Scholars uncover answers and create more questions on the outlaw’s life and family from New York to New Mexico.

This past year has been a watershed in terms of new scholarship on Billy the Kid. Here, in a True West exclusive, are the new finds you need to know about.

—Bob Boze Bell

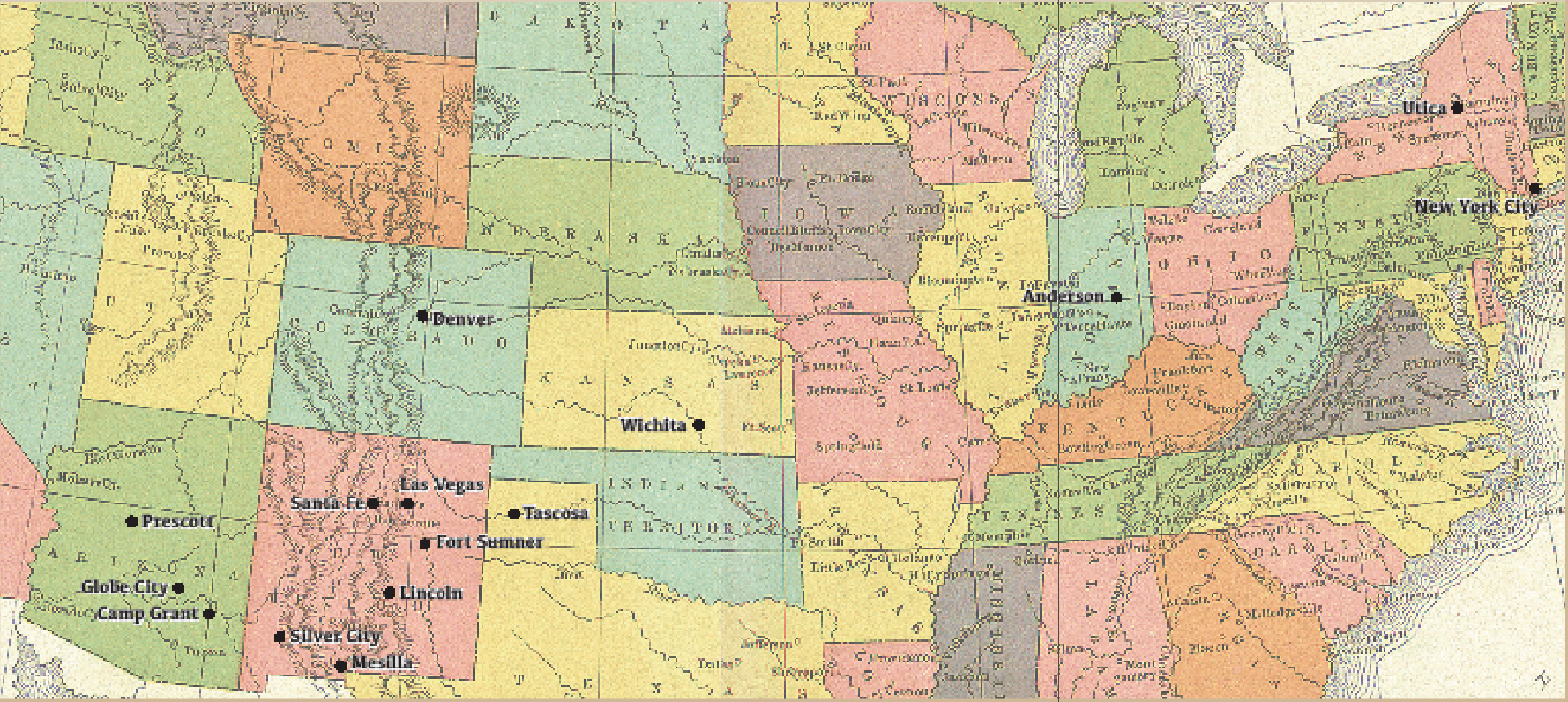

A map of all the main stops in the kid’s short life.

Was Billy’s Mother a Five Points Prostitute?

By Chuck Usmar III

–

When Catherine McCarty arrived in New York, her first work may have been in her aunt’s Bowery brothel.

Immigrants fleeing the Great Famine who arrived in New York City were primarily destitute and forced to live in Five Points tenements, a horror show on many levels. Most of the Irish Catholic immigrants were monolingual, speaking only the Irish language. Five-eighths of the residents in Five Points in the late 1840s spoke Irish.

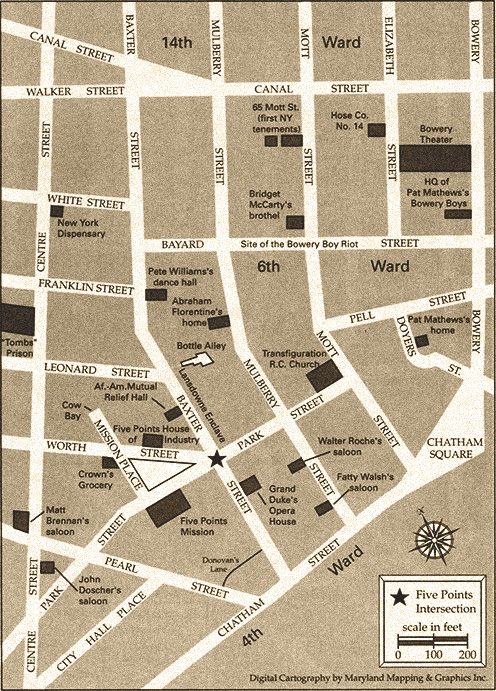

Facts about Henry McCarty’s early life have been extremely elusive, which has frustrated historians for decades. Certainly, immediately after the Kid’s death, articles claimed that he was born in New York City, and none of Billy’s amigos stepped forward to contradict that assertion. In addition, Ash Upson claims Billy was born in New York in The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, the biography he had written for Pat Garrett. An immigrant from Tipperary, Ireland, Bridget McCarty had a brothel on Mott Street, just a block from the Church of the Transfiguration, also on Mott Street, the heart of the Irish ghetto.

Unknown artist, circa 1827, Bequest of Mrs. Screven Lorillard (Alice Whitney), from the collection of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 2016, Courtesy Metropolitan Museum Art, DP265419

In Five Points, prostitution offered young destitute women far better pay and working hours than any other job available to them. For the clientele who frequented brothels, very young girls from 10 on brought a premium and an even bigger premium if still a virgin. From a police report, Bridget’s young niece, 14 years old, came from Tipperary, headed to her aunt’s establishment and was immediately put in the family business. Another young girl at the same time hated that business and made out a report for the police, which, of course, brought an investigation. Bridget’s niece was interviewed as well but did not give a deposition too harmful to her aunt. The other girl was let go, and Bridget resumed business as usual.

Could it be that Bridget brought another niece from Tipperary, perhaps named Catherine?

There were many other bordellos in Five Points. It is known that Italian, German and Irish immigrant girls who were Catholic kept their children and did not abort—as Protestant prostitutes usually did—fearing that their souls would be damned to hell, considered by the Catholic Church as a sin so monstrous, it could never be forgiven.

Catholic prostitutes had their babies in the brothel and never registered the birth since their child would be listed as illegitimate with no known father. In addition, these girls and women avoided the census-taker if they could, as they did not want to be officially listed in known brothels.

When these ladies were approaching 30, they knew they had to make a choice since clients preferred younger females. The women usually kept half of their fees, which they saved up in order to take their children far away from New York City to begin a new life as a widowed woman, instantly “legitimizing” their children.

True West Archives

Remember that Catherine McCarty was married to William Antrim in a Presbyterian church in Santa Fe. If she indeed had been brought up as a Catholic, she would have been married in a Catholic church. She would had to have done a confession to the priest, and she could never admit these sins. To avoid this unpleasantness, a Protestant church wedding did very well indeed. If the reader feels this could be plausible, then Billy and his brother being half brothers makes perfect sense. Some who knew them both in Silver City seemed to express that opinion.

Courtesy Chuck Usmar III Collection

Finally, if Billy did indeed spend his early years in Five Points, he would certainly have absorbed the Irish language, the same as he did later with Spanish. He certainly had a gift for rapidly absorbing other languages. In tapes that were done with Louis Blatchly, recorded in the early 1950s, one of those interviewed was an old cowboy named Clark Hust. As a kid, his parents let him work for Pat Coghlan, an amigo to the Kid and sometime-supplier to the government of stolen beef. Clark says that Coghlan had brought over his niece Mary from Ireland and hoped she would stay since the Coghlans were childless. Mary, however, could only speak Irish, not a word of English. Pat was an Irish immigrant and did speak the language,

so he was the only one who could communicate with her, that is until Billy showed up. According to Hust, Billy translated for her with the cowboys. That was the only time he saw Billy, and that’s basically all he remembered about the Kid. In the present time, most Americans don’t even know there is an Irish language.

Courtesy Chuck Usmar III Collection

Presumably, the Coghlans, like other Irish-Americans who knew Irish, only spoke that language when the other spoke only Irish, and that would have been rare in the New Mexico Territory. His story seems credible to me, but judge for yourselves!

Author’s Note: Perforce, anything about Henry McCarty’s earliest years must be conjecture since no unimpeachable documentation has survived. The most plausible explanation may be as I have given. From the many conjectures seen over the years, each Kid enthusiast must judge for himself or herself.

In his blog, Bob Boze Bell called Chuck Usmar III a “crackerjack researcher” and he has assiduously done research in Ireland, making two trips of nine days each, as well as in the archives of New Mexico, Utah, Texas, Arizona and New York City.

Edward Bonney: Could He be Billy’s Father?

By Susan Stevenson, Gary Jones and Donald Bonney

–

It has been established that in 1860 a 30-year-old domestic servant named Catherine McCarty was working in the home of the wealthy John Munn family in Utica, New York. A couple of years earlier, brothers John J. And Edward Finch Bonney lived on the same block of Munn’s Castle.

While it is not established when Catherine arrived in Utica, it is highly probable she and the Bonney brothers were living there at the same time. We hypothesized that Catherine may have had a relationship with Edward Finch, as John J. had taken a wife. The Bonney family lived in Hamilton, New York, and appeared to be in the upper class. They possibly would not allow a servant to join their family and left Catherine with an illegitimate boy named William Henry McCarty.

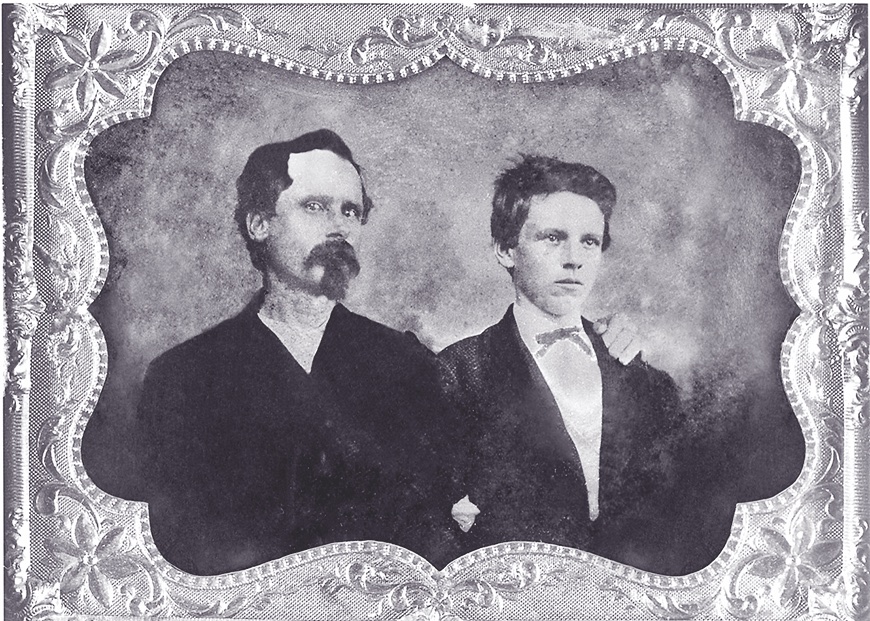

Courtesy Ruth Almira Bonney Hatch Family Collection

The Bonney family believes the photo is Edward and Almira Bonney and children Villa and Homer, from Donald Bonney’s Aunt Ruth Almira Bonney Hatch’s collection (note that Ruth’s middle name is the same as her grandmother’s).

So could this be Billy the Kid’s father and half-siblings?

Donald Bonney thinks so.

“I still feel intuition (not worth anything research-wise) that Billy the Kid was Homer’s known (or maybe unknown since scandals in those days were kept hidden) half brother,” says Bonney, “which would certainly account for my being told at one time that he was a relative.”

Edward Finch Bonney

b 12 Apr 1834

d 19 Apr 1910

Almira C Davenport

b 1835

d 2 Jul 1896

Villa J Bonney (spinster)

b 1 Jan 1860

d 1943

Homer Levi Bonney

b 3 Dec 1870

d 21 Dec 1943

Gary Jones is a retired nuclear reactor operator. His daughter Susan Stevenson is a professional tax accountant. They have specialized in the Lincoln County War and Billy the Kid research for over 27 years, working closely with Kid biographer Fred Nolan. Donald Bonney is a descendent of Edward Finch Bonney.

More than a Coincidence

By Gary Jones and Susan Stevenson

–

Did Catherine McCarty live in Indianapolis in 1867-1868?

Illustration by Bob Boze Bell, True West Archives

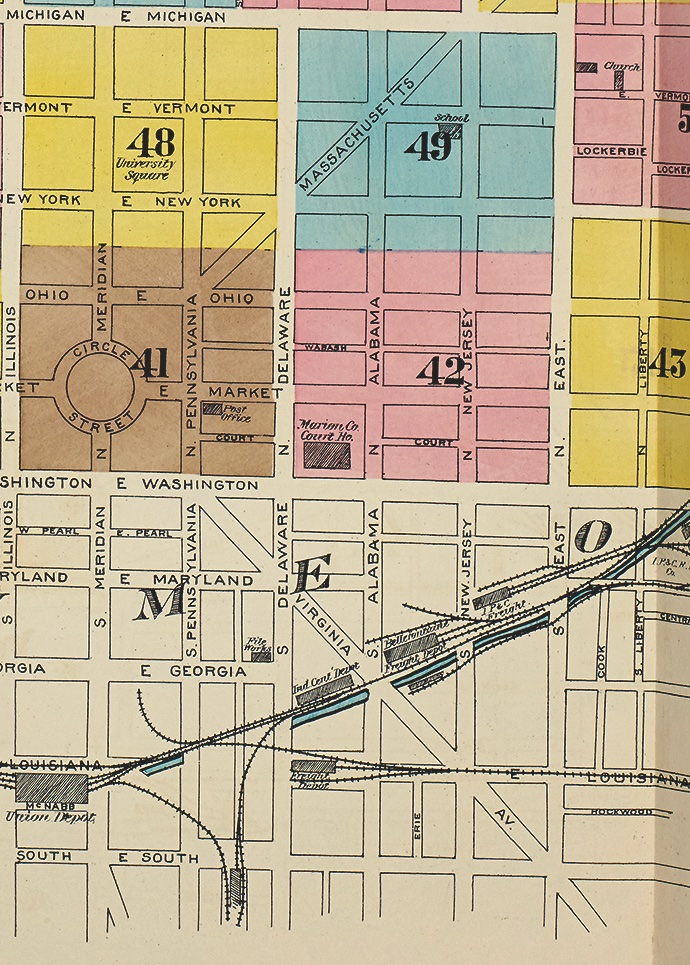

Historians have discussed and assumed the Catherine McCarty living in Indianapolis in the 1867 Edward’s City Directory, was in fact Billy the Kid’s mother. The City Directory lists a Catherine McCarty residing at 385 N. New Jersey Street as the widow of Michael McCarty. No ages or children were listed in the directory, so it was an unconfirmed assumption.

Billy’s mother, Catherine, in later years, married William Antrim, who also lived in the Indianapolis area. William and Catherine ended up in Wichita, Kansas, by the summer of 1870. In Wichita, William Antrim gave a supporting statement as the law required for ownership of Federal land to be purchased, “I have known Catherine McCarty for six years past; that she is a single woman over the age of 21 years and the head of a family consisting of two children and a citizen of the United States.” This would indicate that they met in the year 1864.

Courtesy Library of Congress

In the 1868 Logan’s City Directory, Mrs. Catherine McCarty, widow of Michael, had moved to 199 N. East Street. At that time William Antrim and Frederick Hoffmeyer were driving for the Merchant’s Union Express Company. The previous year, Frederick Hoffmeyer’s brother William, lived at the 199 N. East Street residence. It is clear that there are connections between Catherine, Antrim and the Hoffmeyers.

We conclude that Catherine McCarty, mother of Billy the Kid, was indeed the widow of Michael McCarty. The connection between William Antrim and Catherine McCarty in Indianapolis has been firmly established.

The Disputed Pictures of Billy the Kid’s Mother

By Roy B. Young and Kurt House

–

True West Archives

On March 16, 1978, Robert N. Mullin wrote James D. Horan the second of two letters in which they discussed the commonly proffered picture of Catherine McCarty Antrim. The first letter was somewhat brief; below is the more detailed information from the second one:

[Noah] Rose [collector of photographs of frontier characters] was sometimes the victim of misrepresentation. Eugene Cunningham, with whom I became acquainted when he went to El Paso to live after his discharge from the Navy at the close of World War I, gave me an example of this doubtful labeling in later years when I visited his home in San Francisco. [When Gene’s] Triggernometry appeared in 1934, it contained a picture bought from Rose, identified as “Mrs. Catherine Antrim, mother of Billy the Kid.” The book had not been on sale long before Gene received a letter from a man in Kansas or Nebraska…. The letter enclosed a photograph of the lady Gene had introduced as Billy the Kid’s mother. The name of the photographer appeared on the card with the date “1889.” The letter to Cunningham identified the lady as the writer’s mother, whose name was nothing like Antrim or Bonney. The picture had been identified by other members of the family and, after her death, had been properly identified by surviving friends.

Gene did not want to publicize his mistake in print but planned a revised edition of Triggernometry, correcting a few minor slip-ups and showing the authentic photograph of the Kid’s mother, one taken by a photographer at Silver City in 1873. This picture was identified as Mrs. Catherine Antrim by Sheriff Harvey Whitehill, and Chauncy Truesdell and others who had lived in Silver City during the early 1870s.

This photograph and one of the very youthful Henry Antrim were used in my [book] The Boyhood of Billy the Kid, having been obtained by me from Lawrence E. Gay, of Lordsburg, New Mexico, who had secured them from the effects of John B. Morrill, who had been proprietor of Silver City’s first theatre, modestly named Morrill’s Opera House. It was on that stage that, according to young Antrim’s school teacher, Miss Mary Richards, Henry had played the role of a little girl in a play staged by local talent. I never recovered these photographs which were supposedly mailed back to me but lost in the mail.

Roy Young Collection

The authors contend that the usually published picture of Catherine McCarty Antrim is the misidentified photo obtained by Eugene Cunningham from Noah Rose. Nib Jones, son of Barbara “Ma’am” Jones, told historian Eve Ball, “Billy…gave us his mother’s tintype.” Likely lost to time, if this picture could be located, it would clear up the question of authenticity of the image of Catherine McCarty Antrim.

As to the veracity of the Gay/Morrill/Mullin photograph of Billy the Kid’s mother, the reader will have to decide their own acceptance or rejection.

Roy B. Young is the Publications Editor for the Wild West History Association. He has authored 12 books on Wild West characters. Kurt House is a historian, Western collector, director of the WWHA and author of several books on Western Americana. Their next book focuses on the chase and capture of Billy the Kid in 1880.

Mile-High Hideout: Was the Kid in Prescott, Arizona Territory in 1876?

By Susan Stevenson and Gary Jones

–

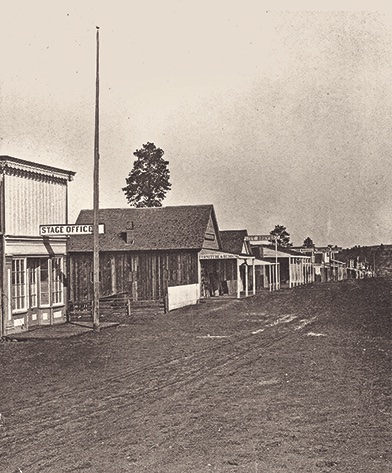

Courtesy Sharlot Hall Museum Library Archives

In September 1875, William H. McCarty fled Silver City, New Mexico Territory, heading toward Globe, Arizona Territory. According to Frederick Nolan, his first stop was near Clifton while working in the Gila River Valley. Other historians believed that McCarty went to Globe, where he reportedly killed a Chinese man. No proof has ever been furnished to verify this story. Reportedly, he was at Camp Goodwin on March 19, 1876, heading to Fort Grant after stealing a horse. His reputation as a thief was already spreading in the Southwest.

Various historians have tried unsuccessfully to make a stab at determining his whereabouts between March and August 1876. One historian has him possibly in Wichita, Kansas, another in New York and yet another in Mexico.

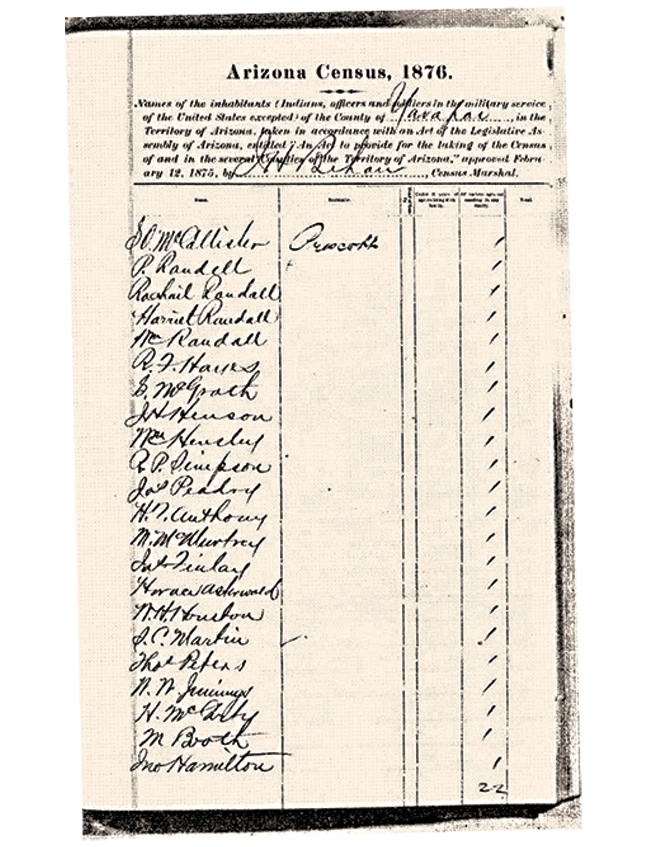

We believe none of the above, as new information has come to light. We have located an Arizona State Census which lists H. McCarty on the roll in Prescott. It’s no wonder he was historically absent the summer of 1876, since Prescott is located a couple of hundred miles northwest of the Gila Valley. Prescott was the original Territorial capital of Arizona, established a dozen years prior due to the booming mining districts. The usual bars and houses of ill repute were prevalent so young Billy could have found some sort of employment.

This was also the home of the now infamous John Harris Behan. He was the county clerk in the summer of 1876 and was the actual census-taker for the town of Prescott. The census was filed in Yavapai County on July 3, 1876. He moved on and was the sheriff of Tombstone during the famous gunfight behind the O.K. Corral.

Also noted on the 1876 State Census were future Billy the Kid compatriots Jesse Evans and John Mackay and adversary W. Cahill in the Globe district. Windy Cahill tangled with McCarty on August 17, 1877, at Camp Grant. Cahill lost, and on that date, Billy graduated from being a horse thief to a full-blown outlaw.

Justified Homicide

By James Townsend

–

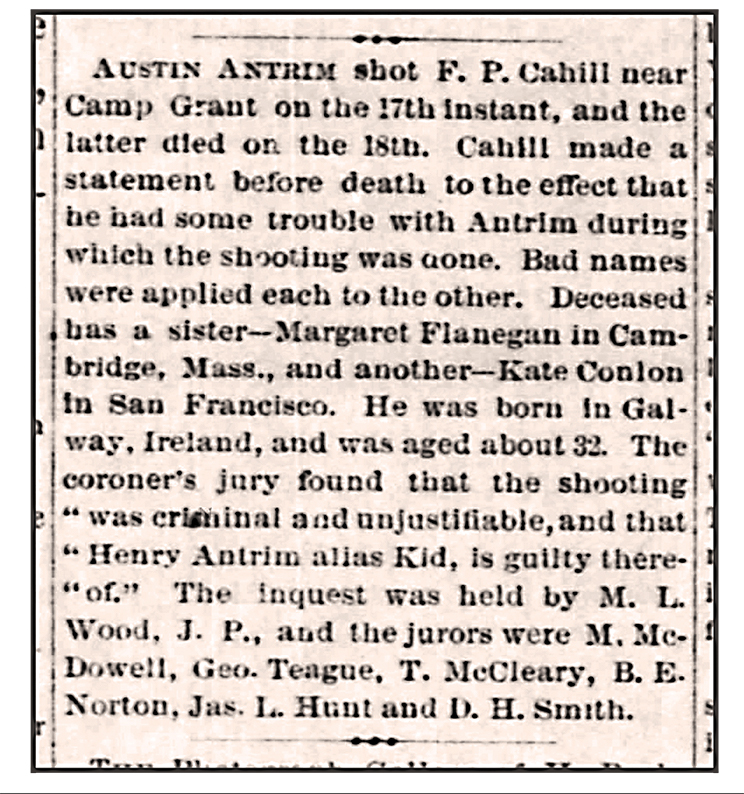

If Billy hadn’t fled his killing of F.P. Cahill, would he have been acquitted?

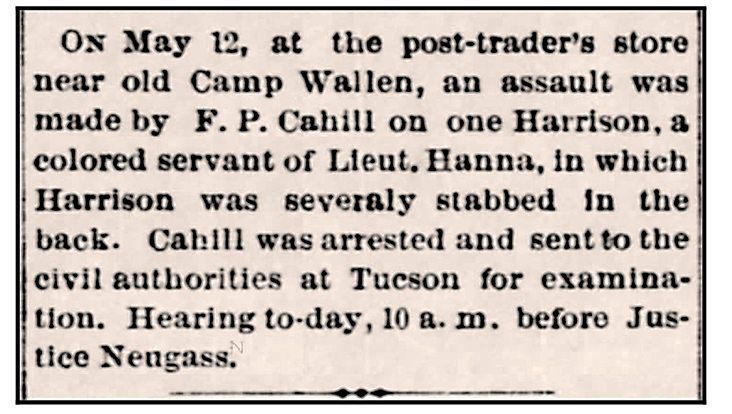

Recently, I uncovered evidence about F.P. “Windy” Cahill that sheds light on his true character. From Tucson’s Arizona Weekly Citizen on May 19, 1877, just a couple months before he was shot by Billy:

“On May 12, at the post-trader’s store near old Camp Wallen, an assault was made by FP Cahill on one Harrison, a colored servant of Lieut. Hanna, in which Harrison was severely stabbed in the back. Cahill was arrested and sent to the civil authorities at Tucson for examination. Hearing today, at 10 am, before Justice Neugass (Nengass?)”

In the J.R. Mackey vs Knox incident in 1875, Mackey was let off the hook for shooting Knox in the throat. The reasoning of the court:

“The defendant acted in the necessary defense of his person; that TR Knox, the wounded party, acted in a riotous and violent manner and was the assailant on several occasions as is stated in the evidence; that although it is shown that Knox was not armed, but his action and assault on the assault made upon defendant were of such a character as to excite the fears of a the defendant as a reasonable man: that the right to defend one’s person is founded in necessity, and the evidence in this case does clearly show that Knox being a muscular man and defendant no match for him… .”

If you replace “Knox” with Cahill and “Mackie” with Antrim, it’s not hard to see the same reasoning could have applied to Billy. Hard to say how history would’ve turned out if the Kid had stuck around to plead his case.

The coroner’s jury for Cahill, however, seemed oddly in favor of the victim.

James Townsend is an independent historian from Charleston, West Virginia.

By Susan Stevenson and Gary Jones

The Kid and His Blooded Horse

By Susan Stevenson and Gary Jones

–

Was Billy’s “Dandy Dick” favorite mount one of Col. Emile Fritz’s racing stallions?

On September 6, 1878, Billy the Kid and a few of the Regulators stole horses and cattle from the Fritz Spring Ranch and headed toward Fort Sumner and the Texas Panhandle. Were these Lt. Col. Emil Fritz’s racehorses he brought from California or possibly their offspring?

Hilario Gallego quoted in his manuscript located in the Tucson Museum: “In 1862 the California Column of the Union soldiers came to Tucson. They were under the leadership of Col. Fritz, a German. The Colonel had some fine racehorses. I remember one was named ‘Dandy’ and he made me his jockey. After the war he took me East with him. I traveled with the horses for five years and went as far east as St. Louis. Then I came back to Santa Fe and later to Tucson.”

Brigadier General James Henry Carleton (commander of the California Column and Department of New Mexico) showed a strong interest in the racehorses. During the war Carleton sent communications to Capt. William McCleave and Capt. Fritz asking for reports on the condition of the grazing camps near posts where they were stationed. Fritz was ordered to inspect and report upon the condition of “certain horses” in his charge throughout the war.

The military records indicate the horses never got far from Fritz’s command. On one occasion during New Year’s Eve 1863, Fritz had two horses stolen outside the door of his quarters in Tucson. He pursued the thieves 300 miles into Mexico before recovering them. Another time in the spring of 1863, McCleave chased a group of Indian horse thieves 30 miles out of Fort West to recover a group of stolen horses. The Indians paid dearly with a reported loss of 25 lives for their escapade.

Sheriff William Brady and Emil Fritz were friends and neighbors, so just maybe Billy’s horse, Dandy Dick, which he sold to Dr. Henry Hoyt in Tascosa, Texas, had some Fritz racing horse blood in him.