The highly respected Texas actor and director reflects on a 50-year career in Hollywood.

Courtesy Warner Bros./Seven Arts

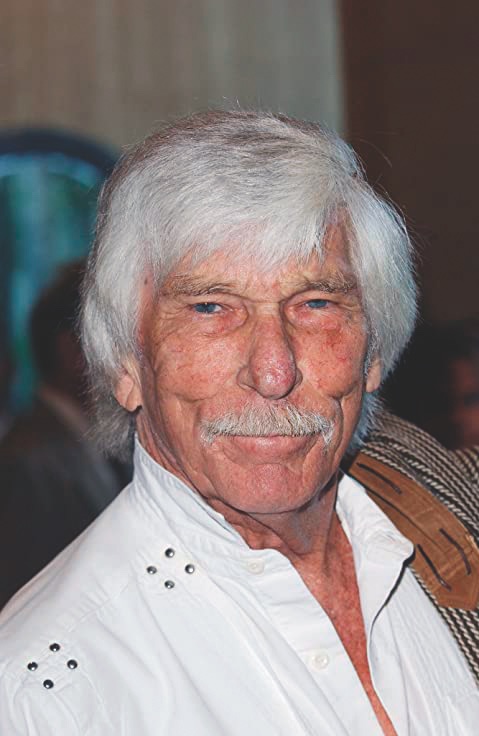

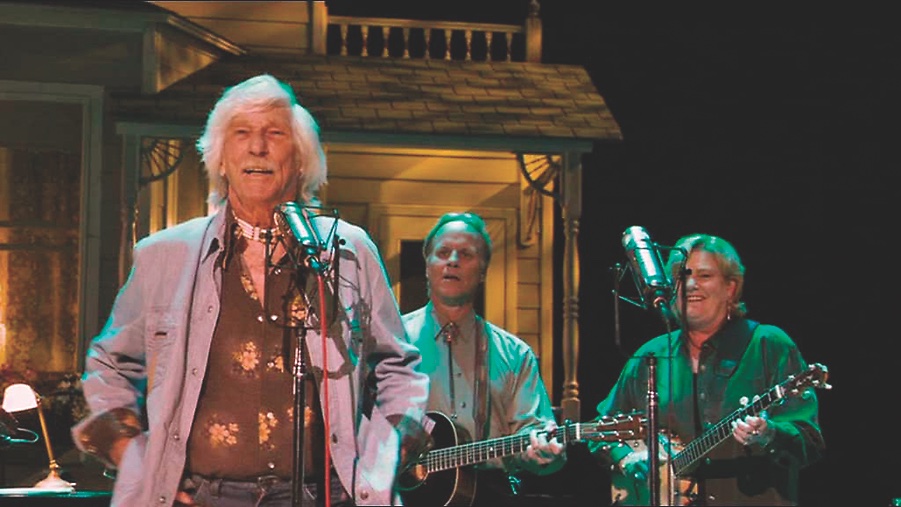

L.Q. Jones, the sandy-haired giant with the high cheekbones, warm smile and ice-cold blue eyes, is set to celebrate his 94th birthday this August. He’s been a constant, mostly menacing, screen presence for five decades. His last film was 2006’s Prairie Home Companion. The veteran of hundreds of big and small-screen performances recently told True West, “We didn’t know it while it was taking place, but when we did The Wild Bunch, it changed the way the pictures were accepted, changed them 180 degrees. And, oddly enough, I happened to be in another picture, The Mask of Zorro, that changed it back.” He explained that the former brought an unflinching look at brutal violence, and the latter marked a return to thrills with less realistic blood-letting. It’s no surprise that his lengthy career has bridged many cinematic trends.

He got his boot in the door thanks to his former University of Texas in Austin roommate, Fess Parker, who also got fraternity brother the late Morgan Woodward his first role. Woodward recalled, “Fess sneaked him in to see director Raoul Walsh, and L.Q. is so crazy, he convinced him that he ought to be in the picture.” It didn’t hurt that Fess, by then TV’s Davy Crockett, also got writer and future director Burt Kennedy to rewrite L.Q.’s dull audition scene. L.Q. was so pleased with the role that he took his character’s name for his own; until then he’d been Justus McQueen.

From 1955 on, he recalls, “Between war movies and Westerns, work was constant.” He was sidekick to Clint Walker on Cheyenne, did three movies with Elvis Presley, including the excellent Flaming Star, and guest-villained on series like Annie Oakley, Rin Tin Tin, The Rebel, The Rifleman, Have Gun Will Travel and Laramie.

“I was regular on about seven Westerns.” About The Virginian, on which he played ranch hand Beldon, he says, “We became a family. We were putting on a new Virginian every other week. You had two weeks to make an hour-and-a-half show, which is a full motion picture.”

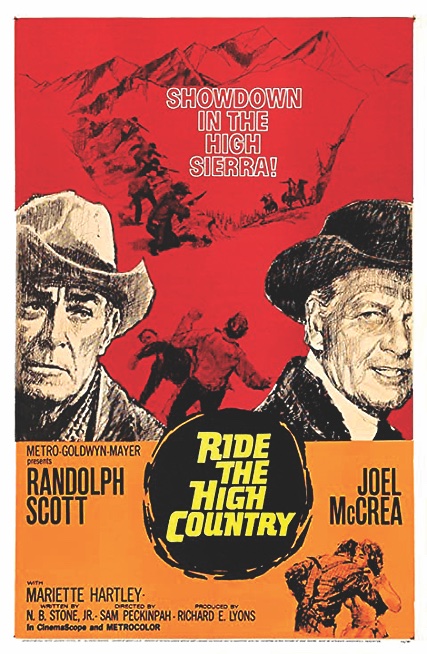

Courtesy MGM

The seed of one of his biggest breaks was planted in 1955, but took a few years to flower. Annapolis Story director Don Siegel’s dialogue coach, Sam, took a liking to L.Q. “At the end of it, he said, ‘Listen, kid, I guarantee you we’re going to be working together, because I’m going to be a director, and I will remember you.’ And I said, ’Yeah, thanks a lot. Heard that before.’ Later I was in my agent’s office and they called and wanted me for Ride the High Country, and I realized it was Sam Peckinpah.” Counting shows that didn’t work out, “We ended up doing, I think, 17 projects together.”

Courtesy CBS Television

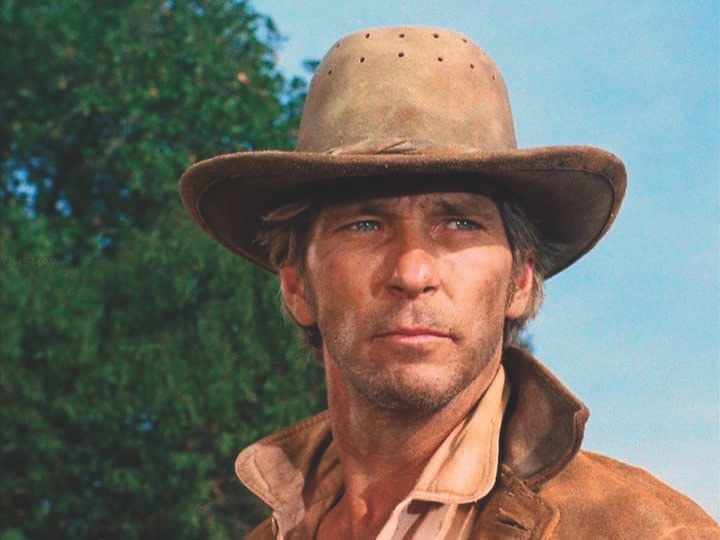

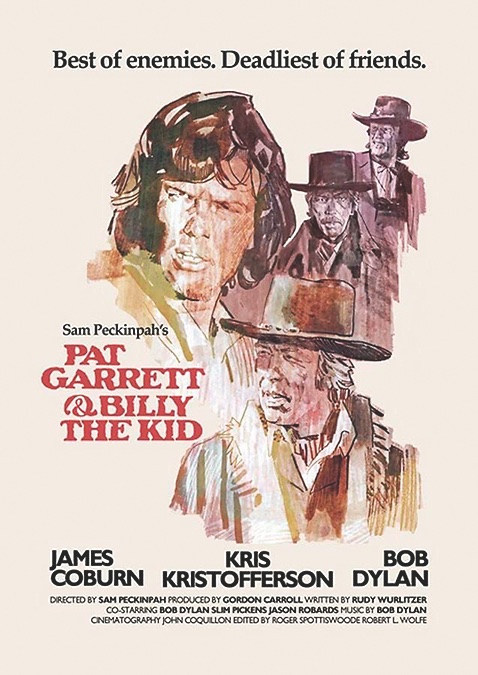

“Sam, if he was good at two things, it was attention to detail and casting the right people. The man was a genius, but Sam had a strange way of operating, sort of like John Ford’s.” He purposely created hostility between members of the cast and crew. “He has you so overwrought that everybody detests everybody else. And then he starts to put you back together. And within a week, there’s only one human being in our universe, and that’s Sam Peckinpah. It worked for him until we got into Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. He tore us down, and then Sam was so sick that he couldn’t put us back together.”

Courtesy TriStar Pictures

A man of many talents, Jones adapted and directed Harlan Ellison’s sci-fi novel, A Boy and His Dog, which starred Jason Robards and helped make a star of Don Johnson. He produced The Brotherhood of Satan, giving his frequent co-star, Strother Martin, one of his best non-Western roles, “And in one scene, he’s completely nude. Just for a few frames.”

Courtesy MGM

But above all, L.Q. Jones is an actor. “I know this sounds Pollyannish, but any show I do is my favorite for the moment.” But for TV Westerns? “I did seven Gunsmokes. Over the years, almost everything I’m in, they ask me to change it, to fit me. Not on Gunsmoke. You take what they give you, hit your mark, say your words and pick up your check. Because they’ve done a hell of a job, the writers, the producers, the crew. They were so professional in what they did.

Courtesy Picturehouse

“I did the Gunsmoke where the entire cast, with the exception of the regulars, was black. And I played a terrible person. A racist, I kicked dogs, beat kids, chased women. The Monday after they showed it, I had about a 45-minute trip to the studio. I was driving my MG, top down, and I was booed and hissed for the entire 30 miles. They had all seen the show, and they were throwing things. You know you made an impression. The other shows I enjoyed as much, but that is my favorite because of what happened after the fact.”

Henry C. Parke, Western Films Editor for True West, is a screenwriter, and blogs at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com. His book of interviews, Indians and Cowboys, will be published later this year.

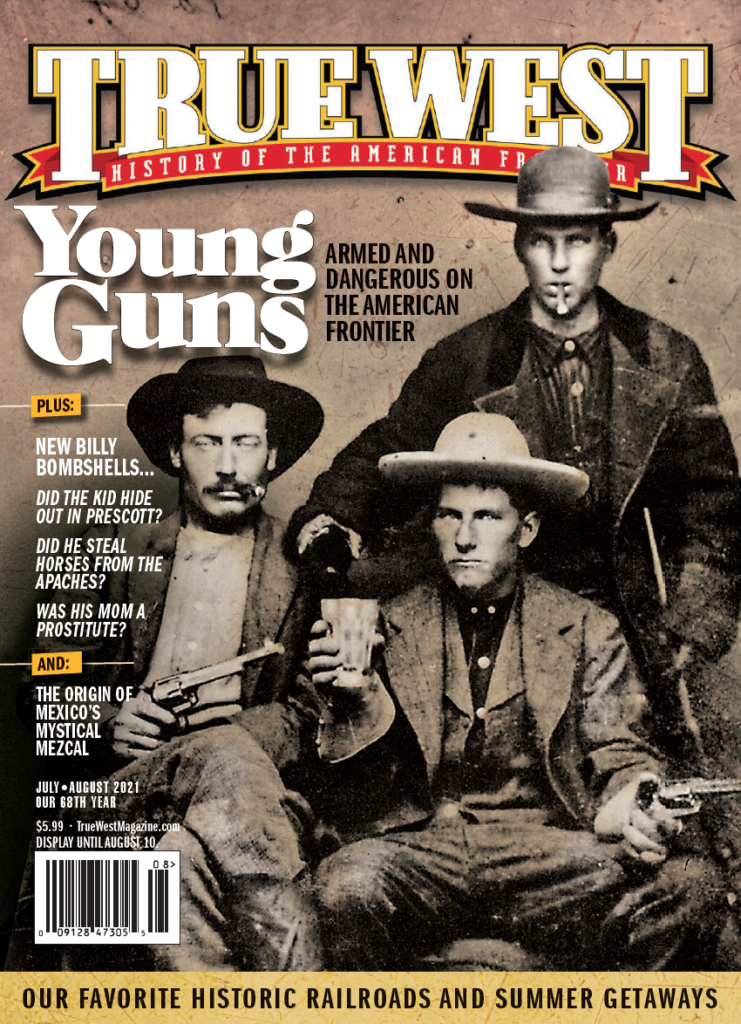

Battle of the Billys

The legendary Western outlaw is saddling up to return to film and television as early as 2022.

Two high-profile Billy the Kid projects have appeared on the none-too-distant horizon: one a movie sequel, the other a miniseries.

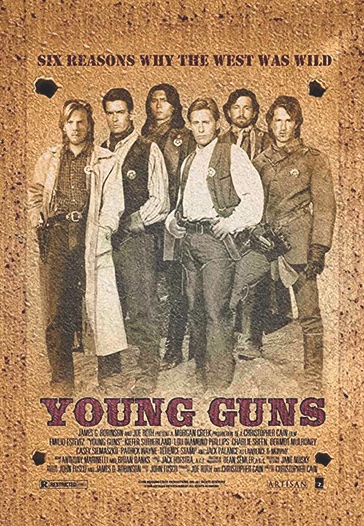

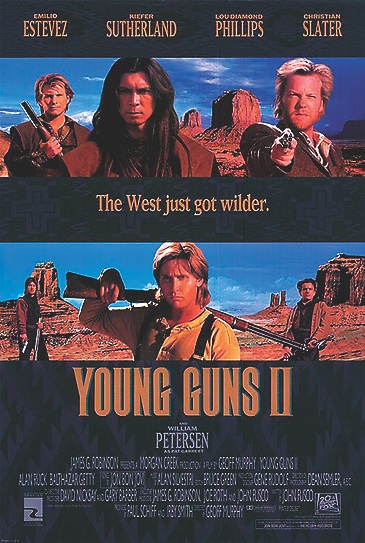

Back in 1988, Emilio Estevez made an indelible impression with his maniacal Billy in the surprise hit Young Guns and the sequel, Young Guns II. Now Estevez says a follow-up “is definitely in the works.” He’ll star and direct, and is collaborating with the author of both earlier films, John Fusco, on Guns III: Alias Billy the Kid—the artwork playfully has the word “Young” obliterated with bullet holes.

Epix and MGM have announced an eight-part Billy the Kid series, a romantic adventure written and produced by Englishman Michael Hirst, who wrote Elizabeth and The Tudors and Vikings. Photography will commence in Calgary in June, with English actor Tom Blyth in the title role.

While some dismissed Young Guns for having so many handsome actors—Kiefer Sutherland, Charlie Sheen, Lou Diamond Phillips, et al—Western historian Paul Hutton calls it the “first film to do full justice to the Regulators, and to play most events of the Lincoln County War accurately.” To make the first sequel after killing off the lead character, Guns II was told in wraparound segments by Brushy Bill Roberts, who in 1950 claimed that he was the real Billy, and that Pat Garrett had killed someone else. While calling Brushy’s story “unproven” is generous, letting Billy live until 1950 opens up all kinds of plot possibilities for Guns III. Are the original stars interested in returning? Phillips speaks for most or all: “I’d show up in a heartbeat.”

“Michael Hirst is one of the most gifted and prolific storytellers in this exciting new TV landscape,” notes Fusco. “He also has a palpable love for complex historical epics and knows how to slow-burn a saga. Personally, I am looking forward to his vision of the Lincoln County War and his take on William Bonney.”

“Billy the Kid has always been a hero of mine since I was—well, a kid!” Hirst told The Hollywood Reporter about his limited series for Epix Studios and MGM International Television Productions. “He was an outlaw…but he never wanted to be. Born into a poor Irish family of immigrants, he always wanted to go straight, to be a ‘new American.’ But he was never allowed to… In the end it’s not just a story at all—it’s an American myth!”

—Henry C. Parke

Ent./20th Century Fox