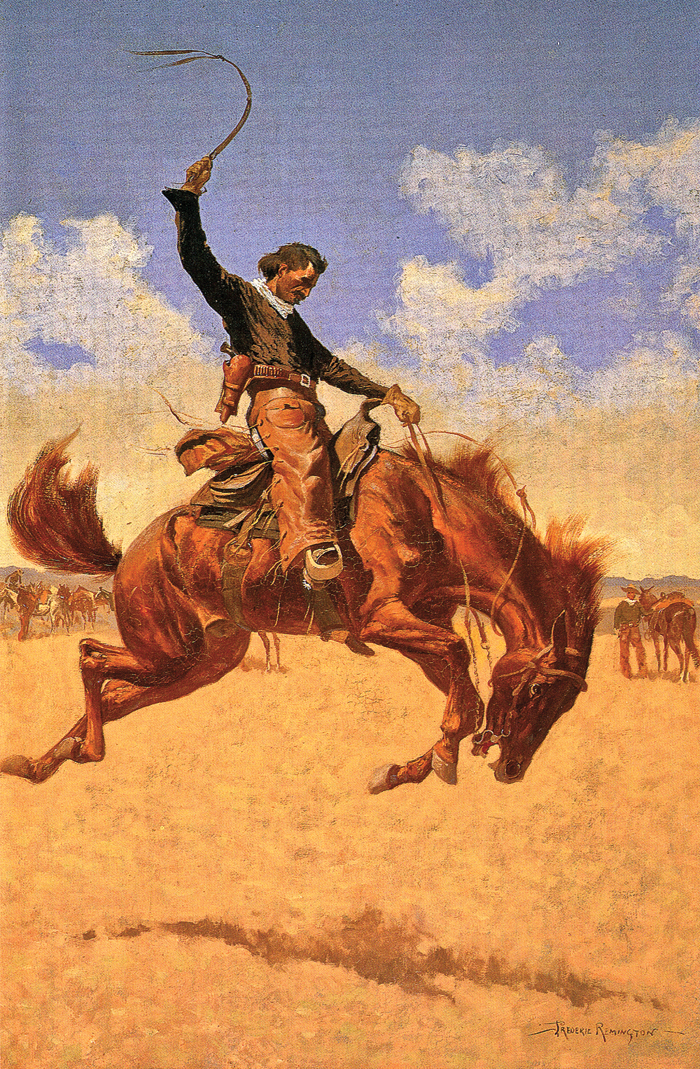

Fifteen years younger than Frederic Remington, Frank Tenney Johnson painted well into the 20th century, establishing himself as one of the finest artists of the early frontier school with his masterpiece, the 1935 36 x 48-inch oil Rough Riding Rancheros.

– Courtesy National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City; 1969.191 –

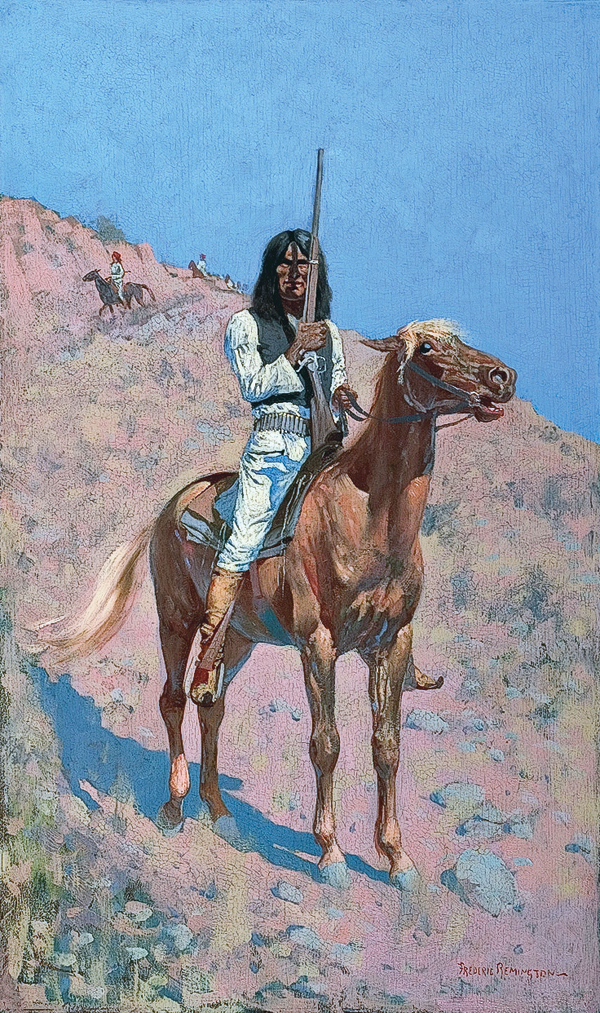

“The soldier, the cowboy and the rancher, the Indian, the horses and the cattle of the plains will live in his pictures and bronzes, I verily believe, for all time.”

President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1907 analysis of artist Frederic Remington’s legacy has been proven right. Remington (1861-1909) not only lives on in his art, but he continues to inspire other artists, just as he did during his lifetime when Charles Russell, Charles Schreyvogel and Frank Tenney Johnson followed the “School of Remington.”

An Easterner, Remington immortalized the West as a painter, illustrator and sculptor during The Golden Age of Illustration.

That period, loosely from 1850-1925, “was a time of great innovation and progress in the United States, and the country’s nationalistic pride and self-confidence spread to the arts,” Melissa W. Speidel writes in Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné II (University of Oklahoma Press, $75), edited by Peter H. Hassrick.

“Part of Remington’s fame very likely had to do with the fact that, as an illustrator for the leading magazines and periodicals, his work entered so many households at a time when mass media was just becoming a phenomenon,” says Maggie Adler, assistant curator at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Forth Worth, Texas. “People could see his art and read his stories all across the country. Also, as someone who was working for the popular press, he developed a keen sense of how to communicate clearly and readily.”

So it was only natural that artists followed Remington’s resumé.

While Howard Pyle focused on pirates, others—like Taos, New Mexico, artists W. Herbert “Buck” Dunton and Edward Borein—found their way west. N.C. Wyeth, on the other hand, excelled at pirates and cowboys.

Later, Remington’s influence could be found in the Golden Age of Western Pulp (1920-1960), which Deborah Bernhardt, collections chair at Trinidad, Colorado’s A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art, suggests provided the “model for the clean-cut Hollywood cowboy in the movies to come.”

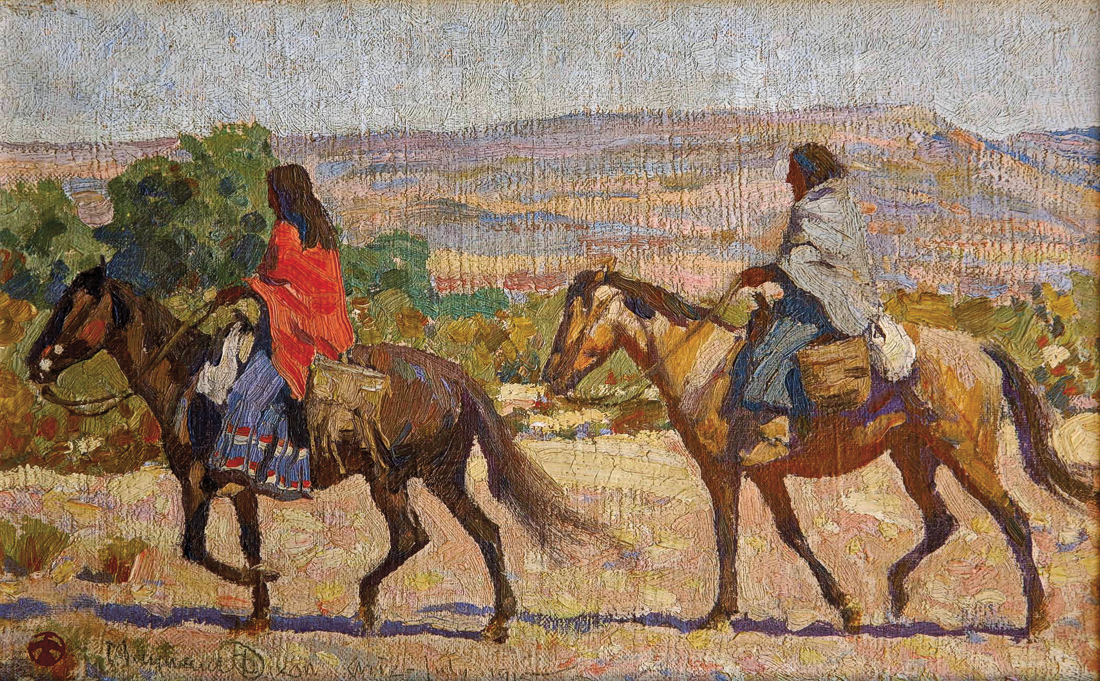

Artists from the Golden Age of Illustration influenced the artists of the Golden Age of Western Pulp including Maynard Dixon (who at age 16 got a letter of encouragement from Remington), Thomas Hart Benton, John Stuart Curry, Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth and A.R. Mitchell himself.

“Deadline demands probably made [Mitchell] up his game,” says Paul Milosevich, who studied under Mitchell. “Come up with a strong, eye-catching design that would jump off the magazine racks. Bright complementary color contrasts, bold silhouette shapes that could be read and understood at a glance, like a billboard.”

Yet not all artists were driven by the commercial art market.

“Tom [Lea] didn’t pay attention to the art market because he didn’t function in the art world,” says Adair W. Margo, founder and president of the Tom Lea Institute in El Paso, Texas. “He participated in the whole world, being motivated by ideas and historic events around him. The idea of ‘reinventing’ himself would never occur to him. He was fully and confidently himself.”

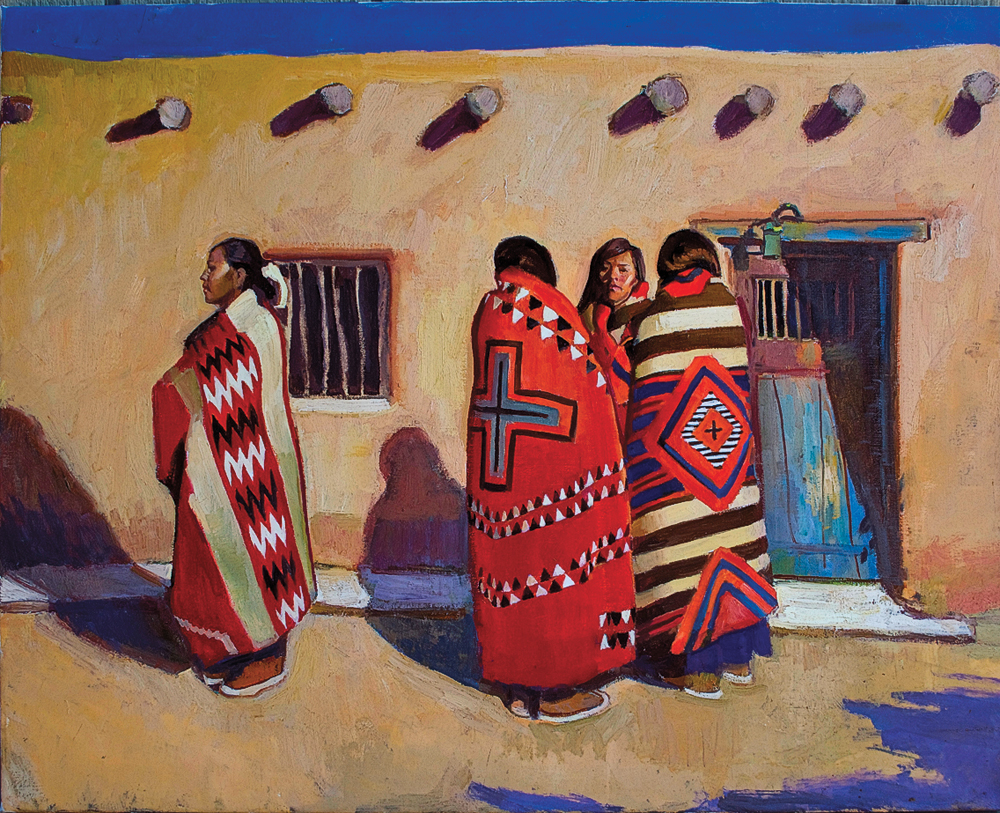

They painted cowboys, but also—especially the Taos artists—painted Indians.

“Most good artists have always been sensitive to the subtleties of the conflict between American Indians and the tidal onslaught of European Americans,” says Andy Thomas, a historical painter in Carthage, Missouri. “There were, however, gross caricatures in movies, popular fiction and some illustrative works that made Native Americans look comical. When I paint anything involving Indians, I always try to read all I can about the person I am painting and paint him or her as a person.”

During a 2015 residency in Omaha, Nebraska, Brad Kahlhamer found inspiration

in the Joslyn Art Museum’s collection of 19th-century ledger drawings and Karl Bodmer

prints and watercolors to create what chief curator Toby Jurovics calls “a quasi-mythological realm where lived and imagined experiences co-exist.”

Even an artist like Santa Fe’s Billy Schenck, whose influence is more Andy Warhol and Sergio Leone, pays tribute to artists like Frederic Remington. “My work is so completely, heavily referential to all the Western people, all those other artists who came before,” Schenck says. “It’s not just your superficial traditional Western painting made for the market. I’m trying to be an effete historical snob.”

Has cowboy and Indian art really changed all that much since Remington’s day?

“In a lot of ways it hasn’t, and that’s its strength,” Bend, Oregon, artist Michael Cassidy says. “The values don’t change. They’re eternal. They’re not subject to the changing whims of men.”

Besides, there’s one constant for artists that was true in Remington’s day and remains true today.

“You paint for the love of it,” Cassidy says, “or not at all.”

Johnny D. Boggs’s favorite Western artist is N.C. Wyeth—at least for today.