“A genuine mountaineer is a…kind of sui genus, an oddity, both in dress, language and appearance, from the rest of mankind.”

“Associated with nature in her most simple forms by habit and manner of life, he gradually learns to despise the restraints of civilization, and assimilates himself to the rude and unpolished character of the scenes with which he is most conversant….His head is surmounted by a low crowned wool-hat, or a rude substitution of his own manufacture. His clothes are of buckskin, gaily fringed at the seams with strings of the same material, cut and made in a fashion peculiar to himself and associates….”—Rufus B. Sage, in 1857’s Rocky Mountain Life: or, Startling Scenes and Perilous Adventures in the Far West During an Expedition of Three Years

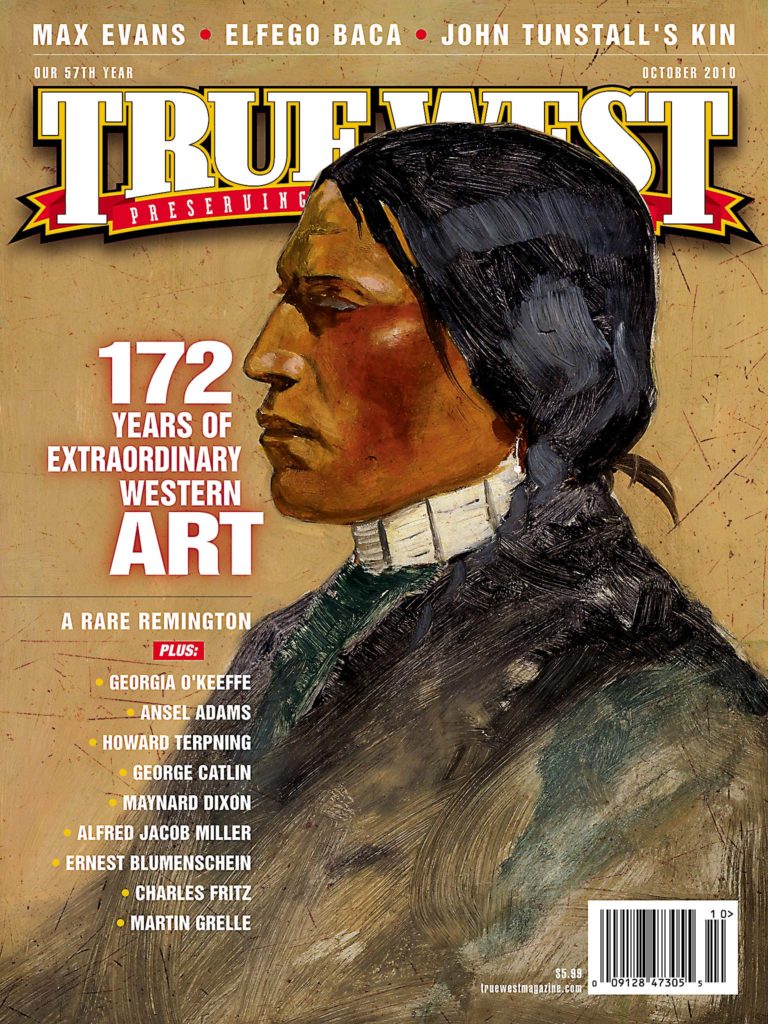

The fur trappers, traders and Mountain Men who traversed the prairies and the mountains between the Great Lakes and the Mexican territories to the south and west learned quickly to live off the land.

Seasonal changes in the West brought extremes in temperature and inclement weather that required protective clothing. As described by Rufus Sage in his account of his 1841-44 expedition through the region, most of these early pioneers relied on animal hides and furs for their clothing, just as the Indians in the region did. Yet even the wildest of these trailblazers wore garments that were somewhat tailored. Where the Indians wore ragged edged hides and skins, the white men among them managed to create sleeves.

As trade with the Indians flourished, blankets and textiles replaced hides and skins as the preferred materials for clothing. Indians warded off cold winds and rain by wrapping themselves in brightly colored wool blankets. Like their French voyageur counterparts in the Great Lakes region, white trappers created hooded coats out of the blankets, which they called capotes.

The cowboys who moved herds of Texas cattle to the railheads in Kansas, and the settlers who ultimately plowed and fenced the prairies wore more traditional European-style coats and jackets made from woven wool, linen, hemp and cotton. Canvas dusters and oil- and wax-impregnated slickers warded off wind and rain in warmer seasons; wool coats and jackets, including Mackinaws and capotes, were common in winter. Women often wore cloth cloaks, capes and shawls to protect them from the elements.

Leather was worn by buffalo hunters and Army scouts who were more closely associated with the Indians—and thereby damned by that association among folks who still feared the original inhabitants.

Many of those early, highly functional styles are still part of the Western wardrobe. Indian-inspired designs are popular standards. Capotes come and go with styling trends and availability. Capes and ponchos, their Hispanic cousins, are making a fashion comeback.

Outerwear is the one Western category that has shown the greatest acceptance of synthetic materials, such as poly fleece and Thinsulate insulation. Outerwear is also unique in that it embraced a foreign interloper in the late 20th century—the Australian drover coat. With its rainproof exterior, signature caped silhouette and Australian stockman’s pedigree, oiled-and-waxed coats and jackets are as much a fixture in the wardrobes of contemporary Westerners as a sheepskin ranch coat or an Indian-patterned cape.

Yet make no mistake, just as in the case of Sage and his peers, the outerwear donned by a Westerner today is still very much “made in a fashion peculiar to himself and associates.”