Follow the Northern Cheyennes’ desperate and deadly dash for home from Oklahoma to Montana.

The hot August 1878 weather bore down at Darlington Agency near Fort Reno in central Indian Territory. Northern Cheyenne leader Dull Knife and his followers had been harassed and pushed around since the attack on their camp on November 25, 1876. After being removed to Indian Territory and Darlington, they faced limits on hunting. There were few buffalos, and a shortage of rations provided by the federal government meant many were hungry. The area was a hellhole. Hot, sultry air combined with disease and starvation to decimate the Indians. By September 1878, fewer than 350 had survived.

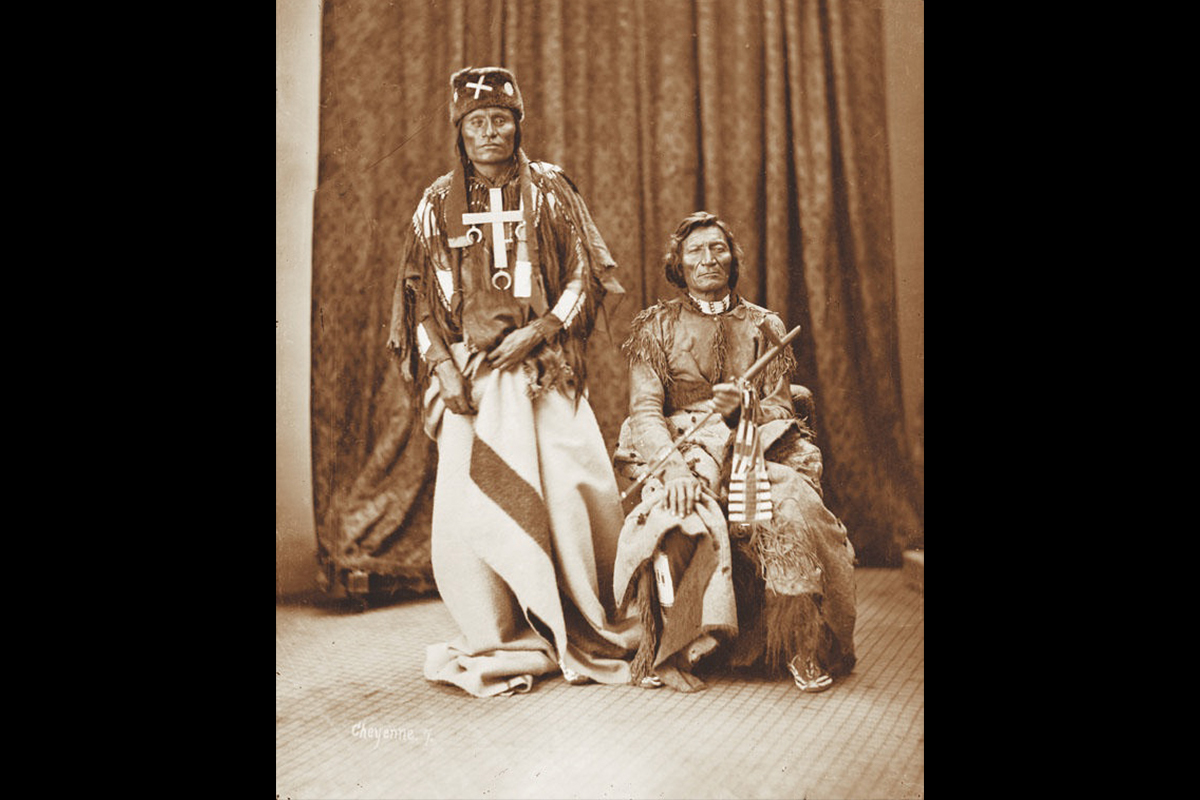

In addition to Dull Knife, Little Wolf, Old Crow and Wild Hog were leaders of these Northern Cheyennes. They did what they could to improve conditions for the people, but discontent grew, and by early September, the tribal members had abandoned their camps at Darlington. They were going home, back to tribal ranges in South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana territories.

Their 750-mile, 44-day trek took them across western Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. Along the way they engaged in attacks and raids on settlers as federal troops quickly amassed and set off in pursuit.

By the time the soldiers reached the Cimarron River, not far from the present town of Freedom, Oklahoma, the Indian women and families were far ahead, but many of the Indian men remained in the region, watching the soldiers as they came after the tribe.

The Cheyenne men finally faced off with the pursuing 4th Cavalry and a number of Indian scouts, many of whom were also Cheyennes. When the scouts told Little Wolf and the people with him to return to Indian Territory, Curly Hair, one of the men with Little Wolf, said: “Go back and tell them we are going home. We don’t want any fighting. If the Army wants to fight us they can. We are not going back.”

The melee that followed started when an Arapaho scout with the soldiers noticed one of his horses being ridden by a Northern Cheyenne man. He took a pistol from a solider and raced toward the Cheyenne tribesmen. This led to the Battle of Turkey Springs on September 13 and 14 and the killing of 20 soldiers, plus the wounding or killing of many horses. The Northern Cheyennes left the battlefield victorious. Following their families, they rode north across western Kansas.

Some troops had organized at Sidney Barracks in Nebraska shortly after the Indian breakout. Located on the Union Pacific Railroad line, Sidney Barracks had access to trains that could carry soldiers east or west to intercept the Cheyennes, should they make it that far north. Maj. Thomas Tipton Thornburgh of the 4th Infantry responded but failed to stop the Cheyennes who crossed the railroad just east of Ogalalla, Nebraska, and then disappeared into the Sand Hills.

Now back in Nebraska, but with troops closing in from various directions, the Indians split their ranks. Little Wolf and his band headed toward the Powder River and eventually reached Montana Territory. Dull Knife, Wild Hog, Old Crow and their followers turned toward the old Red Cloud Agency, near Camp Robinson, expecting to find sanctuary with Red Cloud and other Lakotas. They did not know that the agency had been moved and was now situated along the Missouri River.

Troops with Maj. Caleb H. Carlton’s 3rd Cavalry based at Camp Robinson set out looking for the fleeing Indians, and in a foggy accident on October 25, stumbled onto the camp of Dull Knife and Wild Hog. Following tense negotiations, the Indians were taken into custody and moved to Camp Robinson, where they were held in an abandoned barracks.

Sgt. Carter P. Johnson was with the troops and later told Indian Wars historian Walter Camp that “Dull Knife said his people were hungry & if we would give them something to eat they would follow. We set out some rations & the Indians took them & followed us. This was about 10 a.m. We went down into the valley & camped that night on Chadron creek. Dull Knife’s band camped in the creek bottom and we had only 2 companies at that time camped on both banks right over them.”

Buffalo Hump was with Dull Knife and also later told Camp about the Cheyennes’ surrender: “When Dull Knife surrendered there was no firing on the part of either soldiers or [Indians]…. When they surrendered most of them gave up their arms, but a few concealed them under their clothing and in this way retained possession.”

In December 1878, Camp Robinson was renamed Fort Robinson and by January 3, 1879, the Cheyennes were crammed into a log barracks at the post. In the early days of the Indians’ incarceration, soldiers prepared food for them. The women and children were allowed to go outside the barracks freely, and the men were permitted to be outside with supervision. “The Indians were pleasant and agreeable to their guards inside and often talked and smoked with us in the little room. They had their dogs with them in the barracks and a heating stove, and were comfortable enough,” Johnson said.

The atmosphere changed when orders came to once again remove the Cheyennes to Indian Territory. The tribespeople made it clear that they would die first. When negotiations with the headmen failed, Capt. Henry W. Wessells removed leaders Wild Hog and Old Crow from the barracks and cut off food, water and fuel supplies to the people remaining inside. Lacking basic supplies, the Indians “now became very ugly to the inside guards, having changed their demeanor completely, and were getting to be very unruly,” Johnson said.

The troops were on heightened alert while the Indians reportedly sang and danced, tore up the floorboards, and barricaded the windows. After dark on January 9, 1879, the Cheyennes were quiet, according to Sergeant Johnson, who said, “I declared then and there that they were getting ready to come out.” Upon hearing the first gunshot later that evening, the sergeant ordered his men toward the fort. “We double-quicked to the fort, over a mile away, not waiting even to fully dress.”

Buffalo Hump recalled, “When it became evident that the soldiers intended to starve us to death we thought we might as well die fighting as to starve so it was decided to break out.” He described the action: “The soldiers had boarded up their windows of the guard house & built a fence around the house a little way from it and guards were patrolling outside the fence. When the time came to [break] out I busted the boards from the window and was first out and knocked a hole through the fence with an ax. A fight started right there.”

Once outside the barracks, Buffalo Hump joined his mother and sister, Dull Knife, and other members of the band. “We were out 10 days without anything to eat and we nearly perished,” he recalled. Eventually some of the 149 Northern Cheyennes who had escaped found refuge with the Lakotas at Pine Ridge. More than 30 Indians were killed and another 30 were wounded during the escape from Fort Robinson. Eleven members of the 3rd Cavalry died, and 10 were wounded.

The outbreak from Fort Robinson is recognized every year with the Fort Robinson Outbreak Spiritual 400-mile run for young people who leave the barracks where their ancestors were imprisoned on the actual day and time that the outbreak happened in 1879 (January 9, 10:30 p.m.). They run from Fort Robinson north through the Black Hills into Montana, and across the Northern Cheyenne Reservation along Highway 212, which is designated the Warriors Trail for the number of historical sites in the area. The runners end their ceremonial trek at a hilltop burial ground in Busby, Montana, where more than two dozen men, women and children killed during the outbreak are buried.

First started to honor ancestors, now the run centers on healing and wellness, cultural and language preservation and other social issues important to the Northern Cheyenne people.

A Wide Spot in the Road

301 River Rd, Harrison, NE 69346

Courtesy Nebraska Tourism

Agate Fossil Beds National Historic Site

Rancher James Cook established a friendly and longstanding relationship with the Lakotas and Northern Cheyennes at his ranch in western Nebraska. Through the years the people gifted him with items ranging from buckskin suits made for his sons, to gloves, a hide painting of the Battle of the Greasy Grass, pipe bags from Red Cloud’s family and more. These items are now part of the Cook Collection at Agate Fossil Beds National Historic Site, which includes rare and unique Northern Plains material goods including shields, moccasins, large and small bags and much more. The site is located midway between Mitchell and Harrison, Nebraska, off State Highway 29; it is also accessible from Highway 71 north of Scottsbluff.

Good Eats and Sleeps

Good Grub: Swadley’s Bar-B-Q, El Reno, OK; The Silver Dollar Bar & Grill, Sidney, NE; Front Street Steakhouse & Crystal Palace Saloon, Ogallala, NE; Buffalo Dreamer, Hot Springs, SD; Maggie’s Café, Ashland, MT

Good Lodging: Hampton Inn, El Reno, OK; Fort Robinson State Park Lodge & Campground, Crawford, SD; Sylvan Lake Lodge, Custer, SD