“Yes, I knew Charlie Russell—though not too well. I have always regretted that I did not know him better,” Maynard Dixon told an aspiring biographer who had asked about Russell in 1937, more than a decade after the cowboy artist’s death.

Dixon’s statement could easily be misunderstood if one did not know that the two artists were friends for nearly two decades. Yet like any of us feels about good friends who have come into our lives, they always leave us too soon for us to accept we have learned all we can from them.

Theirs was a friendship based on common interests of art and the American West, however different their perspectives might have been on the subjects. It was a friendship of mutual respect and recognition for the other’s view. Not too long after Dixon died in 1946, his second wife, the photographer Dorothea Lange, was asked to name her husband’s artistic influences. She replied, “He had a couple of old cowpuncher friends, whose opinions he valued very highly. One of them was Charlie Russell, a great American legendary painter.”

The East Brings the West Together

Russell and Dixon may not have been best friends, yet they enjoyed an infrequent kinship that began around 1908 and lasted until Russell’s death in 1926.

They found each other in the most unlikely of places, metropolitan New York City. In middle age at the time of their chance meeting, they recognized each other as kindred spirits; they later became the foremost artists of two different American Wests.

Long before the artists met, their Western experiences shaped their characters and likewise formed their insatiable love for the Old West.

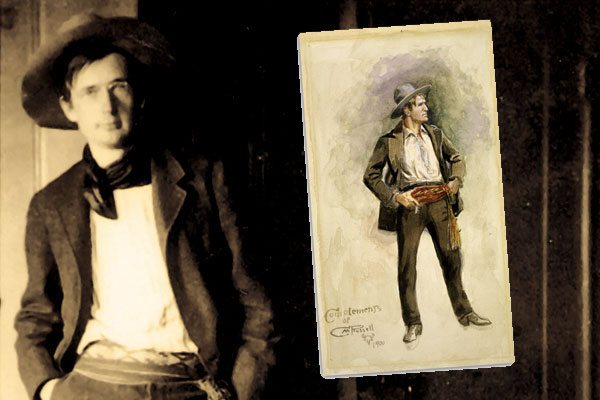

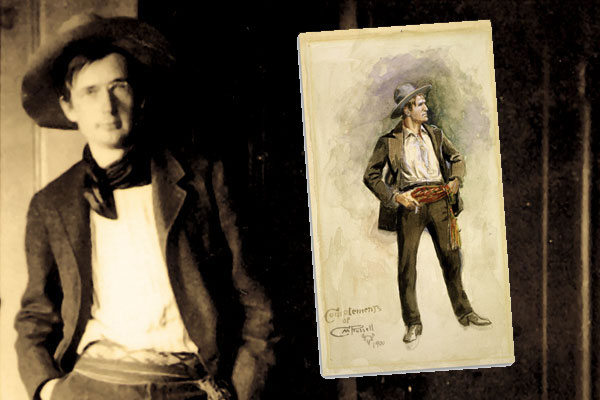

Russell, the elder of the two by 11 years, left his Missouri home for Montana at the age of 16. Shortly thereafter he became a night wrangler for the Judith Basin roundup. Progressing as an artist slowly but steadily in isolated Montana, Russell set his mind to serious oil painting in 1885. The artist continued to refine his craft throughout the 1890s, and by the turn of the 20th century was receiving some national attention. In his hometown of St. Louis, Missouri, he was described as the logical successor to Frederic Remington.

Dixon was born on the plains of the San Joaquin Valley in central California, near the boomtown of Fresno. The sickly youngster was in the midst of characters left over from California’s gold rush era. “Rocky Mountain trappers, miners and adventure seekers abound,” he later recalled of his youth. At 18, he enrolled at the California School of Design in San Francisco for formal art training but lasted only three months. The artist then turned to illustration for practical training and financial opportunity. Dixon published his first illustration in Overland Monthly at the age of 18. “The readers of the Overland Monthly are familiar with the work of Maynard Dixon, perhaps the coming rival of Frederic Remington,” touted Pierre Boeringer in the San Francisco periodical in July of 1895. By the turn of the 20th century Dixon, like Russell, had an enthusiastic following.

So how exactly did the two artists come across each other in New York City of all places?

On April 18, 1906, an earthquake devastated San Francisco and subsequent fires burned uncontrollably for three days. Many of the city’s artists lost their life’s work, and the tragic event forever changed San Francisco’s art community, which was then the art center of the American West. Most resident artists scattered. While many went to Europe, most painters and illustrators moved to New York City, the nation’s art and publishing capital.

Dixon did not jump on that bandwagon immediately, heading first to Los Angeles to seek out new opportunities. Yet, at 32, he did relocate to New York. His arrival in 1908 brought him good fortune; he landed commissions for Century magazine and became an instant success. In the subsequent years the artist would complete illustrations for Scribner’s, Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, McClure’s and Harper’s Weekly.

Dixon recalled first meeting Russell in New York in 1908 or 1909. At this point in their careers Dixon was likely the more famous of the two, at least on the coasts. “I first began to hear about Charlie Russell ‘the cowboy artist’ as far back as 1890,” Dixon recalled, “and from then on with fair regularity in almost any part of the west wherever pictures of western life might be mentioned.”

Russell had made frequent visits to New York since 1904 and was evolving as a painter at a feverish pace. In 1908, he completed several notable paintings, among them his iconic image of cowboys as hooligans, Smoke of a .45, and one of his greatest paintings, The Medicine Man. Russell was beginning to hit his stride, and these paintings were only an indication of what was to come. The artist’s use of color improved dramatically between 1900 and 1908, which can largely be attributed to his proximity to other painters. The Medicine Man and Smoke of a .45 far exceed anything Dixon had completed up to this point in complexity and ambition.

Matchmaker Edward Borein

Dixon and Russell shared a mutual artist friend, Edward Borein, and he was likely the occasion of their first meeting.

In 1893, Dixon and Borein had attended the California School of Design together. Eight years later Dixon accompanied Borein on a horseback trip through the Sierras.

Borein met Charles and Nancy Russell in the winter of 1908. Not only were Borein and Russell both cowboys of sorts, each was trying to find his way in the complex New York art world. Borein quickly sized up Russell’s work. “Me and Russell had each painted the same subject on canvas and after seeing Charlie’s painting, and comparing it to mine,” observed Borein, “I felt I had no business working in the same medium.”

In the following years Russell sent several commissions Borein’s way. Borein went on to enjoy a successful career as an etcher, and he completed some of his most famous works during the years he was close with Russell.

Borein’s “owl’s nest” at 138 W. 42nd Street was known as an informal meeting place for displaced Westerners. The bounty of Western characters who found their way to Borein’s studio made a lively scene for both Russell and Dixon to patronize. Actors including Leo Carrillo, Fred Stone and Will Rogers; fellow artists Jimmy Swinnerton, Will James and Olaf Seltzer; and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performers including Annie Oakley were all visitors to Borein’s makeshift Western studio.

Dixon’s studio likewise became a hub for camaraderie; additional patrons included Western writers Eugene Manlove Rhodes, Emerson Hough and Andy Adams, and artists including Ernest Blumenschein and Robert Henri.

Russell made several trips between Montana and New York during the years 1910-12. He was continuing his ascendancy into the national consciousness, through lucrative commissions with the calendar company Brown & Bigelow and the Ridgley Printing Company, and by securing a major mural commission in the Montana state capitol. In 1911, Russell’s exhibition, “The West that Has Passed,” at Folsom Galleries in New York (on Fifth Avenue, across the street from Tiffany & Co.), was a milestone in the artist’s career. One would assume that Dixon saw the exhibition of 13 oils, a dozen watercolors and six bronzes. Russell would follow with exhibitions at Folsom Galleries in 1912 and 1913.

Yet 1912 was the year Dixon left New York and returned to San Francisco, where he re-established himself.

Friendship from Afar

Back in California, Dixon did not forget his new compadre. He wrote Russell requesting his company on a painting trip to the September 1913 rodeo in Pendleton, Oregon. Russell graciously declined, as he had just returned from the Winnipeg Stampede. He kindly reciprocated by inviting Dixon to visit him at Lake McDonald or Great Falls.

Although Dixon’s letter to Russell no longer exists, Russell’s response to it indicates Dixon included photographs of the murals he was creating for Anita Baldwin in 1912. The mural commission was a landmark in Dixon’s career; he’d later write: “As a painter, then, I date 1912.”

Newspapers in Los Angeles and San Francisco praised the murals for their beauty and scope of design. Russell, too, responded with praise: “Think your pictures were fine they looked mighty real to me your Indians ponees and ldges [lodges] were all mighty shookum I am glad of your success and hope you keep pulling of[f] good things till your light goes out and hope it burnes long and bright with out a flicker.”

Although Russell was complimentary in his response to Dixon’s paintings, his comments were likely not what the California artist was searching for. Dixon would have been more concerned with the painterly qualities, execution of design or overall aesthetics of the works, but Russell commented on what he considered important—“they looked mighty real.”

Russell’s comments are a testament to the differing approach of the two artists. In 1937, Dixon reflected on Russell’s approach: “Natural fact and historical accuracy were his aims; imagination, interpretation—a re-creation of the subject matter—to him were nonsense.”

In contrast, Dixon was quoted in The Los Angeles Times as stating that the “melodramatic Wild West is not for me the big possibility. The nobler and more lasting qualities are in the quiet and most broadly human aspects of Western life.

I aim to interpret, for the most part, the poetry and pathos of the life of Western people, seen amid the grandeur, sternness and loneliness of their country.”

Dixon aligned himself with the arid Southwest, while Russell is associated with Montana and subjects of the northern Plains. One needs to look no further than the artists’ monograms, which they include in their signatures, to see that each artist wanted to identify himself with a region. Russell’s famed buffalo skull, which he copyrighted in 1906, came to signify the passing of the Old West through the near extinction of the buffalo herds of the northern Plains. Dixon chose a thunderbird as his mark of distinction; a mythic figure of Southwest Indian lore, the thunderbird possesses the power to generate storms.

Dixon Visits Russell Country

The artists’ first visit since their time together in New York took place almost a decade later.

In 1917, representatives from the Great Northern Railway approached Dixon about producing paintings of Blackfeet Indians for use in promotional materials for the railroad’s lodges in Glacier National Park. Within a few weeks Dixon wrote Russell proposing that he and the Chicago artist Frank B. Hoffman would drop by Lake McDonald for a visit while on assignment in Montana.

“Will be glad to see you over here,” Russell replied quickly, “and when you come the robe will be spred [sic] and the pipe lit.” He continued, “There are no injuns here but there is lots of good picture country and I think we can have a good time.”

At that time, Dixon was recovering from an emotional and physical breakdown from the prior year, brought on by his irreconcilable marital issues and financial problems. He had recently divorced his first wife Lillian Tobey, and the journey to Montana was a welcome one. The artist wrote to his mentor Charles Lummis from Red Eagle Lake, Montana: “The world, and all that’s in it, is too far away to care about.”

After arriving in Glacier National Park in August of 1917 and touring the park, Dixon made his way to Bull Head Lodge to reunite with Russell. Bull Head Lodge was surrounded by dark woods that limited the views of the sky, making it almost impossible for Dixon to paint as he was accustomed and thus possibly limiting his stay. Dixon had a self admitted “weakness” for horizontal lines and preferred distant horizons.

“I did not think too much of the mountains,” he wrote to Western author Dane Coolidge, “but the Blackfeet are the best Indians I have seen yet, bar none.”

Dixon and Russell enjoyed each other’s company while at Bull Head Lodge and likely spun yarns or traded anecdotes on Western lore, which both artists were known to do well. Seven years elapsed before they would see each other again, and the next time Russell would be on Dixon’s turf.

Russell’s California Dreams

In 1920 Charlie and Nancy Russell began their winter sojourns, escaping the harsh Montana winter to find new prospects for art sales in southern California. During Russell’s visits, Borein introduced him to local artists such as Carl Oscar Borg, Frank Tenney Johnson and Thomas Moran. Russell again found himself among a circle of Western types as he had in New York.

All the while Nancy was making quick sales of Charlie’s paintings. In March of 1923 The Los Angeles Times reported the sale of six paintings totaling $20,000, to which Lummis famously responded, “You’ve shown ’em an American artist can get European—or Dead Men’s—prices.”

Meanwhile, Dixon had married photographer Dorothea Lange in March 1920, and he was frequently absent from San Francisco. His own travels may account for his failure to connect with Russell between 1920 and 1924.

His absence from the city may not have been the only reason the two failed to connect, since, according to Russell’s sole protégé Joe De Yong, “Mrs. Russell doesn’t like him [Dixon] but he is sure a go getter at some angels [angles] of the paint game.”

Nancy tended to not like any other painters, especially one of Dixon’s caliber, whom she would have seen as competition for potential sales.

Although the artists had little connection during this period, Russell wasn’t totally out of Dixon’s mind. On New Year’s Day 1920 Dixon sent Russell a poem titled “To an Old Timer,” using “old timer” as a term of endearment for Russell.

Great Talk Fests

Beginning in 1924, Russell and Dixon saw each other more frequently. They both exhibited at Los Angeles’s Biltmore Salon, and Russell visited Dixon in San Francisco whenever he traveled south to Los Angeles in the fall.

“He knew that Dixon and Ed Borein would come down to the train, and we would meet him,” illustrator Harold von Schmidt wrote about Russell. “Then they’d have a great talk fest, spend all day and all night talking, go from one restaurant, then on to another ending up in a coffee joint that was open all night. Then we’d go back to Dixon’s studio and talk some more. He’d finally take the morning train, the Lark, to Los Angeles.”

Lange recalled another visit Russell made to Dixon’s studio when she took a photograph of Russell: “What I remember is the atmosphere, the light, the qualities of easy going conversation or communication between Charlie Russell and Maynard Dixon…. However I do know that this was a serious conversation. They were not on this occasion spinning yarns, or trading anecdotes on western lore, or entertaining each other, which both these men knew how to do very well. I seem to remember that Charlie Russell was just passing through town. I never saw him again, or heard of his being in San Francisco again.”

Russell died in October 1926. Dixon would survive his friend by 20 years, and many of his greatest works were still ahead of him at the time of Russell’s death.

Their visions of the American West certainly differed. Yet their friendship likely enriched each other’s art for the better. If only we could have known more about their friendship.

Thomas Brent Smith is director of the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum. As a former curator at the Tucson Museum of Art, he organized the exhibition “A Place of Refuge: Maynard Dixon’s Arizona” and authored the eponymous companion publication. This edited excerpt appears in its full-length version in Charlie Russell & Friends, published by the Denver Art Museum and distributed by University of Oklahoma Press.