— Wells photo Courtesy Brad Courtney; other images courtesy Sharlot Hall Museum unless otherwise noted —

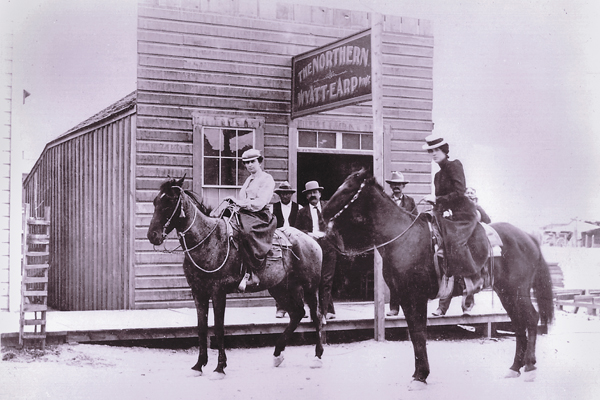

Tombstone boasts Arizona’s most famous gunfight, but Prescott can claim its most famous saloon story. It speaks of a baby won in a gambling game after being abandoned on the bar of a prominent saloon on Whiskey Row, Prescott’s famous collection of watering holes located in the center of its business district.

The baby dumping took place during January 17-28, 1898, but the name of the eight-month-old baby and the bar she was left in was known one way locally and another way popularly. The local tale mysteriously disappeared from print and passed into the realm of oral history.

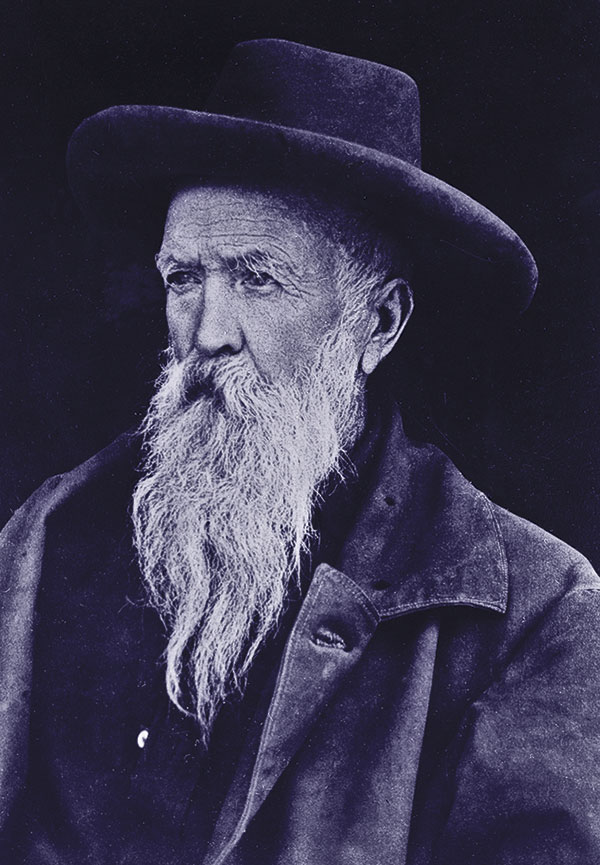

Then, 29 years later, an original Prescottonian, Edmund Wells, published the story in his memoirs, Argonaut Tales.

A Dicey Game

In a classic combination of frontier history and folklore, Wells, one of the most respected and accomplished figures in Arizona history, recalled within the three-chaptered section titled “Chance Cobweb Hall” the story of a baby girl given to a Chinese man, George Ah Fat, to watch until the mother straightened out her personal affairs.

After several days, Ah Fat realized the mother was not going to return. He had to do something about this tot. He waited until a snowy evening, when a larger-than-usual crowd had been driven into Cobwell Hall, a prestigious Whiskey Row saloon owned by former Colorado River steamboat captain P.M. Fisher. That night, Ah Fat surreptitiously placed the baby on the bar and blended into the crowd.

When saloon patrons discovered the baby—said to be beautiful—they concluded she had been abandoned. Heated arguments commenced regarding the baby’s immediate and future welfare.

Before the situation became precarious, Fisher interjected a proposal: all desirous of adopting the child should partake in a game of dice—$10 for one throw of four dice for the pretty stranger. None dissented.

Player after player rolled until Robert Groom, Prescott’s original surveyor, rolled four fives, surely the winning roll. Yet Judge Charles Hall stepped out of the shadows and, taking the last roll, beat him by miraculously throwing four sixes.

Groom suspected cheating, but could not prove it. Hall had won the baby. Groom, however, demanded the honor of naming the coveted waif. A lengthy, poetic christening followed; the child would be called Chance Cobweb Hall.

After a giddy champagne toast, Hall took the baby home. He and his wife adopted the little lady. Wells wrote it was then “forgotten as one of the romances of the town.”

A Chance Reunion

Twenty-five years later, Wells was in San Francisco, California, attending a benefit dinner for “dependent girls” and found himself sitting across from a couple, the female member of which was especially attractive and strangely familiar.

Wells overheard them mention a town called Prescott. After he questioned the charming lady, she divulged she was born and raised there. Her name? C.C. Hall; short for Chance Cobweb Hall.

How she received her unusual name, she didn’t know: “I suppose that some kind of Western romance was connected to it. Perhaps I will know sometime.”

Such was the only full-length version of these events for more than seven decades. It was often accepted as historical verity. Recent research, however, has revealed several mistruths, perhaps intentionally supplied by Wells.

At least two of the characters in Wells’s narrative were dead, including Fisher. Groom was 73 years old at the time and surely not interested in adopting a baby. And the cherub did not need to be named because she already had a name: Violet Bell.

The True Saga Unfolds

The true saga of Violet “Baby Bell” Hicks began on January 17, 1898. The baby was abandoned on a snowy evening, not in Cobweb Hall, but in the Cabinet Saloon.

The Cabinet had served as the heartbeat of Whiskey Row for more than 20 years. Activities were in full swing when a “rather comely young woman” walked through the bat-winged doors, holding a swaddled baby.

The heavily veiled beauty was probably the baby’s mother, Mary Bell. She deposited the baby on the bar and disappeared down Whiskey Row. An attached note stated this baby was being abandoned and was now homeless. It also identified the father: William Bell.

At a time when saloon stories usually featured drunken men pulling pistols and shooting at each other, this one rang different. A local rag recounted that a “surging mass of brawny men crowded up to get a sight of the little one.”

No less than 40 were so taken with the infant—and undoubtedly inflicted with a benevolence supercharged by whiskey—that they each volunteered to give her a home. A few married, but childless, men were ready to fisticuff for the tiny trophy.

Did someone, as Wells asserted, step in and propose that the right to adopt the abandoned child should be won in a gambling game? Prescott newspapers never mentioned the gambling, yet the likelihood that they gambled for the cherub is high.

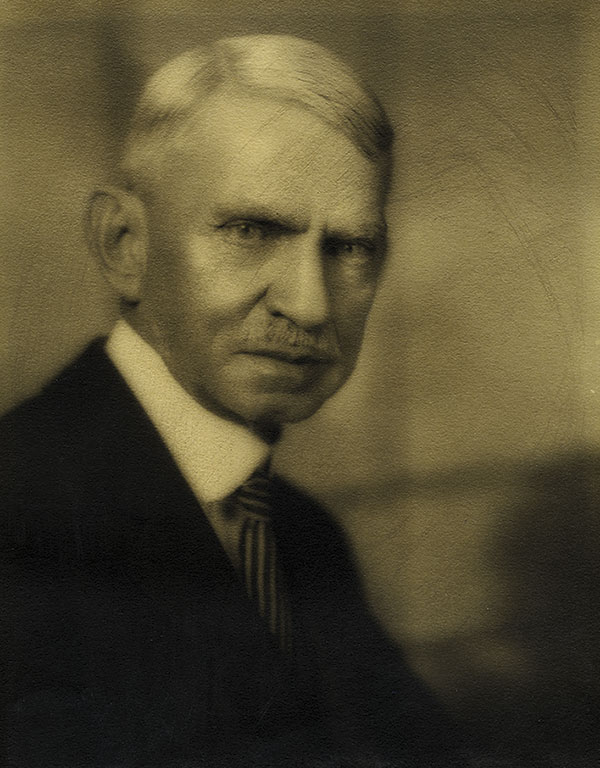

Charles Hicks, probate judge of Yavapai County, entered the scene. He had been summoned because, during this time in territorial history, probate judges handled all adoptions.

The judge did not win the baby by rolling four sixes in a dice game. He simply “decided the question by announcing that he would take it himself.”

Outside reports noted that Judge Hicks left the Cabinet with $300 “for the child’s benefit,” given by the “unsuccessful men.” Chances are that at least 30 men were in the process of gambling for the child when the judge walked in and snatched the baby. In an act of charity, these men offered up the ante to jumpstart the baby’s care.

On January 26, Charles’s wife, Allie, petitioned her own husband to adopt Violet Bell. Two days later, Baby Bell became Violet Hicks.

Prescottonians were happy with this outcome. “Thus has the little waif of the Cabinet saloon fallen into a home good enough for any child, one in which she will receive that care, training and education which any parents would be proud to have a child receive,” the Prescott Courier noted.

The local story disappeared from print until Wells produced his Chance Cobweb Hall story in 1927, with its fairy tale ending.

More Tragic than Magic

Little is known about Violet’s childhood. She never knew her adopted mother, Allie, who died almost exactly two years after she adopted Violet. Violet told her children what she did remember: she had learned to ride a horse before she could walk and that the Hicks had employed a Chinese cook of whom she had been fond.

Violet’s adult life proved more tragic than magic. After moving to California, she married architect Arthur Binner and had four children. Arthur became an alcoholic. Divorce followed in 1929.

Charles, in an act of deep and abiding fatherly love, traveled to California to help his daughter during this trying time. Upon returning home, he fell ill and passed away on Christmas Eve.

Violet became a gambling addict and neglectful of her children. At one point, she trekked all the way to Alaska to find her biological father, only to be told he wanted nothing to do with her.

In 1972, rumors circulated that C.C. Hall, under an assumed name, was living near Whiskey Row. Violet Binner, however, had died of a heart attack two years earlier, on October 12, in Redwood City, California. She was 72 years old.

Why so many discrepancies between Wells’s Chance Cobweb Hall account and the true story of Violet “Baby Bell” Hicks? Was Wells, friend to Judge Hicks, aiming to protect Violet by changing the names and facts? Did the Hicks never reveal to her the somewhat shameful way she came to be adopted? Did all of Prescott follow suit?

The answers to these questions about Prescott’s famous baby on the bar are probably “yes,” but we will never know.

Brad Courtney lives in Prescott, Arizona, and is the author of Prescott’s Original Whiskey Row. A former Colorado River boat pilot and sheriff of the Prescott Corral of Westerners International, he also served on the editorial board of Arizona’s now-defunct Territorial Times.