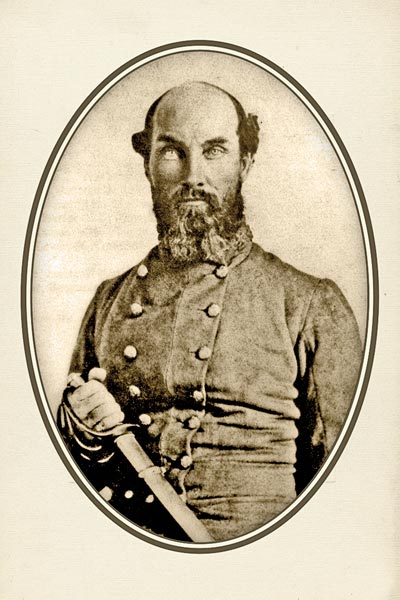

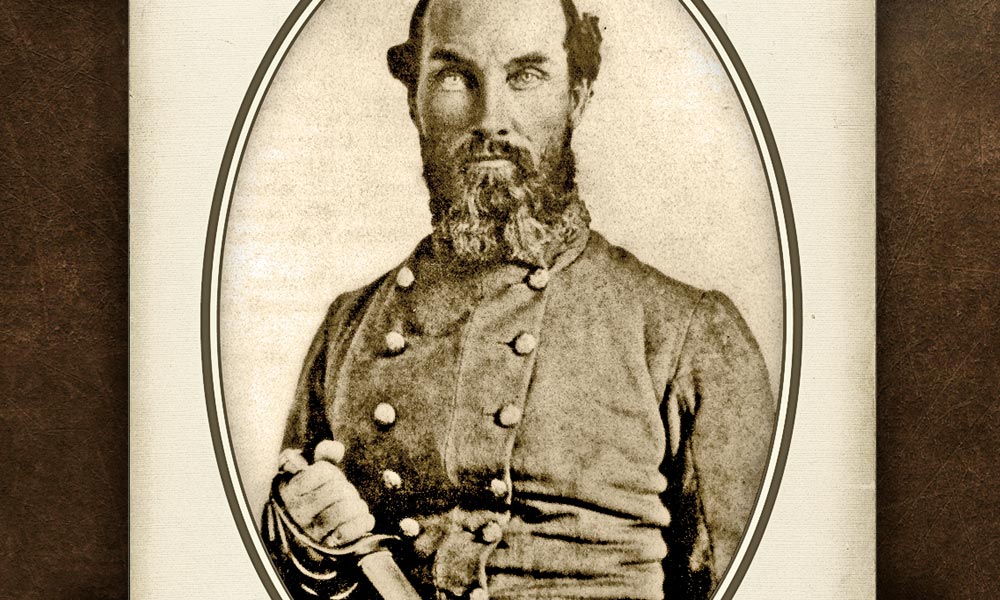

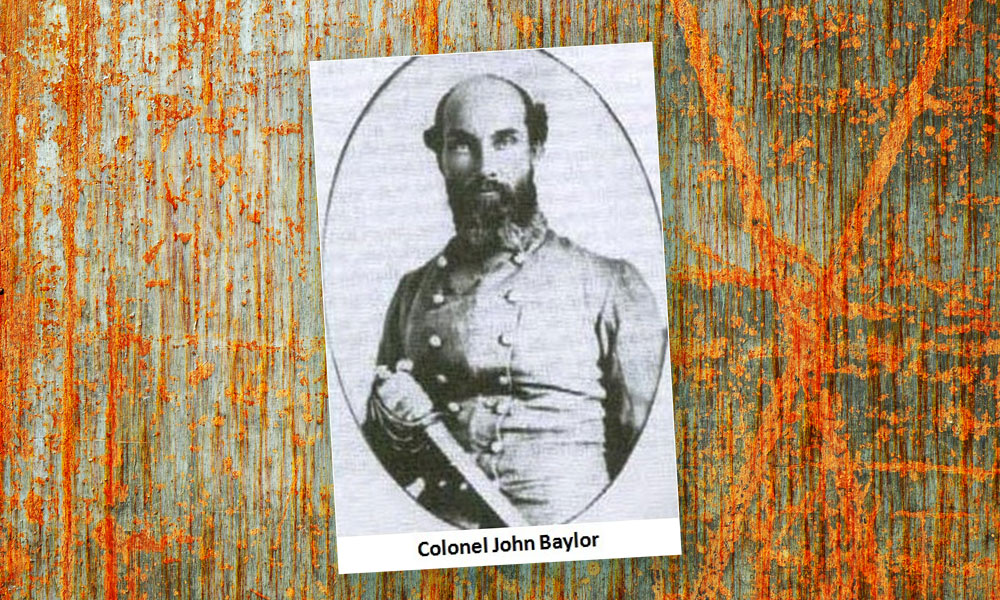

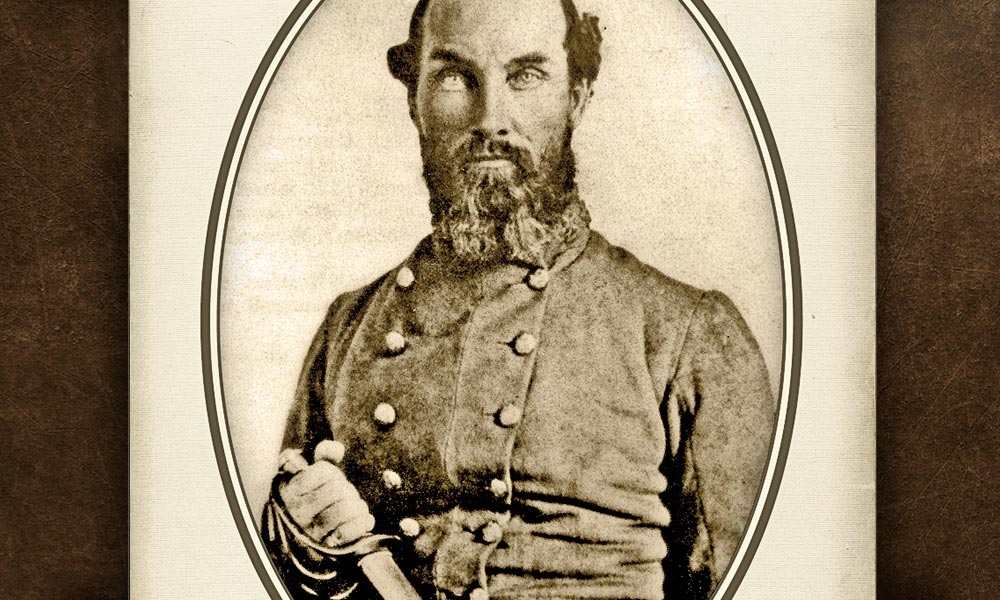

John Robert Baylor was an ambitious man, one who wanted position and power and recognition. He had shown that many times over between his move to Texas around 1835 and the start of the Civil War.

The war gave him a chance to further his ambition. In 1861, Baylor became a Confederate lieutenant colonel and took over the Second Texas Mounted Rifles.

On July 24, three days before his 39th birthday, he led roughly 300 men from Fort Bliss in an effort to take Fort Fillmore, just outside Mesilla, New Mexico. One of his soldiers, however, turned traitor and warned the Union commander. Baylor, being flexible, changed his plan and entered Mesilla on the afternoon of July 25. Pro-Confederate citizens welcomed the troops.

His easy victory did not last long. Union Maj. Isaac Lynde, based at the fort, immediately marched 380 men, along with howitzers, to Mesilla and ordered Baylor to give up. Baylor refused.

The Union artillery opened up on the rebels, then Lynde led a charge on the town. It was a disaster; at least three bluecoats died and several were hurt before the major and company retreated to the fort.

Baylor then went on the offensive, calling up reinforcements and artillery from El Paso, Texas. Lynde caught wind of that news and decided the best course of action was to run. He and his men abandoned Fort Fillmore and headed northeast through the Organ Mountains. Baylor discovered the retreat in the early morning of July 27 and gave chase—with troops and some civilians from Mesilla, New Mexico.

Within a few hours, the Confederates caught up with the stragglers, many of whom were suffering from dehydration in the blazing summer heat. Lynde had set up a temporary camp a few miles away. Baylor and some riders charged into the totally unprepared camp.

Despite having nearly 500 men at hand, far more than the Confederate force, Lynde surrendered. The First Battle of Mesilla was a resounding Confederate victory and one of the few Civil War “battles” fought in the Southwest.

Baylor basked in his new status as hero. Probably a bit too much. He proclaimed the entire region west of Texas as Arizona Territory for the Confederate States of America. He naturally named himself governor, a status agreed upon by officials in the rebel capital of Richmond, Virginia. Baylor did not hold the job long. He was about to learn a hard lesson about pride that fed his notion he could do anything he wanted.

In December, Baylor fatally shot The Mesilla Times Editor Robert Kelley, who had criticized some of the governor’s decisions. Kelley was a strong Southern sympathizer, so Baylor’s shine lost a fair amount of luster—especially after the territorial attorney general, appointed by Baylor, pardoned him for the killing.

Baylor then turned his attention to another enemy—Indians, specifically Apaches. He had long hated Indians, once owning and editing a Texas newspaper called The White Man. The Apaches had been a nuisance in New Mexico and Arizona, and Baylor decided to take care of the problem; in March 1862, he sent out a letter ordering the extermination of the tribes. That was the final straw for Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who fired Baylor and took away his commission.

Baylor rejoined the Confederate States Army as a private, but he was not present for the Second Battle of Mesilla, when the Union proved victorious, on July 1, 1862. Baylor never again gained the heights he had reached in 1861.