– Courtesy Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records, History and Archives Division, #94-0011 –

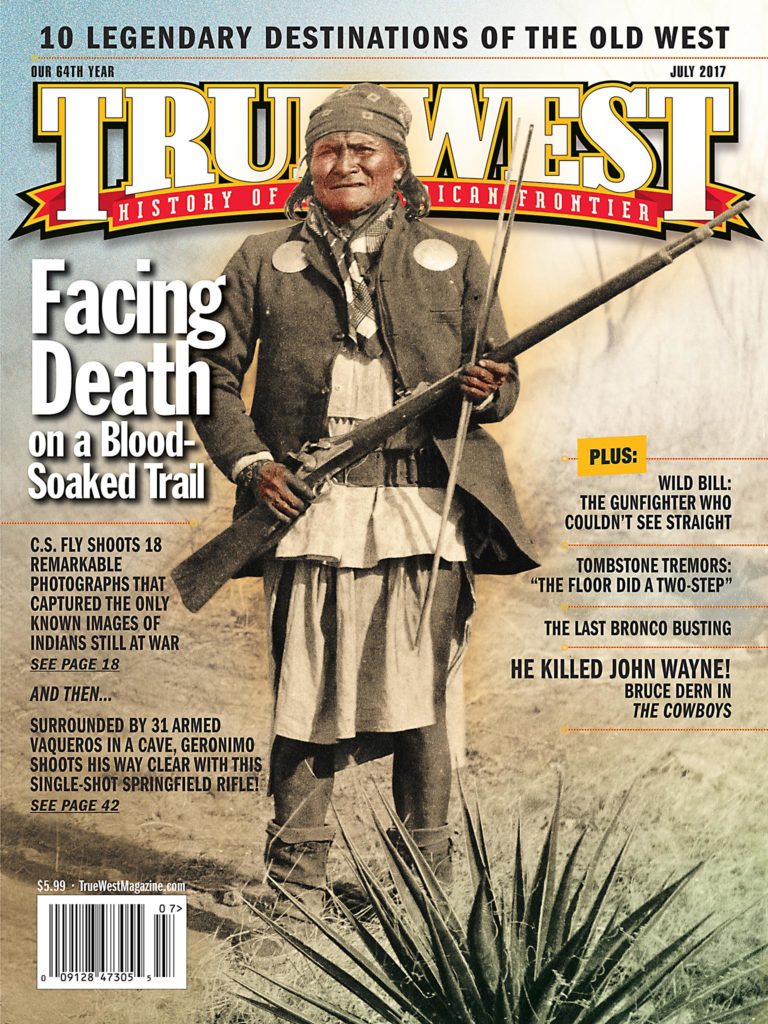

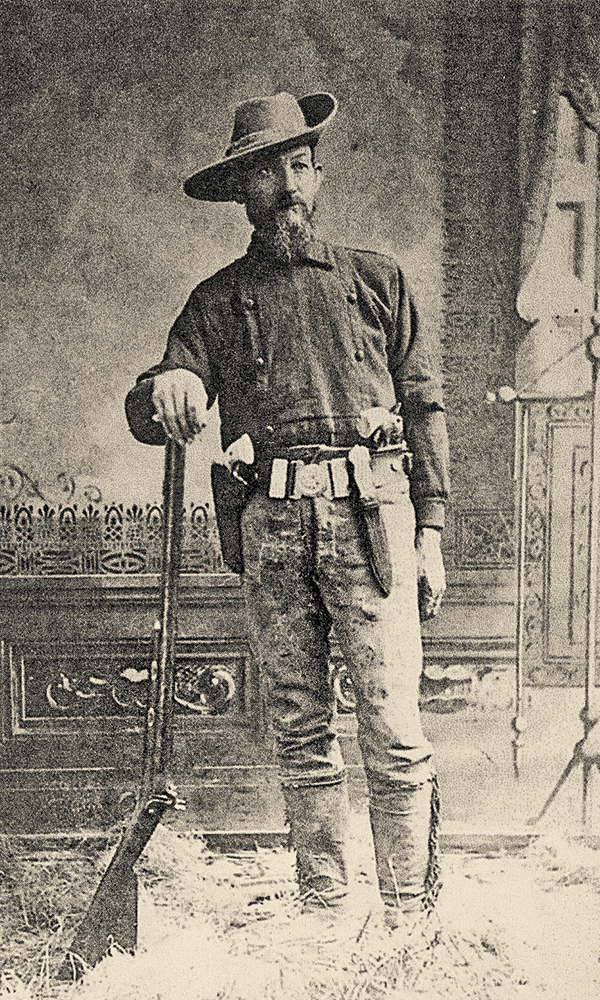

The rough and tumble days of Tombstone, life in nearby silver mines and that defiant stare of Geronimo’s all live on in black-and-white images thanks to the quick eye and daring nature of a tall photographer named Camillus S. Fly. Give a bigger hand to his wife, Mollie, for her foresight to preserve these moments, frozen in time in glass plates and negatives.

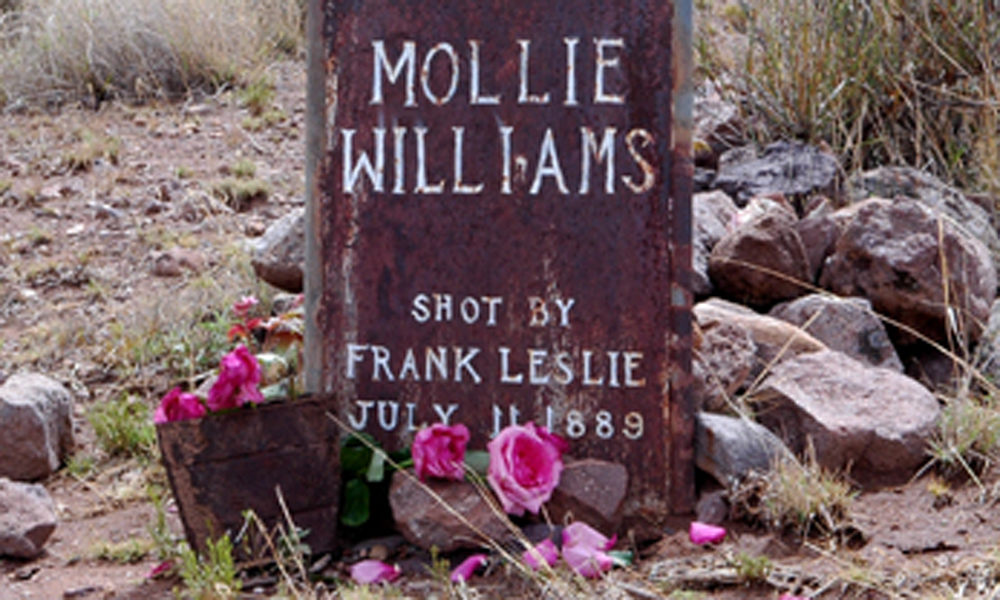

Born in Illinois in 1847, Mary Edith “Mollie” McKie was already a photographer when she met C.S. in San Francisco, California, in the late 1870s. Little is known about her early life, including why she divorced her first husband, Samuel D. Goodrich.

Historians disagree over whether she taught C.S. the photography business, but after the couple married on September 29, 1879, they moved to Arizona Territory that December and within months opened their studio in Tombstone. The mining town’s residents recalled how C.S., or “Buck,” did most of the field work for Fly’s Photographic Gallery, while Mollie took charge of the inside work, including studio portraits, the intricate color work and the business end.

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 11, 2016 –

Cora Henry, one of the couple’s two foster daughters, wrote in 1950 how her father worked: “You had a picture taken…[he] would bow you in and scrape you out.”

Cora was kinder about Mollie: “Mrs. Fly was a little woman of about five feet of pure dignity, very plainly dressed, but in manner[s,] Queen Victoria had nothing on her.”

Mollie was also enterprising, finding ways to make extra money. The couple ran a boarding house out of the studio, and, in January 1900, The Tombstone Epitaph reported the studio had opened a candy store. Several months earlier, The Tombstone Prospector reported on another business, directed at female customers.

“Ladies desiring latest styles in hats would do well to call on Mrs. C.S. Fly at the Photograph Gallery and examine the assortment of handsomely trimmed millinery offered at reasonable prices.”

What the papers don’t reveal were the long separations in the marriage due to Buck’s drinking and his mining and ranching attempts. Mollie was at his side, however, when he died in Bisbee, in 1901, from what the doctor called “acute alcohol toxicity.”

Despite several studio fires, Mollie saved what photos she could. She published a small book in 1905 that showed her husband’s greatest adventure, accompanying Gen. George Crook on his campaign to parley peace with Geronimo in 1886, during which C.S. had instructed the Apache warrior on how to pose for the camera!

In 1911, she sold the Fly negatives and plates to Arizona’s Territorial Historian Sharlot Hall.

Mollie then left Arizona forever, moving to Los Angeles, California, for her remaining years and dying in 1925. Her husband may have captured the Old West with his camera, but Mollie was the one who preserved it all for the rest of us.

Susan L. Sorg has roots stretching back several generations in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. She spent 20 years in TV journalism and has written articles published in True West, Arizona Highways, Cowboys and Indians, Western Art Collector and Native American Art. She lives with her husband, Ron, in Maine.