Her smile could be shy; her glance at times demure, but her ears never missed a secret. A master of disguises, she changed her accent at will, infiltrated social gatherings and collected information no man was able to obtain. She cried on command, yet was stoic while interrogating a suspect. She never, ever slept on the job. She was a detective working for the nation’s first security service—the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Allan Pinkerton, founder of the organization and pioneer in the field, had dared to hire women as agents.

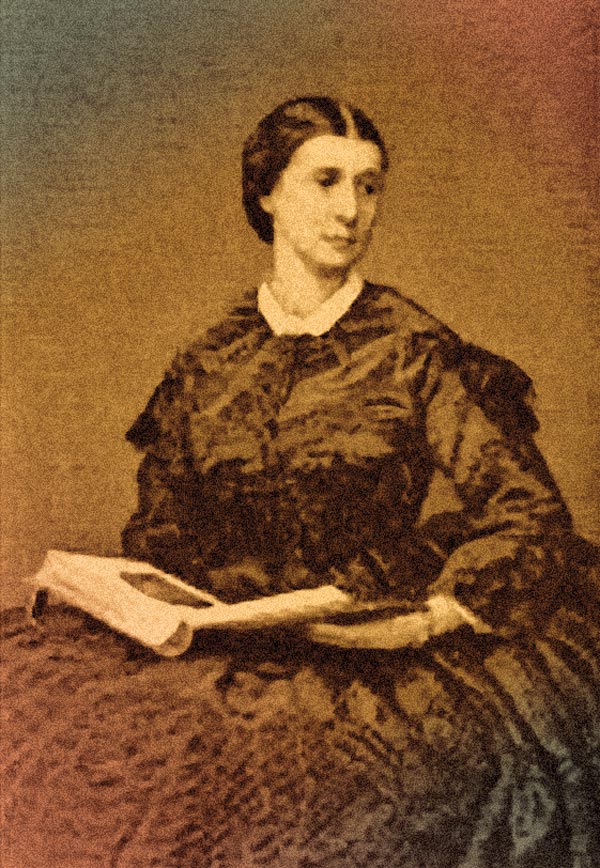

Recognized by many historians as America’s first female detective, Kate Warne persuaded Pinkerton to take a chance on her sleuthing skills in 1856. Prior to her being hired at the agency, the company’s only female employees fulfilled secretarial duties.

Born on August 25, 1819, in Glasgow, a port city in Scotland, Pinkerton followed the trade of a cooper until the age of 33. Ending up in the Chicago area, he uncovered a ring of counterfeiters. The fame of catching those criminals, together with his success in capturing horse thieves, gave Pinkerton a wide, local reputation; he was made deputy sheriff of Kane County, in which capacity he became the terror of cattle thieves, horse thieves, counterfeiters and mail robbers all over Illinois. The born detective leapt out of obscurity, parlaying his talent into a company he established in 1850. His excellent instinct for selecting the right people to work for him extended to Warne, who proved herself to be one of his finest agents.

Over the course of Warne’s 12-year career as an agent, she assumed numerous aliases. In her various months-long stints undercover, in roles that ranged from a benevolent neighbor to an eccentric fortune teller, Warne, just as the other female investigators did, willingly put herself in harm’s way to resolve a case. Whether they were searching the home of a suspected murderer for clues or transporting classified material past armed soldiers, Lady Pinkerton agents, or Pinks, demonstrated they were fearless and capable.

After a little more than four years, Warne had so impressed Pinkerton with her aptitude for investigation and observation that he made her the head of all the female detectives at the agency. In 1861, he placed her in charge of the Union Intelligence Service, a forerunner of our nation’s Secret Service. The function of the agency was to obtain information about the Confederacy’s resources and plans, and to prevent said news from reaching the Rebel army. Warne and the other lady operatives excelled at this duty.

– Courtesy Chris Enss –

Warne had come by her job at the Pinkerton National Detective Agency when she walked in off the street, introduced herself and suggested Pinkerton hire her, not as a secretary, but as a detective.

“Women could be most useful in worming out secrets in many places which would be impossible for a male detective,” Warne told Pinkerton, as he recalled years later in his memoirs.

The idea of a female detective intrigued him, and he hired her. One of the most important cases she worked on while employed with the company involved President-elect Abraham Lincoln. After a plot to assassinate the politician was discovered, Warne helped secret the future president to Washington, D.C. for the inauguration into office.

The Mixed-Race Agent

Hattie Lewis, another notable Pinkerton agent, was hired in 1860. She was not only the second woman employed at the world-famous detective agency, but historians believe she was also the agency’s first mixed-race female employee.

Pinkerton looked beyond gender and race, as few did at the time. In the late 1840s, he had been active on the Underground Railroad and helped many runaway slaves escape to Canada. He spoke out against the Fugitive Slave Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in September 1850, which penalized officials who did not arrest an alleged runaway slave and subjected them to a fine of $1,000. Since suspected fugitive slaves were ineligible for a trial, and therefore could not defend themselves against accusations, the law resulted in the kidnapping and conscription of free blacks into slavery.

Chicago became a clearinghouse for runaway slaves. In the rural area of Dundee where Pinkerton resided, some enterprising young men hunted fugitive slaves for the rewards. Outraged by these “blood hounds,” Pinkerton sought ways to defy them. In 1857, he was a member of a delegation called on to investigate a slave catcher passing through town. This investigation may have been where he met Lawton. Some of her family was suspected of being among a party of slaves Pinkerton sheltered to disperse to Canada.

Born in 1837, Lawton, a widow, was described by Pinkerton as “delicate and driven.” He wrote that “her complexion was fresh and rose-like in the morning. Her hair fell in flowing tresses. She appeared careless and entirely at ease, but a close observer would have noticed a compression of the small lips, and a fixedness in the sparkling eyes that told of a purpose to be accomplished.”

Lawton played a key role at the detective agency for many years, assuming various identities and ferreting out information that aided in solving numerous cases. (Her years of service are unclear because the majority of Pinkerton records were destroyed in a fire in Chicago in 1931.) In one of her most dangerous assignments, she gathered intelligence about Confederate troop movements. In 1862, Lawton and Pinkerton operative Timothy W. Webster were dispatched to Richmond, Virginia, posing as a wealthy married couple. Their primary objective was to gain acceptance from Southern sympathizers in the area and learn their plans to thwart the Union’s military efforts.

The “Genteel Woman Agent”

In late 1861, Pinkerton sent another eager female detective, Elizabeth H. Baker, to the Confederate capital to acquire information about the Rebel navy. Baker had been working as an operative for Pinkerton’s detective agency since late 1857, sometimes traveling outside of Chicago to team with other agents on robbery and missing person cases.

Prior to moving to the Midwest, she had lived in Virginia, so she was well acquainted with the customs and the people of the region. Pinkerton called her a “genteel woman agent,” and when the Civil War broke out, he considered her a “more than suitable” candidate for the assignment.

Baker not only managed to finagle an invitation to the home of a Confederate Navy officer and his wife living in Richmond, but also an invitation to a demonstration of Rebel submarine vessels equipped with torpedoes. Baker sketched all she had seen during the demonstration of the submarine, Merrimack, designed to battle against Union blockade ships, which included a drawing of the submarine and the people it took to man the vessel.

The Navy Spy

While Baker monitored the Merrimack’s military capabilities, another operative was acquiring a set of the submarine plans.

During her employment as a seamstress and housekeeper for a Rebel engineer who was restoring the steam-powered frigate, free slave Mary Touvestre (or Louvestre) overheard the engineer discussing the importance of the vessel as a weapon against the Union. She offered this information to her country and came to meet Pinkerton through the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles.

Since the engineer brought the plans for the ship home with him nightly, Touvestre plotted to steal the plans and turn them over to Union forces. In late September 1861, she sewed the vital information into the hem of her dress.

She set out, on foot, from Portsmith, Virginia, to the nation’s capital on a nearly 200-mile journey. Secreting the plans out of Virginia past enemy lines was difficult enough, but gaining an audience with a high-ranking military official also proved challenging; Touvestre had to talk her way around members of Secretary Welles’s staff in order to see him.

When she finally spoke with Welles, she explained her mission and presented him with the plans for the vessel. The secretary commended her bravery and dedication to her country; had she been captured by the Confederates, they surely would have killed her.

– True West Archives –

The Southern Belle

Elizabeth Van Lew masqueraded as a nurse at the Libby Prison near Richmond, Virginia, but in truth, the Southern belle was one of Pinkerton’s agents.

Federal prisoners in and out of the hospital furnished Van Lew with information vital to the North’s fight against the South. From the multi-windowed prison, they accurately estimated the strength of the passing troops and supply trains, and the destinations they were headed when they left town. They shared with her conversations about planned attacks and casualties that they overheard between surgeons, orderlies and guards. Van Lew dispatched the coded communication to secret service officials in Washington, D.C.

Loyal to His Pinks

Time and time again, the Lady Pinks proved their value to the agency. “It has been my principle to use females for the detection of crime where it has been useful and necessary,” Pinkerton noted in his memoirs. “…I intend to still use females whenever it can be done judiciously. I must do it or sacrifice my theory, practice and truth. I think I am right and if that is the case, female detectives must be allowed in my agency.”

Pinkerton was loyal to the women in his employ. The first one, Warne, inspired his company’s slogan, in 1861. While on assignment to protect President-elect Lincoln, Warne refused to close her eyes and rest until the politician was out of danger. Thus was born, “We Never Sleep,” scrawled below an all-seeing eye.

Although women were not admitted to any of America’s police forces until 1891 nor widely accepted as detectives until 1903, Warne and the Lady Pinks she trained paved the way for future female officers and investigators, and are regarded as trailblazers in the private eye industry.

Chris Enss is a New York Times bestselling author who has written more than 20 books about women in the Old West. Her latest book, The Pinks: The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, will be published by TwoDot in June 2017.