The audacious outlaw fought and raided his rival renegades without retribution.

All images courtesy True West Archives unless otherwise noted

Their war-cries were enough to jolt even some of the most hardened of men. When you first saw them, they had likely been watching you for quite some time. They could seem to appear from nowhere and dissolve back into the surrounding rugged landscape just as quickly. When attacking their enemies with a ruthless ferocity, their presence was often greeted with a familiar panicked cry heard throughout the Southwest: “Apaches!” And with a party of such menacing warriors having set upon them, young Billy Bonney and friend Tom O’Keefe were in serious trouble.

Billy and Tom had made the mistake of travelling through the northern Guadalupe Mountains in New Mexico Territory in the fall of 1877. After filling their canteens in a stream, Billy had started to make his way back to O’Keefe and their horses when the Apaches had sprung upon them, seizing a chance to kill or capture some trespassing White Eyes. After waving O’Keefe to ride out of the ambush, Billy, or “Kid Antrim,” as he was also known, quickly found a place to hide. He remained hidden until making his way downstream after nightfall. It must have been a tense journey, with the Apaches potentially reappearing at a moment’s notice. The slender teenager survived the night and at dawn began walking an easterly course.

For the next three days, Billy wearily walked during the night and slept during the day. His feet became increasingly raw, swollen and blistered due to wearing boots that were too small for him without socks. After finally catching sight of a house in Seven Rivers, he approached and was greeted by the barrel of a Winchester rifle held by Barbara Culp Jones. Realizing the exhausted bucktoothed boy stumbling in the darkness was no threat to her, “Ma’am Jones,” as she was widely known, helped him inside and tended to his ghastly feet. After making him drink some warm goat’s milk, Ma’am Jones promptly put him into bed with her own sons. As he closed his blue eyes that night, young Billy Bonney could count his blessings for still drawing breath. He was fortunate not to have been killed back in those mountains and even more fortunate not to have been taken alive.

Life Among the Apaches

William H. Bonney would have certainly become aware of the Apaches when arriving in New Mexico Territory as a young boy named Henry McCarty along with mother, Catherine McCarty, stepfather, William Antrim, and brother, Joseph, sometime in late 1872 or early 1873. Living in Silver City for over two years, he likely heard stories of the Apaches’ raids, kidnappings and torturous treatment of captives throughout the region. As a teenaged boy, Henry quickly learned to be wary of the Apaches. To the Apaches, white arrivals like Henry and his family were a trespassing and damaging threat to their way of life. The Apaches felt wholly justified in waging war against the White Eyes, who had been increasingly encroaching on their land for years, bringing bluecoat soldiers and diseases with them.

The most prevalent Apache tribe in New Mexico Territory was the Mescaleros. After decades of fighting Comanches, the Spanish and White Eyes, the majority of them settled onto the Mescalero reservation, established on May 27, 1873, by order of President Ulysses S. Grant. At the reservation located near Fort Stanton (Zhúuníidu to the Mescaleros), and at the other Apache reservations throughout the Southwest, hardship, destitution and diseases were commonplace.

It is uncertain if surviving the ambush in the Guadalupe Mountains in the fall of 1877 was the Kid’s first experience with Apaches. A note written on a cigarette paper found inside a metal cartridge shell which had been lodged inside a crevice in a cave in the Florida Mountains suggests it may not have been the only encounter he survived. Sometimes referred to as “the last stand note,” it reads:

“this is our last shell and about 10 Indians left so our chances look slim. But we are going to take a chanch [sic] yours truly, Wm. Bonney.”

If it’s authentic—and the handwriting (especially the signature) do look strikingly similar to confirmed letters written in the Kid’s hand—it remains unclear when this standoff took place or who Billy’s companions were at the time. What is certain is that the Kid’s “chanch” paid off and he lived to survive another day.

The Apaches and the New Mexicans

The Hispanos of New Mexico Territory, the people the Kid would immerse himself amongst, largely despised the Apaches for their bloody raids and kidnappings. The Apaches naturally resented the Hispanic presence in what had for so long been their homeland, as well as the brutality they had suffered at the hands of Spanish and Mexican soldiers. A fearsome Bedonkohe Chiricahua warrior named Goyaałé (Goyahkla), better known as Geronimo, harbored a particular hatred and contempt for Méxicanos. As the Kid had found himself caught up in a clash between the British and Irish during the onset of the Lincoln County War, he also found himself amidst another clash of cultures with the Hispanos having effectively become his people.

Courtesy Museum of New Mexico

Pedro M. Rodriguez, the grandson of Lincoln County War participant Fernando Herrera, told a story that had passed down through the family and was likely embellished as a result. According to Pedro, his grandfather Fernando Herrera had been living in Ruidoso at the time and owned around 400 head of cattle, grazing them in Turkey Canyon. Mescaleros had taken to butchering some of the livestock. Herrera, whose daughters Manuela and María Antonia Miguela had married Billy Bonney’s fellow Regulators Charlie Bowdre and Josiah ‘Doc’ Scurlock, gathered up a posse which included the Kid. According to Rodriguez:

“They started out early one morning for Turkey Canyon. When they got to Turkey Spring about half way up the Canyon, they met Chief Kamisa and about twenty-five Indians. Kamisa was Chief of the Mescalero Apache Indians. While the posse was talking to Chief Kamisa the Indians formed a circle around the men and told Kamisa to tell them they were going to kill every one of them. Billy the Kid told the men in Spanish, to get off their horses and tighten up their front cinches and follow him. Billy mounted his horse with a six gun in each hand, and started hollering and shooting as he rode toward the Indians. The rest of the men followed, shooting as they went. They broke through the line of Indians and not a one of the men were hurt. They gathered a few head of cattle and took them home and put them in a corral.”

Fernando Herrera and Kamisa, who would have been a Mescalero sub-chief at best, apparently became friends soon after. Pedro M. Rodriguez, who was six years old when the Kid was killed, recalled often enjoying talking to the Mescalero leader while growing up.

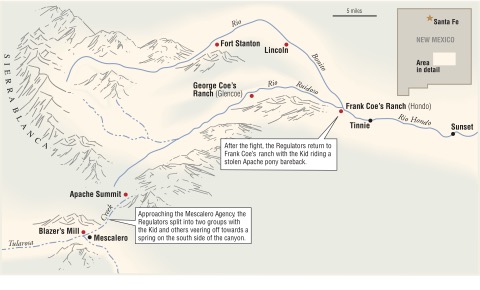

Rustling Apache Horses

Both Billy Bonney and Fernando Herrera participated in rustling stock from the Mescalero Agency on August 5, 1878. In need of horses after coming out the worst of the infamous five-day siege in Lincoln which served as the climax of the Lincoln County War, the remaining Regulators and a handful of their Hispano allies made their way to the agency expecting little resistance. The Kid and the Regulators had stopped to take a drink from a spring when gunshots rang out ahead of them, startling Billy’s horse and causing it to bolt. Fernando Herrera and his fellow Hispanos had ridden on farther down the road and encountered some armed Apaches. Agent Frederick C. Godfroy and his somewhat shady clerk Morris J. Bernstein quickly mounted up and galloped toward the shooting to investigate. Bernstein was shot dead amidst the fray, presumably by Atanacio Martínez after the clerk had fired shots in his direction. Despite not being in the vicinity, the Kid would be wrongly credited with Bernstein’s death for decades.

Agent Godfroy raced back toward the agency before several soldiers provided support. Along with the group of Apaches, they proceeded to open fire on Billy and the Regulators at the spring. Regulator George Coe quickly mounted his horse, with the Kid climbing up behind him, and they soon made their way to the Agency corral after surviving a hail of gunfire. The Regulators promptly opened the gate, and the Kid rode bareback on an Apache pony as they made off with all the Agency’s stock.

Photo by Dana P. Chase, Courtesy Lynda A. Sánchez

The chaos at the Agency that day might not have been the only time the Kid helped himself to horses on the reservation. Apolonio Sedillo, whose family the Kid supposedly stayed with for a time in San Patricio, recalled once accompanying Billy in stealing horses and mules from the Mescaleros living peacefully near Fort Stanton. One particular mule (or possibly a horse) was tethered by a rope which was tied off inside a tepee. A small dog’s barking prevented them from getting close enough to steal it, until Billy came up with the idea of continually throwing sopaipillas (fried bread), which he kept in his saddlebag. This kept the dog quiet enough for them to sneak up and cut the rope in order to snatch the presumably prized animal under cover of darkness. As Sedillo recalled it, after making off with the stolen stock, they laid low in Ratón Springs before eventually driving the stolen ponies to John Chisum’s ranch.

While the Kid became a heroic symbol of resistance against the Santa Fe Ring and Anglo expansion to many Hispanos, to the Apaches he was nothing more than a pest. Successfully stealing horses from the most notoriously skilled horse-thieves in the territory perhaps appealed to the Kid’s roguish sense of humor. The Mescaleros, however, were understandably not laughing. The last thing they needed on the reservation at the time was a little White Eye snatching their ponies. As a people, they had lost enough already.

The Renegade and The Kid

In terms of celebrity, 1880 in New Mexico Territory was the year of Victorio and Billy the Kid. A frequent reader of newspapers, the Kid would have known all about “Victorio’s War,” or at least what was reported. After jumping the Mescalero reservation on August 21, 1879, Victorio and a band of followers, including his mystical woman-warrior sister Lozen and the esteemed warrior-chief Nana, blazed a path of armed resistance across the southwest. Dozens of Whites, Hispano New Mexicans and Méxicanos met their deaths as a result of Victorio’s continued defiance in various raids and skirmishes. The May 6,1880, Las Vegas Daily Gazette described the Chihenne Chiricahua Apache war chief’s resistance as such:

“Victorio is still striking at the peace and prosperity of Southern New Mexico. This is the most remarkable and destructive Indian war, considering the number of Indians, yet recorded in the annals of the country. Somebody has blundered. It is likely that there is not enough troops in the Territory to surround and capture Victorio. He moves with celerity from place to place, killing defenseless people in his road. The troops follow after. When overtaken, he is always found holding a strong position. He kills people, loses few men himself, is fierce in battle, cautious in retreat, wears his opponents out. The Mexican troops whipped Victorio, but on this side of the line he is the “boss.” It is time for the citizens to take Victorio in hand and destroy him with or without the permission of the government.”

Easier said than done. Neither citizens or the U.S. Army were able to capture or kill the elusive Apache leader. Victorio and many of his followers were eventually cornered by a large contingent of Mexican militia led by Col. Joaquin Terrazas at Tres Castillos in Chihuahua, Mexico, on October 14. The Apache leader and his companions put up a fierce resistance but were eventually overwhelmed the following day. Defiant until the end, after running out of ammunition, rather than allowing the Méxicanos the glory of his killing or capture, Victorio ended his own life by drawing his knife and plunging it into his own heart.

How Billy Bonney (left) and his comrades came up with their name is unknown, but there are clues. The moniker “Regulator,” which means “to bring under the control of law or constituted authority” was used as early as the Revolutionary War and enjoyed scattered usage during the Civil War. In 1878, the popular fictional character Deadwood Dick, often in the role of a “regulator,” was tearing across the pulp tundra, defending communities against evil outsiders. Since the Kid was an avid reader of dime novels, some surmise it may have been Billy himself who christened the Regulators.

In the wake of Victorio’s death, “Billy the Kid,” as he was christened by the newspapers, occupied much of the territorial press and his exploits were often embellished. The young outlaw and the Chihenne Apache leader had both rebelled against establishments and what they considered grave injustices—the Kid against the Santa Fe Ring, Victorio against the U.S. government. Both became notorious in their lifetimes and legends posthumously; standard-bearers of a desperate time in a harsh land. Simply sharing notoriety in the same territory naturally didn’t necessitate either man ever giving a damn about the other. The day the Kid arrived in Santa Fe in the custody of Pat Garrett on December 27, 1880, the Las Vegas Daily Optic reported that when told of having “a reputation second only to that of Victorio,” Billy could only laugh in amusement. Victorio on the other hand, had likely never even heard of Billy “the Kid” Bonney and would have been absent a reason to care if he had.

After making his famous jailbreak in Lincoln on April 28,1881, the Kid met his own end through the roar of a nervous Pat Garrett’s revolver in the darkness of Pete Maxwell’s bedroom in Fort Sumner on the night of July 14, 1881. Billy’s body had barely been laid to rest before tall tales, embellishments and outright lies began to surface about his activities. One particularly amusing tale was the Kid single-handedly managing to gun down five Apaches for refusing to sell him a horse. Another fabricated story featured Billy killing three Apaches and running off a fourth in order to save a rancher’s wife from being gang-raped. Yet another was the tale of his gunning down three Chiricahua Apaches in order to obtain their blankets and pelts during his time in Arizona Territory prior to his arrival in Lincoln County in October 1877.

While these tales firmly reside in the mythology that developed around William H. Bonney in the decades following his death, they are a testament to even the Apache people not being immune to the engulfing legend of “Billy the Kid.”

Suggested further reading: The West of Billy The Kid by Frederick Nolan, The Apache Wars by Paul Andrew Hutton, Apache Legends & Lore of Southern New Mexico: From the Sacred Mountain by Lynda Sánchez.

James B. Mills is a historian and published writer.

He dedicates this article to Lynda A. Sánchez. He resides in Australia and has spent much of his life researching the American West. His biography, Billy the Kid: El Bandido Simpático, will be published in 2022.