– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Shortly after Jesse James’s death, journalist John Newman Edwards, longtime supporter of the James and Younger brothers, negotiated with Governor Crittenden for Frank James’s surrender. On October 5, Edwards introduced Frank to the governor, and the outlaw handed him his gunbelt, saying, “Governor Crittenden, I want to hand over to you that which no living man except myself has been permitted to touch since 1861, and to say that I am your prisoner.” That was impossible, however, since the revolver was a model 1875 Remington.

Frank was brought to trial in Gallatin, Missouri, in 1883 for the Winston train robbery. The trial of the century was a media sensation, with six attorneys heading the state’s prosecution, and eight defending Frank James. Perhaps fittingly, the trial was held in an opera house. On September 6, after less than four hours of deliberation, the jury brought in a verdict of not guilty. The following year, Frank was tried in Huntsville, Alabama, for the Muscle Shoals robbery, and again acquitted. In 1885, the state of Missouri dropped its last case against Frank, who became a free man. He was never tried for the Northfield robbery.

– Jesse James Farm Tourist Brochure Courtesy Library of Congress/Photo of Zerelda James Samuel Courtesy True West Archives –

By then, the James brothers were big news.

Shortly after Jesse’s death, a song, perhaps written by a minstrel named Billy Gashade, became popular. Its chorus went:

Jesse had a wife to mourn for his life, Three children, they were brave,

But that dirty little coward that shot Mr. Howard Has laid Jesse James in his grave.

– Photos Courtesy True West Archives –

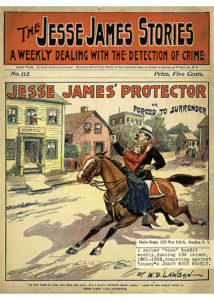

Even before Jesse’s death, books had been published about him. Edwards’s Noted Guerrillas, Or, The Warfare of the Border came out in 1877, two years after Augustus C. Appler’s The Guerrillas of the West; or the Life, Character, and Daring Exploits of the Younger Brothers. In 1881, the Five Cent Wide Awake Library began publishing stories about the James gang. After Jesse’s death, books—often sporting titles like Jesse James, the Midnight Horseman; or, The Silent Rider of the Ozarks; and The James Boys and The Mad Sheriff; or The Midnight Run of ’99—became popular; William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was most likely the only actual person who appeared as a hero in more dime novels than Jesse James.

Bob and Charlie Ford appeared in a traveling play, How I Killed Jesse James. Zee James and Zerelda Samuel were alleged to have countered by contracting with Frank Triplett for his book The Life, Times and Treacherous Death of Jesse James.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

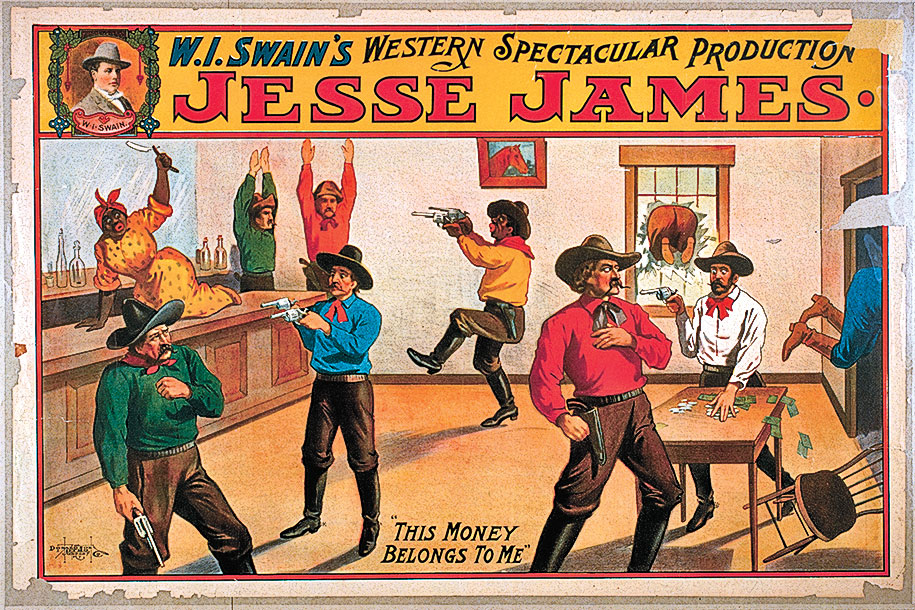

By the 1890s, plays about Jesse James, including W.I. Swain’s Western Spectacular’s Jesse James, were commonplace, and highly fictitious. Even Cole Younger, paroled in 1901, and Frank James got in on the act. In 1903, they toured the country in The Great Cole Younger & Frank James Historical Wild West show.

Few books and plays had any semblance to history. As Frank said: “If I admitted that these stories were true, people would say: ‘There is the greatest scoundrel unhung!’ And if I denied ’em, they’d say: ‘There’s the greatest liar on earth!’ So I just say nothing.”

The same year that Frank and Cole Younger launched their Wild West exhibition, Pennsylvania-born Edwin Stanton Porter, fledgling filmmaker in the fledgling film industry, shot a Western-set motion picture, The Great Train Robbery, in New Jersey. Response to the movie was so tremendous that nickelodeons began springing up across the nation. “From then on,” film historians George N. Fenin and William K. Everson wrote, “the Western was a genre of the American cinema.”

– Courtesy True West Archives –

It wouldn’t take long before filmmakers decided to spotlight Jesse James.

“Birth of an Outlaw Hero: Jesse James in Pop Culture 1875-1903,” is excerpted from Jesse James and the Movies © 2011 Johnny D. Boggs by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640; McFarlandBooks.com