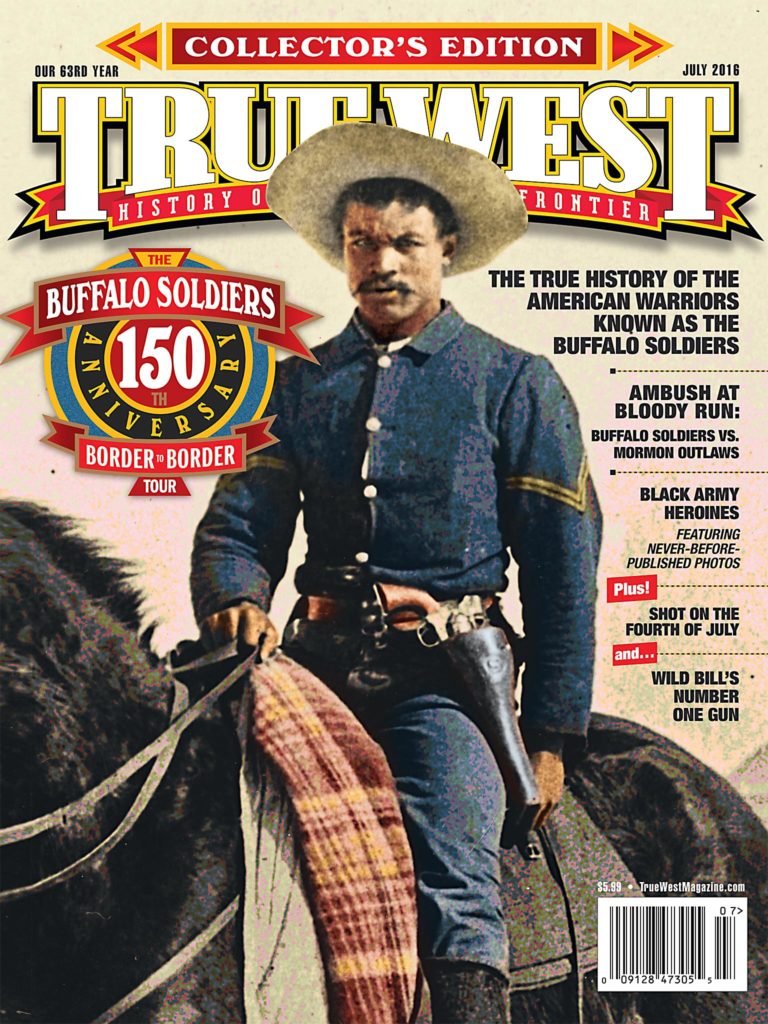

United States Army Paymaster Maj. Joseph Washington Wham (rhymes with bomb) is riding in a dougherty (canopied ambulance) on his way to pay “all troops in the muster of April 30,” which includes all the soldiers at Arizona’s Forts Hauchuca, Bowie, Grant, Thomas and Apache, and San Carlos.

Having successfully paid the troopers at Forts Bowie and Grant, Wham and his Buffalo Soldier escort are on their way to Fort Thomas, around the mountain from Fort Grant.

Private Hamilton Lewis drives Maj. Wham’s lead wagon, carrying Wham, his clerk William Gibbon, mule tender Pvt. Caldwell and Sgt. Benjamin Brown, as well as a strongbox full of mostly gold coins, valued at just over $28,000. A second wagon follows Wham’s with an armed escort of 10 Buffalo Soldiers stationed at Fort Grant.

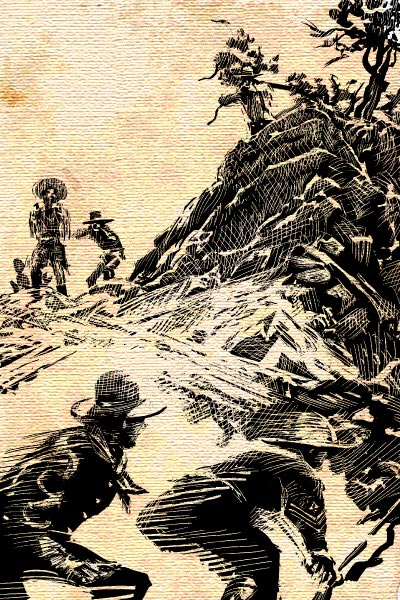

As both wagons enter a narrow defile known as Bloody Run (named for an Apache attack on this spot seven years earlier), the driver of the advance wagon spies a good sized boulder in the center of the road.

Gibbon and several soldiers get out to investigate. As they walk forward, one of them remarks, “That rock was rolled there by hand.”

Gibbon reaches down to throw a smaller rock off the road when a voice is heard from above: “Look out, you black sons of bitches!”

The outlaw, dressed in buckskin, fires his pistols, a signal that unleashes a volley of rifle fire from the ridge, bringing down the lead mule on Wham’s wagon and two mules on the escort wagon. The soldiers retrieve their rifles (stored unloaded in the bed of the second wagon) as the terrified mules buck and pull at their traces, dragging both wagons off the road and into the rocks.

Rifles fire from both sides of the road as Maj. Wham directs his troops to find cover. Multiple shooters rain bullets down at the exposed troopers: Pvt. Lewis takes a bullet in the gut; Pvt. Squire Williams is hit in the ankle; and Sgt. Brown is struck in the arm and side.

The troopers take up a position behind a small ledge, but the attackers command the heights and rain a withering fire at them, striking several more troopers. Finally, several of the soldiers begin to fire back, but they can’t hold the position and retreat down a ravine draining into Cottonwood Wash. Major Wham joins them as they are driven to the creek bottom, about 300 yards from the wagons. With wounded troopers lying all around him, Wham has given up defending the payroll.

Several robbers come down from the fortifications and climb into Wham’s wagon. The troopers hear violent hammering (they can’t see the wagon). The soldiers count 12 to 15 men making their way back up and over the ridge where the attack commenced. The fight has lasted about two hours, but the attackers have achieved their goal—the payroll is gone.

Not Everyone Fights

Private Caldwell (recently discharged and hitching a ride) runs for it. “He uses his limbs pretty swift for an old man,” Frankie Campbell remarks about Caldwell at the trial. Private Fox takes cover behind the ledge, but doesn’t fire back at the robbers. One of the folk tales of the fight is that Campbell placed a shawl around Fox’s neck and told him not to remove it, and Fox’s life is spared because of it.

The Man with the Plan

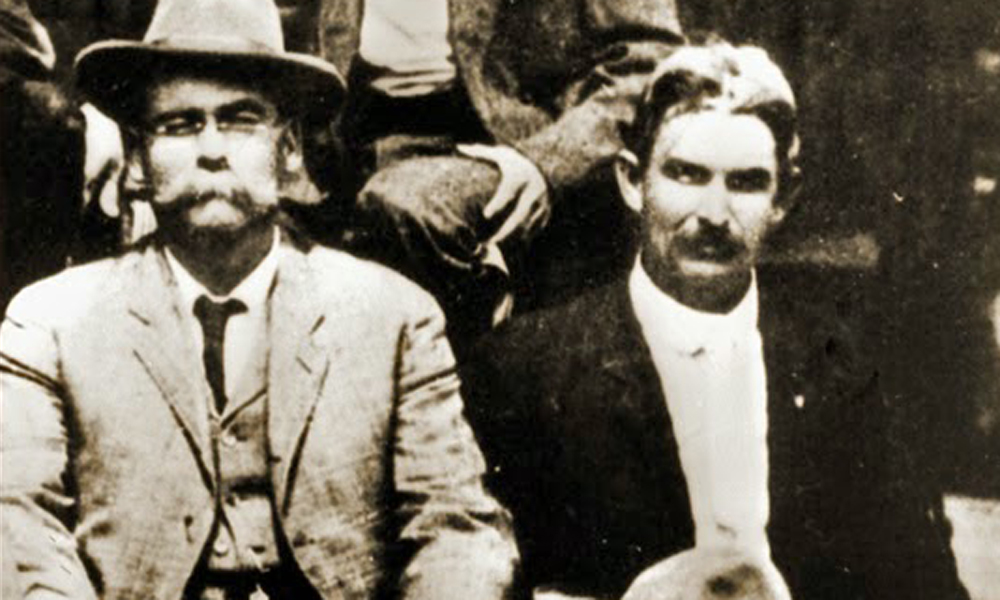

Gilbert Webb, 52, served his Mormon mission in Hawaii, had three wives in Utah, got crossways with Brigham Young after failing to deliver on a contract to supply telegraph poles, declared bankruptcy and skated on the intervention of his attractive sister, Ann Eliza, who agreed to marry Young in exchange for retiring her brother’s debt.

Webb moved to Arizona to help grade track for the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad and later landed in the Gila River community of Pima where he started several businesses, including a store, a real estate operation, a stage line from Solomonville to the rail head at Willcox and the Webb Cattle Company. He also served on the town’s first city council and as mayor, and helped build Pima’s first school.

A year prior to the robbery, Webb’s name was struck from the Pima Mormon rolls for his alleged illicit affair with a widow (although he still chaired the church’s building committee). At the time of the robbery, Webb was on the verge of bankruptcy; his stage line and his store had been shut down, and he didn’t have the capital to fulfill several lucrative government contracts. Many people in town owed him money. The need for capital was clear, and the means was on its way—being carried by Wham’s wagon.

Righteous Robbers

By most accounts, the Wham Payroll Robbery is almost a community project, led by Pima’s mayor and major job provider Gilbert Webb, who convinces most of the cowboys and farmers to participate by pinning the survival of the town (and, by extension, his fellow Mormon citizens) on liberating U.S. funds. It isn’t a hard sell because the U.S. government has been harassing Mormons for a long time. The gang of 12-15 includes Webb’s three sons: Wilfred (who, at the time of the holdup, is facing an indictment for stealing cattle), Leslie and Milo.

The robbers do not wear masks, probably because masks would imply wrongdoing. They likely rationalize that the black troopers are cursed and unworthy of the money. At that time, a virulent strain of Mormonism, tracking back to leader Brigham Young, contends that blacks are descendants from Noah’s son Ham, who was cursed by God, and that his descendants’ dark-colored skin is the “mark of Ham” (many who believe this also apply it to Indians). By liberating much needed capital for the work of God, from an evil government protected by descendants of Ham, the robbers may not have felt the need to wear masks.

A local quote from that time says it all: “The nigger soldiers would just waste the money on liquor, gambling, and whores, so why not take it and use it to the benefit of a community that really needed some cash to stave off bankruptcy for Webb and some of his neighbors.”

A Pima pioneer, Don Pace, later claims that the “Pima colony would have been starved out if not for the ingenuity of Gilbert Webb.”

The Eyewitness in the Bright Yellow Blouse

Riding a big bay, Frankie Campbell, a.k.a. Frankie Stratton, is decked out in a bright yellow, tight-waisted blouse, a billowing wine-colored skirt and a large floppy straw hat decorated with a red paper rose and red velvet streamers.

Her husband is locked up in the Fort Grant guardhouse, accused of killing a fellow soldier. The couple are known gamblers (some speculate Frankie is a soiled dove), and they have at least one child. Frankie insists on riding with the paymaster entourage to Fort Thomas to collect on gambling debts on payday.

Riding just ahead of the wagons, Frankie is beyond the boulder when the shooting starts and startles her horse, who throws her off. She takes cover under a bush, near the fork in the road leading to Cottonwood Creek, and witnesses the battle with a ringside seat. After the robbers leave, she approaches the troops. Major Wham arrests her on suspicion of being in collusion with the outlaws. She is left behind with the severely wounded while Wham commandeers the escort and heads for Fort Thomas.

At the subsequent trial, Frankie keeps the jurors in stitches with her humorous responses.

The Suspects

William Ellison Beck, a.k.a. “Cyclone Bill,” a former Texan with a bad leg (jokesters claim he stands “5’6″ on one foot and 6’2″ on the other”); arrested in a Clifton saloon on May 15. Bill got his nickname after absconding with a Yuma freight wagon. When cornered in Tucson, he claimed a desert cyclone swept up him and the wagon and dropped them both in the Old Pueblo. Cochise County Sheriff Texas John Slaughter recently ran him out of Tombstone.

Marcus E. Cunningham, a.k.a. “Bull Baron of the Bonita,” a New Yorker who came to Arizona to work on the Southern Pacific railroad; arrested at Fort Thomas by Deputy Marshal Billy Breakenridge and others on May 16. Marcus ran a saloon and butcher shop in Maxey, worked as a ranch foreman and served as election inspector and deputy sheriff. He also campaigned unsuccessfully as the democratic nominee for sheriff in 1888.

Lyman Follett, a rancher previously arrested with Cunningham for stealing government livestock; arrested on May 20. During the fight, one of the robbers was wounded in the hand; after the robbery, Lyman had an injured hand. Four days later, his three brothers, Warren (Wall), Joseph Edward (Ed) and William, were held at the Fort Thomas guardhouse (William was released on May 27 for lack of evidence).

Wilfred Webb, a rancher; arrested on May 24 as he drove his wagon up to his home in Pima. Wilfred’s father, Gilbert, was in Tucson at the time, allegedly on business, but he aroused suspicion by helping Cunningham make bail. Gilbert was arrested on June 2, at the San Xavier Hotel, next to the train station, for “meddling with federal prisoners and witnesses.”

David Mayer Rogers, a cowhand for the Webb Cattle Company, gave himself up at Fort Thomas on May 25, the same day Sebird H. “Bud” Henderson, a Pima farmer and friend of the Folletts, was arrested by a 10th Cavalry detachment in Globe. The next day, another cowhand who worked for Webb, Thomas Norman Lamb, was served papers at his home in Matthewsville.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

After a marathon trial in Tucson, Arizona, involving major politics and infighting (the original judge was removed), all seven defendants were acquitted. Even though an all-white jury exonerated the accused men, local kids yelled epithets at the men (“Damn Mormon Robbers!”) when they boarded the train for home.

Gilbert Webb allegedly took most of the money from the robbery to pay off his massive debts, forgive debts to fellow Pimans (especially those who helped pull off the robbery) and pay for the attorneys. The next year, Webb was elected a delegate to the Territorial Democratic Convention, but then he was indicted for defrauding the Pima school district of $160. He left Pima in 1891 and ended up taking a railroad job in New Mexico. Eventually moving to Colonia Juárez, Mexico, he died and was buried there in 1923—a year after the Mormon Church had reinstated him.

Medal of Honor recipients Benjamin Brown and Isaiah Mays stayed in the U.S. Army, with Brown retiring in 1904 and dying six years later. Suffering from rheumatism, Mays resigned from the Army in 1893 and spent the rest of his life around Bonita, just outside Fort Grant. He tried for years to get an Army pension, but failed, dying at Phoenix’s Arizona State Hospital in 1925. (Buried in the hospital’s cemetery, his body was rediscovered in the late 1960s and a proper headstone was erected.)

Gilbert Webb’s attractive sister, Ann Eliza, who got him out of hot water in Salt Lake, divorced Brigham Young in 1875 and gained nationwide notoriety as the author of Wife No. 19, or the Story of a Life in Bondage.

Recommended: Ambush at Bloody Run: The Wham Paymaster Robbery of 1889 by Larry D. Ball, published by Arizona Historical Society.