— Bannock photo by Mark Holloway —

Looting, wildfires, pollution, vandalism, time, the elements—Western ghost towns have lots of enemies. Thankfully, they’ve also got friends like Krista Evans.

“I love abandoned landscapes. They’re very beautiful and a little surreal,” Evans says. “I like imagining how they might have been in their heyday, when they were a happening place, but I also love the quiet of them now.”

Evans loves frontier ghost towns so much, she devoted her master’s thesis to their preservation, focusing on four sites that were founded during the late 1800s and abandoned by the mid-1900s as hard rock mining towns in Montana and Idaho.

When she was growing up in northern Michigan, Evans found “lots” of old mining sites to explore. So when she looked west, she saw the importance of these remaining ghost towns to both history and tourism.

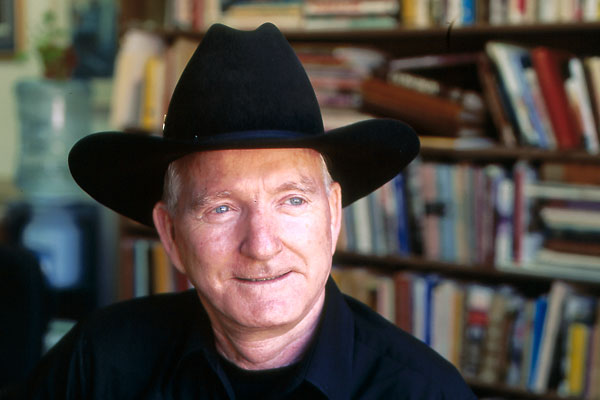

— Evans photo courtesy Krista Evans —

While interviewing ghost town visitors, for her thesis at Central Washington University in Ellensburg, she learned they wanted to see places they deemed “authentic”—where they could experience the real past. Sometimes that meant “wandering desolate streets that are flanked by dilapidated buildings of weathered wood, verging on collapse,” Evans says. Or walking into a building that still has an uneaten dinner on the table, as if its residents just walked out the door. Or attending a festival like those enjoyed by the townsfolk when they lived there.

But how do you provide that authentic experience without jeopardizing safety? How do you keep deteriorating buildings looking that way without them falling apart under the normal strains of age?

Some ghost towns in the West have adopted an “arrested decay” strategy, Evans found—they stabilize the buildings, but keep the roof sagging and soak new nails in cola soda to make them appear old and rusted.

Others have opted to restore buildings—to present the ghost town in its “historic boom,” including interpretive events and re-creations. Still others let the buildings decay until they collapse.

In her research, Evans was particularly taken with Bannack, Montana, a “hybrid” that presents both a desolate frontier town and an occasional glimpse into the Western myth. Bannack has more than 60 well-preserved buildings that front a main street “so quiet and forlorn, that it is not uncommon to see a deer or tumbleweed slowly ambling by,” Evans says.

But annually, the ghost town hosts “Bannack Days” that draws thousands of visitors to experience history skits, storytelling, music, vendors and re-enactors in period clothing.

“Ghost towns provide visitors with an unsurpassed opportunity to step back in time and encounter the shadows of those who settled the Western frontier,” Evans wrote in a paper about her research.

She could have been talking of her own fascination, for she admits that ghost towns have captured her “imagination and heart”—letting her hold hands with the bygone frontier.

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.