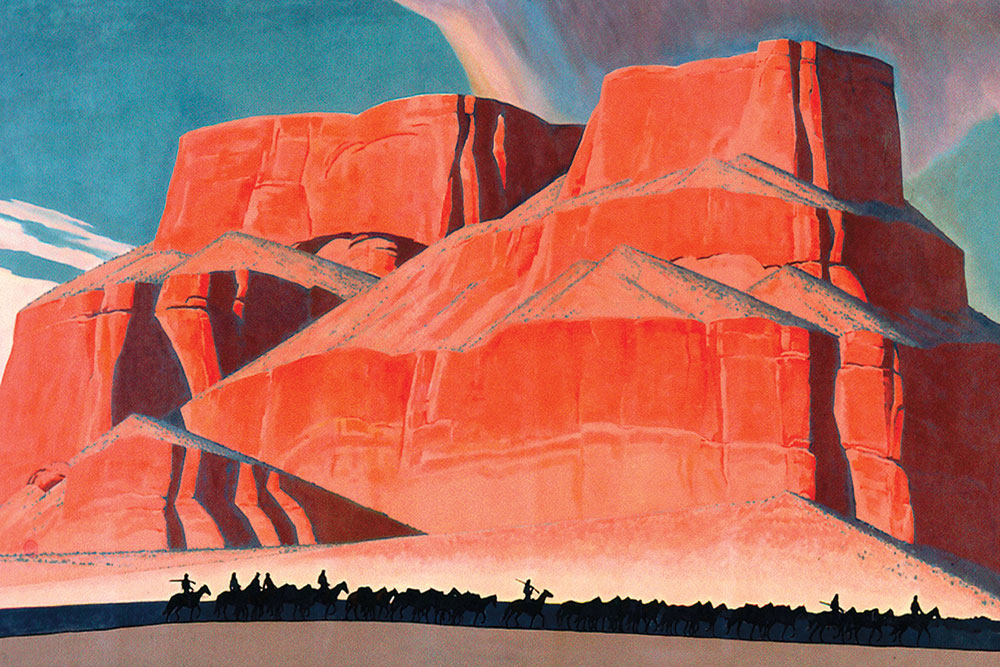

Just like it was in 1918-1919. When the Spanish flu and World War I forced the Great Northern Railroad to withdraw a $5,800 commission, artist Maynard Dixon told friend Charles Lummis that he wasn’t certain he’d keep painting.

“Dixon was deeply depressed,” says Sublette, author of Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along the Distant Mesa. “Lummis wrote Dixon back with words of encouragement, and Dixon was able to move forward. He did the illustrations for that year’s Bohemian Grove, which I’m sure gave him great solace. …The takeaway is Dixon’s painting career improved dramatically soon after the pandemic resolved, and he painted some of his best paintings over the next 20 years.

“Hopefully, we as a country can look back at Dixon’s ordeal and realize we, too, will have better days again.”

Long before COVID, Burgess reminds us, Comanches and other Indian tribes dealt with smallpox pandemics. “At first, the treatment was to sweat it out in a sweat lodge and then jump into cold water––absolutely the worst thing you could do.” Eventually, the Comanches and other tribes learned the best preventative. “Social distancing,” Burgess says. “They built separate camps for the sick.” A form of art came from smallpox, too. “Those red dresses you see decorated with white shells,” he says, “were worn by smallpox survivors.”

Kidd believes that just as Western artists came through the Spanish flu, World War I, the Great Depression and other wars, disasters and outbreaks, today’s Western artists will do the same.

“Artists,” he says, “seem to find a way.”

A Thousand Texas Longhorns, a novel by Johnny D. Boggs about Nelson Story’s 1866 cattle drive to Montana, is being published by Pinnacle this year.