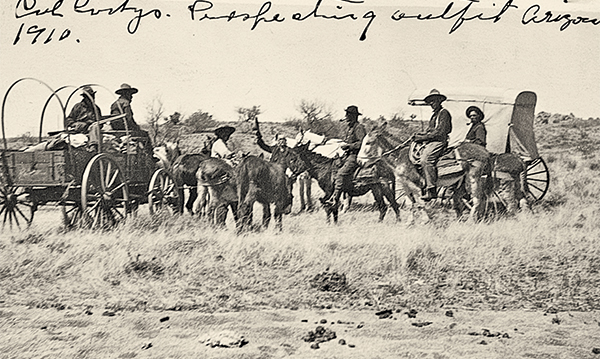

– All images Courtesy Patsy Garlow Collection of William F. Cody Family Photographs, Cowan’s Auctions, January 31, 2014 –

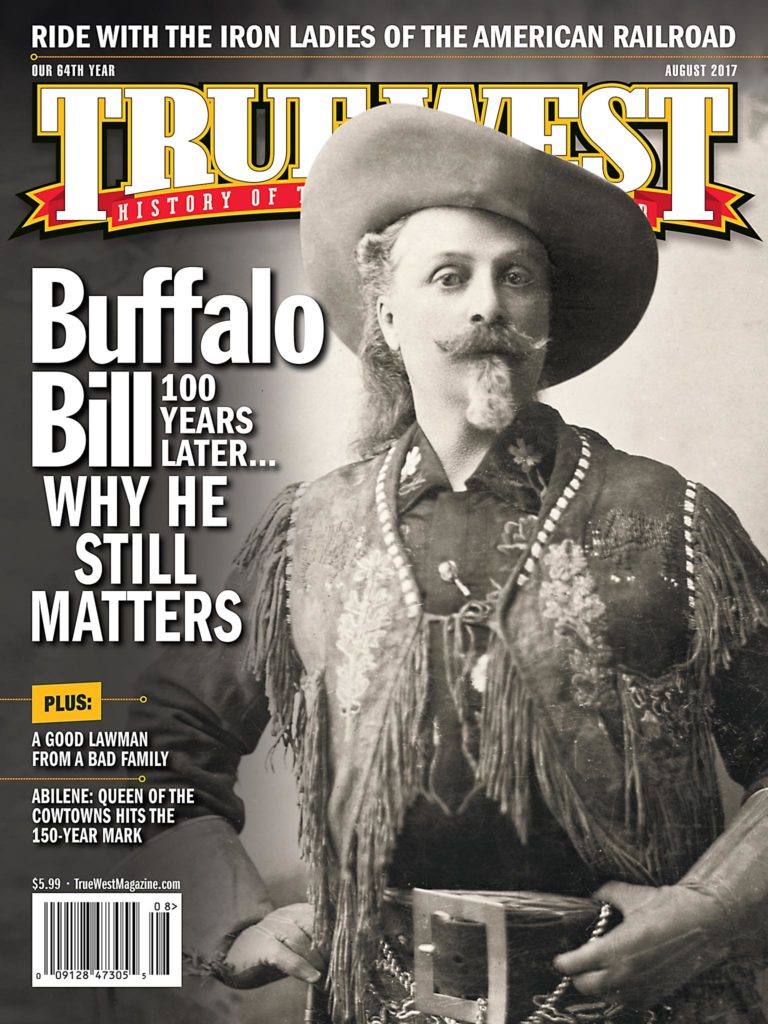

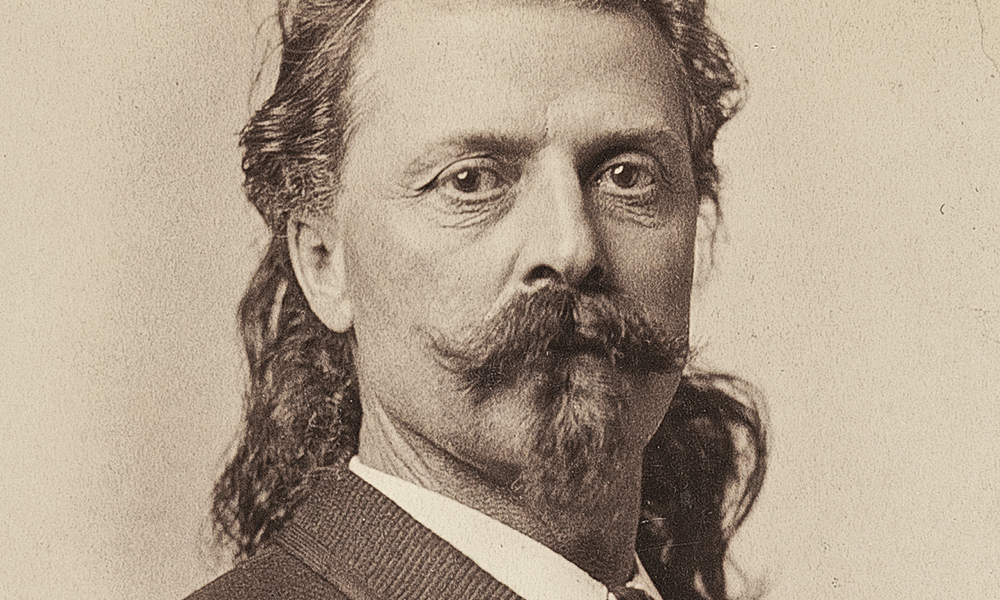

William “Buffalo Bill” Cody was a lucky man.

From a hardscrabble youth that began in a log cabin in Iowa Territory, he grew up to survive the Civil War, the Indian Wars, and buffalo hunts to create a Wild West show that traveled the globe and made him the most famous man on earth.

But his luck ran out in Arizona Territory in the last decade of his life.

Arizona wouldn’t give him the pot of gold he sought in one mining claim after another. Nor silver or copper. All his claims turned up wanting, costing him as much as a half million dollars—almost $12.5 million in today’s money. That shattered his dream of a comfortable retirement and gave him financial heartbreak instead.

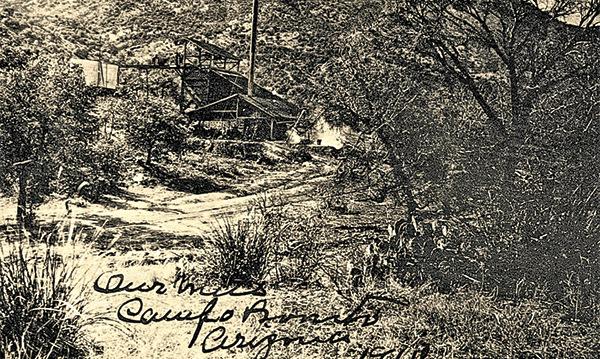

Blame it all on a little piece of scenic heaven known as Oracle, just north of Tucson, where, in 1910, Buffalo Bill started pumping money into mines sold to him as “sure things.”

“He got salted,” says Chuck Sternberg, curator of the Oracle Historical Museum, which displays several pictures of Buffalo Bill in the days when he was a town fixture.

The dry holes would force Buffalo Bill to abandon his hope of retirement in his mid-60s, sending him back on the road for yet more seasons of Wild West shows—but smaller now, sometimes in collaboration with Gordon “Pawnee Bill” Lillie, as he could no longer afford the extravaganzas that had made him so famous.

But his mining failure didn’t seem to dampen his good name in Arizona Territory, where folks talked of running him for the U.S. Senate when statehood finally came on February 14, 1912. And the children of Oracle certainly didn’t mind that his mines were worthless, not when he showed up dressed as Santa Claus and delivered presents to all—a bit of showmanship that never failed to draw a smile.

No, Arizona Territory wasn’t lucky for Buffalo Bill—either his pocketbook or his health—and that was downright rude.

A Millionaire Without Millions

At the turn of the 20th century, Buffalo Bill was a millionaire without millions. He was a generous soul who gave freely, once saying, “…when I die, people will say, ‘Here lies Bill Cody, who made a million dollars in the show business and distributed it among his friends.’”

He was proud that many considered him the ultimate self-made man, a boy who lost his father at 11 and went on to become a household name around the world. If he had a hankering, it was for a gold mine.

“Wouldn’t it be great if a fellow had a good gold mine,” he once told Pawnee Bill, “so that when he needed some more money all he would have to do would be to send some miners down the mines and bring it up. And that way you would not be taking a thing away from anyone else.”

But he didn’t grab for his hankering until after his Wild West show suffered its most devastating loss.

On October 29, 1901, outside Lexington, North Carolina, a freight train crashed into the second train of Buffalo Bill’s caravan. More than 100 horses died, including his personal mounts, Old Pap and Old Eagle. All the people escaped, but sharpshooter Annie Oakley suffered severe injuries and said the trauma caused her hair to go white overnight. She never performed for Buffalo Bill’s show again.

The loss put the show out of business for a time, and Buffalo Bill himself saw it as the start of his final financial struggles, saying this was the calamity that changed his life.

In 1908, he would meet its twin.

A Fortune Down There

In 1892, Buffalo Bill was asked to mine a different kind of gold in Arizona Territory—tourism gold. Franklin Woolley and Brigham Young’s son John hired the showman to escort a group of English nobility to places that included the majestic Grand Canyon, in order to encourage the men to game hunt and ranch in the Arizona wilderness.

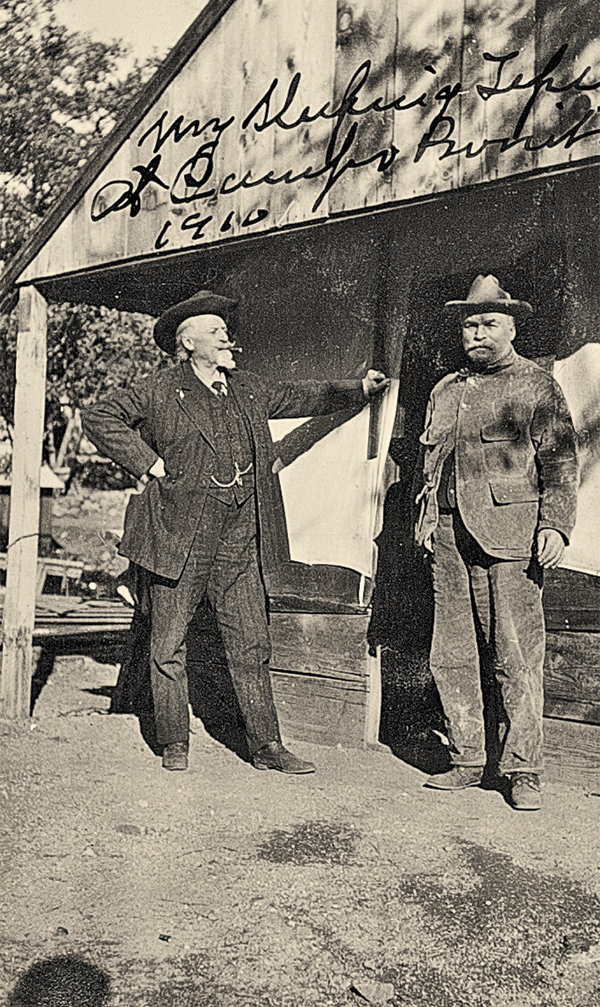

Nearly two decades would pass before Buffalo Bill decided Arizona may make a good home for him. Perhaps he dabbled in the territory’s mines before then, but the earliest notice of Buffalo Bill’s interest that historians have on record starts in 1905 or 1906, when Tucson resident and mining promoter John D. Burgess came calling at the showman’s ranch in North Platte, Nebraska, to tout his Campo Bonito mines in Oracle, and Buffalo Bill let his ear get bent.

“I’ll tell you, Bill, there’s a fortune down there for the man who has got the courage and foresight to invest,” Burgess promised Buffalo Bill.

When he asked if the mine were a sure thing, Burgess replied, “Sure as I am the sun’s goin’ to rise in the morning.”

If Col. Cody ever needed a sure thing, the time was now. By the winter of 1908, when he visited Oracle to inspect Burgess’s mines, success had started changing. He was facing continuing competition from Pawnee Bill’s Wild West and Great Far East Show. He sold a third interest in his own show to Pawnee Bill, and they created the “Two Bills Show,” which would go on to tour for five seasons before going bankrupt in 1913. In the midst of this was “sure-thing Burgess.”

But Buffalo Bill stayed skeptical enough to seek the advice of a friend in New York, L.W. Getchell, who had an extensive background in mining. In the fall of 1909, L.W. looked over Burgess’s Campo Bonito mining district and vouched for its possibilities. Buffalo Bill bought into the venture in 1910 and hired L.W. to manage it. L.W. brought his civil engineer son, Nobel, to help—a mistake that would haunt everyone.

Dreaming of Riches

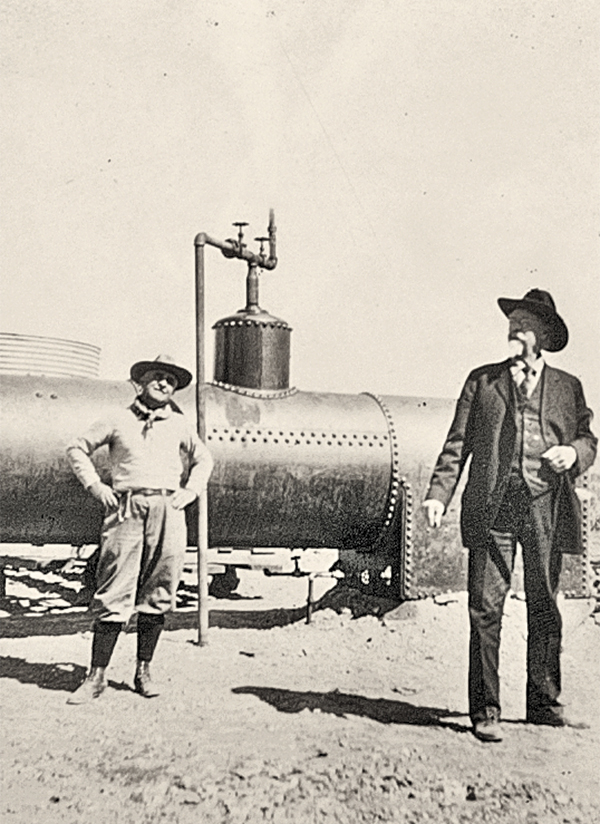

Mining began in the fall of 1910, and Buffalo Bill got a good-news-bad-news telegraph. “They say maybe we can take $3.5 million out of the mines if we put in the right machinery,” he told his secretary, Dan Muller. “The kicker is that they say the machinery will cost another $50,000. I’ll have to get someone else to invest. I can’t swing no $50,000 now.”

Somehow, Buffalo Bill found the money, which turned Campo Bonito’s six claims into a $600,000 corporation. After the show season ended in 1910, Buffalo Bill moved to Oracle for the winter to be near his mining claims. He was joined by his wife, Louisa, or “Lu Lu”—after they’d dropped plans for a much-discussed divorce.

Arizona Territory in general and Oracle in particular were thrilled to have the celebrated showman in their boundaries. The Codys stayed at the Mountain View Hotel owned by Annie and William Neal—a friend since the Indian campaigns. Lu Lu reportedly sat on the porch knitting, while Buffalo Bill sometimes shot at wooden blocks or threw out $10 gold pieces.

Locals were astonished to discover the couple had little regard for their own priceless articles. Local historian Elizabeth Lambert Wood noted in her Arizona Hoof Trails that she personally expressed concern to Lu Lu about the “valuable trophies that were tossed about, under everybody’s feet,” in particular, “The saddle that Queen Victoria gave the Colonel is lying there on its side on the ground. The embossed silver buffalo heads on it are worth a fortune.” Yet Lu Lu couldn’t be bothered with such “negligible trifles,” Wood added.

The Codys returned to their Oracle mines in the winter of 1911, as well. By then, Buffalo Bill had encouraged Col. Daniel Burns Dyer, a former Indian agent at Fort Reno, to join in his mining venture. Buffalo Bill reorganized his Campo Bonito company into the Cody-Dyer Arizona Mining & Milling Company. With the corporation’s $5 million capitalization, “every man in the company is already a millionaire in his own right,” the El Paso Herald reported on November 18.

If anyone was whispering in the Colonel’s ear that these mining claims were a folly, that person would have been his wife. She didn’t keep him from buying more and more, but Wood does credit Lu Lu with “saving more Cody friends from being poured into the losing venture.”

Buffalo Bill and his foster son, Johnny Baker, spent much of their time in the High Jinks cabin built at Campo Bonito. From there, they could see mining activities and dream of the riches to be hauled up from the earth. This was also where Buffalo Bill played Santa Claus to miners’ children, who believed he was the real thing.

But the riches never happened. Not only did the mines not produce, but Buffalo Bill was being robbed blind from officials he trusted. He learned Noble Getchell was skimming off every mine claim and every equipment purchase, and was greatly inflating the payroll with ghost employees. No one knows if the father knew of the son’s thievery, but Buffalo Bill sent both of them packing in March 1912.

Buffalo Bill’s mining experiences in Arizona were summed up in a document seeking designation of his High Jinks mine on the National Register of Historic Places: “High Jinks produced a few thousand dollars in gold. Buffalo Bill realized nothing on his half-million dollar investments at Camp Bonito and adjacent High Jinks.”

Go Big or Bust

With his mine of riches unrealized, Buffalo Bill seized on another possible avenue of income in the spring of 1911—the year before Arizona became the 48th state. Papers locally and nationally touted Col. Cody for the U.S. Senate, one reporting, “With a Senator on the floor able to snuff out a candle at forty paces, decorum could be preserved…without the services of a presiding officer.”

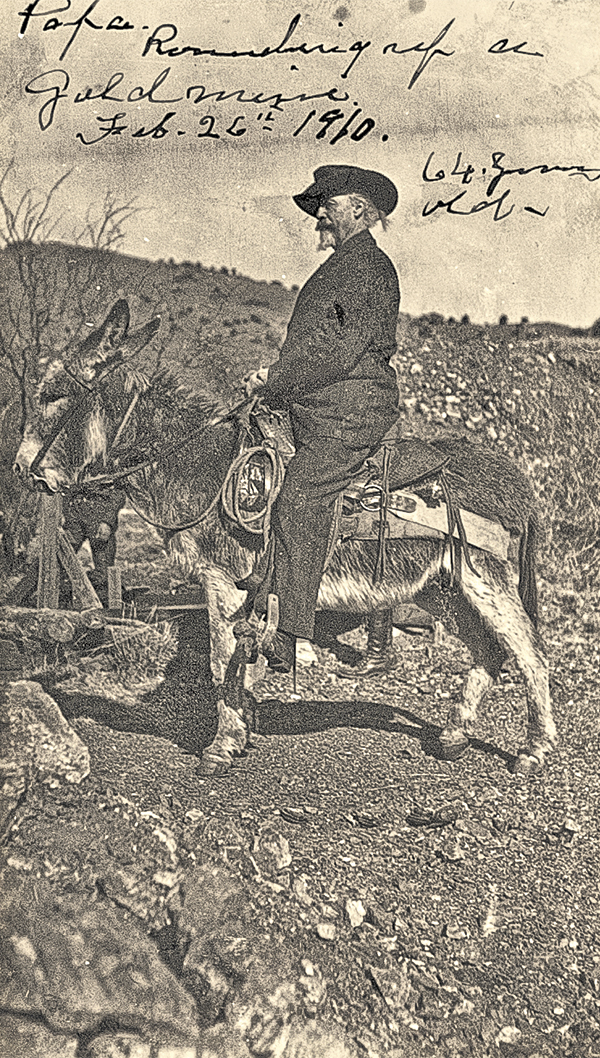

But alas, Buffalo Bill dropped the idea as impractical when he realized he needed to go back to work doing what he’d been doing since he founded Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in 1883. Then, he was a robust man of 37. Now, he was in his mid-60s, and he was tired, with a bad heart, failing kidneys and hair so thin he wore a toupee—although folks in Arizona Territory insisted his long white mane was really a wig.

Buffalo Bill’s last performance was on November 11, 1916, in Portsmouth, Virginia. He had abandoned his Arizona Territory mines—hoping at best to sell them, but finding no buyers—and planned to stay in Virginia for the winter. But on a trip to visit his sister in Denver, Colorado, his health gave out; he died at 70 on January 10, 1917.

“Let my show go on,” were his reported last words.

At the time of his death, he’d thrown away the equivalent of $12.5 million on worthless mines in Arizona Territory and had roughly $100,000 left—a reasonable sum, worth $1.9 million in today’s money, but still a trickle of his once great fortune.

“So he never struck gold in this Oracle soil,” Dr. Paul Fees, former curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum, said at the 1997 dedication of High Jinks as a National Historic Site. “I’m told there are only traces here in any case. But we all know that with his fame undiminished, his faith in the West vindicated and his reputation as a visionary resurgent, Cody found his gold mine in the sky.”

Jana Bommersbach thanks Jeremy Johnston, the curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody, Wyoming, for his assistance in researching this article. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.