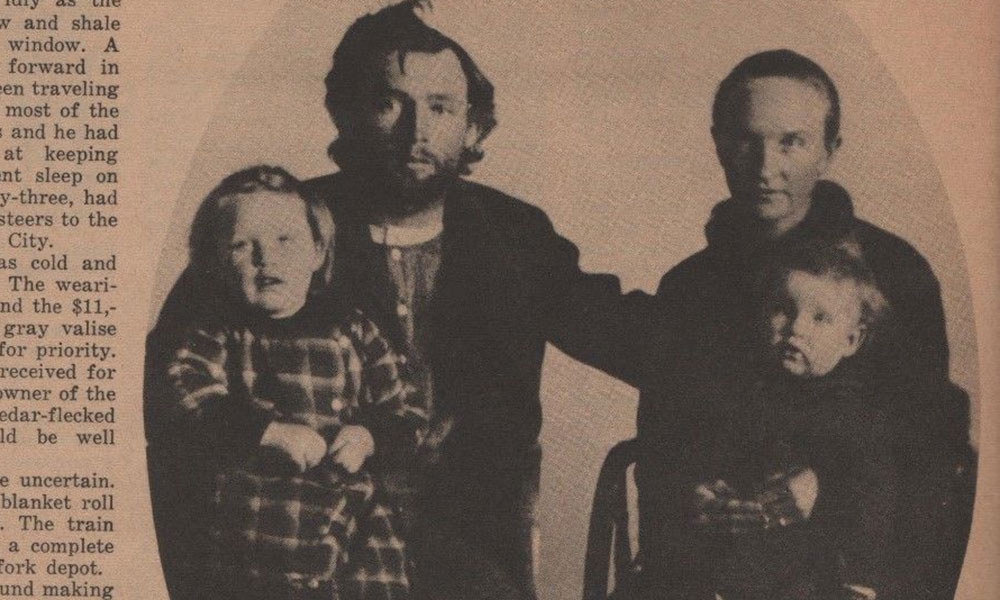

— Courtesy Abe Hays Collection —

On May 5, 1871, Sgt. John Mott and three others followed Apache footprints, tracking what they thought were the incautious wanderings of an inattentive Apache woman and her mount toward an unsuspecting ranchería. The rocky fringe of the mountainous heights and the boulder-strewn canyon lay before them. These did not register as warning signs because this was a few years before the U.S. Cavalry had learned to fight Chiricahua Apaches.

Scouting across a portion of southeastern Arizona Territory from Camp Lowell, this detachment from Troop F, 3rd Cavalry was searching for Apache trails under the leadership of Lt. Howard B. Cushing.

“He was considered the most successful Indian fighter in the army; brave, energetic and tireless, he followed the foe to their strongholds and there attacked them with vigor and spirit, dealing them blows the savages could not withstand,” Thomas Edwin Farish reported of Cushing in History of Arizona.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Little did Cushing and his men know that they themselves were being stalked by their foe, who were more formidable than this storied Apache hunter had previously encountered.

Heading north from the Huachuca Mountains, the cavalry intended to stay over at the decommissioned Camp Wallen along the Babocomari River. The Apaches, however, had burned the grass, requiring, as intended, that the troops head 12 miles north to Bear Springs in the Whetstone Mountains, the next-nearest reliable water source. Just north of Camp Wallen, seemingly fortuitously, they encountered Apache footprints.

Mott’s small detachment recognized the pending ambush just as they entered a wash. This prematurely snapped trap was followed by an advance of eight men, including Cushing, who found his way into herodom, falling in battle with civilian packer William H. Simpson and Pvt. Martin Green.

Perhaps 165 Apache warriors were involved, as Mott reported, outnumbering the soldiers 15 to one. The warriors had been led by the legendary Juh, a Nednhi Apache living and operating mostly south of the U.S.-Mexico international boundary. Contemporaneous reports stated that this ambush was led by Cochise, but descriptions matched Juh’s stature. Juh’s son Asa Daklugie gave a later oral account, memorialized by Eve Ball, that supports this interpretation.

“In him,” History of Arizona noted of Cushing, “Arizona lost one of her most worthy defenders; a man who, at this critical time, she could ill afford to part with. He was the Custer of Arizona….”

— Photo courtesy Library of Congress —

Footprints into History

Despite the quintuple Medals of Honor site being exactly where Mott said the ambush site was, in a remote canyon in Cochise County, it has defied discovery…until now.

The quest to identify the isolated place where Lt. Cushing died began at the urging of Sgt. Jarrett Warmack, who sought to memorialize the Medals of Honor recipients in Fort Huachuca’s backyard.

Primary documents, including detailed accounts by survivors and the burial party, told us where, but the location had been obscured by time, reuse of the spot and invalid interpretations of seemingly clear narratives.

Cushing, Mott and other chroniclers reported misconceptions based on intentional deception by the Apaches. For example, the courageous woman who laid the tracks was likely not a woman at all, but a man leading a horse, so as to appear to be an unthreatening woman. Furthermore, while the cavalry was indeed heading toward Bear Springs, the soldiers never made it there, despite Capt. Alexander Moore and John G. Bourke identifying that as the location where the soldiers were taken while the burial party recovered the bodies.

Other erroneous postulations result from changes in the historical landscape over time. For example, two roads led north from Camp Wallen, not just one, as was generally assumed. This means that the Apaches likely laid their footprints in two locations, to intersect Cushing’s trail.

Subsequent changes in names of mountain ranges have also confused the picture, leading to incorrect interpretation of accounts. This is where archaeology and ethnographic understanding can be crucial in analyzing the historical record.

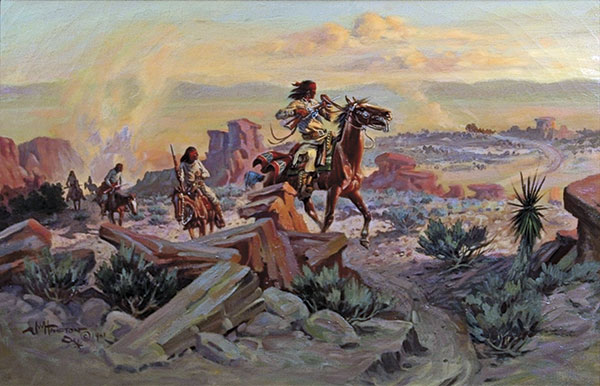

— Apaches Attacking the Prescott Stage oil by John Hampton Courtesy March in Montana, March 18-19, 2011 —

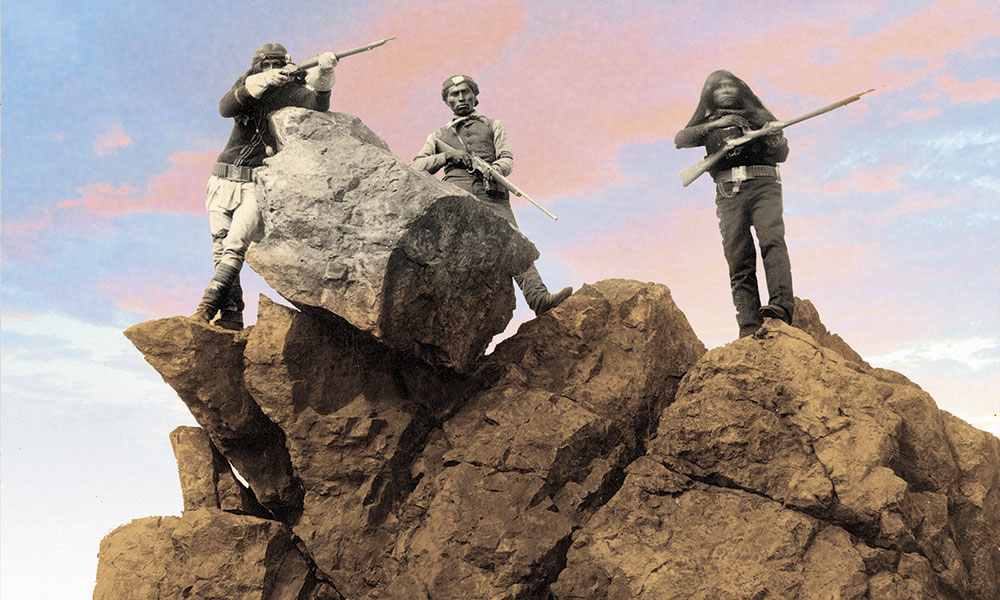

Ambush Behavior

I led an archeological team that found the hallowed location through hard-won understandings of Apache landscape use and ambush behavior. Only so many locations in this zone would have been suitable for an ambush by Apaches who viewed the area with a mid-19th-century perspective.

Cushing and Mott did not understand this aspect of regional warfare any more than modern-day historians did. This knowledge was gained through time. As the military encountered the enemy in similar fights, soldiers learned to read the terrain. They were schooled quickly after initial faulty assumptions based on their experience with markedly different Apaches.

Cushing felt an inflated sense of confidence owing to his previously successful engagements with the Pinals and other Apaches north of the Gila River and in New Mexico Territory. The military would learn that Apaches varied in their behavior between bands.

Assumptions about the way Apaches conducted war have also hindered modern understandings of the 1871 encounter. Popular literature characterizes the Apaches as disorganized fighters, each man out for himself, whereas they were quite organized and disciplined. Their proclivity to disperse when circumstances turned against them was part of a reasoned and successful strategy, not unpreparedness and cowardice.

Juh has been viewed as an exception to the rule that Apaches lacked leadership. Yet each key leader has been considered an exception, so the rule must be questioned.

Viewed in aggregate, many long-held perceptions are wrong about Apache battlefield behavior. The Chiricahuas learned the Sonoran-style guerilla warfare from an extended history of violent encounters; theirs was but a continuum of regional practice in irregular tactics that included hit-and-run strikes, ambushes and breaking up large formations, all of which stretched beyond the first observations recorded by European pen strokes. Honed over centuries, tactics usually attributed to Chiricahuas have deep roots among O’odhams and other regional tribes.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Juh’s Vengeance

Contrary to popular notions, the Chiricahuas planned their attacks and employed reasoned strategy. Unbeknownst to Cushing, renowned for his effectiveness and tenacity in campaigning against other Apaches, his route was orchestrated, seemingly choreographed, by Juh and his warriors. The Apaches had stalked the lieutenant from at least Pete Kitchen’s ranch along Potrero Creek near Nogales, Arizona Territory, leading the cavalry to the ambush site.

Those inclined to dispute this forethought will question why Juh would pursue Cushing. Juh’s son, Daklugie, said his father was enraged by Cushing’s attacks on New Mexico Territory encampments. Juh sought revenge as would any Apache obligated by tradition to seek retribution for such atrocities.

Finding the actual battlefield expands on Mott’s detailed account, informing us of the nature of warfare and the use of weapons.

— Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell —

Unlike battles by other Apaches at that time, the Chiricahuas did not use metal arrowheads; nor did the site reveal any stone arrowheads or lance heads. Just a year before, Apaches in the Pinal area were recorded using lances and bows and arrows.

The Nednhi band of Chiricahuas, headquartered in Mexico, instead used flintlocks and lead shot, while the cavalry defended with .50-70 Sharps carbines and Remington percussion cap pistols. This likely explains why so few shots were fired, as well as the closeness of the attack, allowing a warrior to snatch Pvt. Green’s hat from his head.

The Chiricahuas knew the terrain and deftly manipulated the movements of their enemy, maneuvering them into an ambush with the sole intent of executing Cushing.

Juh got his vengeance.

For 30 years, Deni Seymour, Ph.D has studied the ancestral Apaches, Sobaipuri O’odhams and lesser-known mobile groups (Janos, Jocomes, Mansos, Sumas and Jumanos). She is rewriting the history of the pre-Spanish and colonial period Southwest, and has authored six books and more than 100 articles.