Robert M. Utley

October 31, 1929 – June 7, 2022

A former student’s personal tribute remembers a great historian, mentor and friend.

Robert M. Utley—the Old Bison, as he styled himself—passed away on June 7, 2022, in Scottsdale, Arizona, where he had lived the past 13 years with his wife of 42 years, Melody Webb. He was my dear friend, professional mentor and surrogate father. He was also our greatest Western historian of the last half century.

Born in Bauxite, Arkansas, on October 31, 1929, Utley was mostly raised in Indiana, where he attended the rival Hoosier schools Purdue University (BA, 1951) and Indiana University (MA, 1952). His master’s thesis, “The Custer Controversy,” written under the direction of Oscar Osburn Winther, reflected his fascination with George Custer and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. It had been a viewing of Errol Flynn as Custer in the 1941 film They Died With their Boots On that had set the 12-year-old boy on this lifelong obsession. This led him to seek a position as an “historical aide” under crusty old Major Edward Luce at Custer Battlefield National Monument in Montana. He spent six summers there, during which time he interviewed Charles Windolph, the last 7th Cavalry survivor of Custer’s last battle (in which he had earned the Medal of Honor). This gave Utley a personal connection to the battle that he always cherished.

His academic career was interrupted by a stint in the Army, where he eventually served as a historian in the Pentagon. He married not long after leaving military service, and the birth of two sons—Donald and Philip—ended any thoughts of returning to Indiana to study for a doctorate in history. In 1957 he accepted a position with the National Park Service as regional historian in the Santa Fe office. Thus began a long career with the NPS that soon took him back to Washington as chief historian for the agency from 1964 until 1972, as assistant director for historic preservation until 1977 and as deputy director of the President’s Advisory Council on Historic Preservation until his retirement in 1980 to pursue writing full time. In this work Utley essentially wrote the guidelines and standards for historic preservation still in use today. He was a man of considerable certitude and could be rigid in his enforcement of preservation rules, but even those who tangled with him never questioned his bedrock integrity. Little wonder that in 2007 True West published a cover story on him titled “The Man Who Saved the West.”

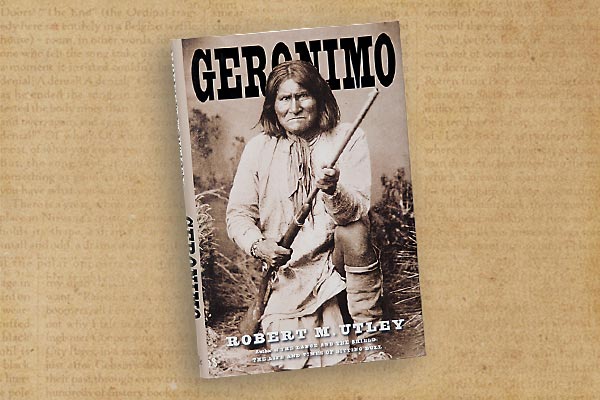

Utley began his writing career in 1949 with a self-published 52-page pamphlet titled “Custer’s Last Stand,” which was sold in a little gift shop (at 75 cents a copy and it quickly sold out) just down the hill from the battlefield. Today it is quite the collector’s item, although it later proved something of an embarrassment to its distinguished author. He was much prouder of his next publication, Custer and the Great Controversy (his revised master’s thesis) in 1962, which he followed up with his highly regarded Last Days of the Sioux Nation in 1963. In the years to follow he would publish 23 acclaimed books on a wide variety of Western topics—from the military frontier to the mountain men and from celebrated outlaws to the Texas Rangers. Utley proved particularly adept at biography, writing prize-winning books on Custer, Billy the Kid, Sitting Bull and Geronimo. He received many awards for his writing, including the Caughey Prize from the Western History Association, four Spur Awards from Western Writers of America (as well as the WWA Wister Award for lifetime achievement in 1994 and induction into the WWA Hall of Fame in 2015), and four Western Heritage Wrangler Awards from the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

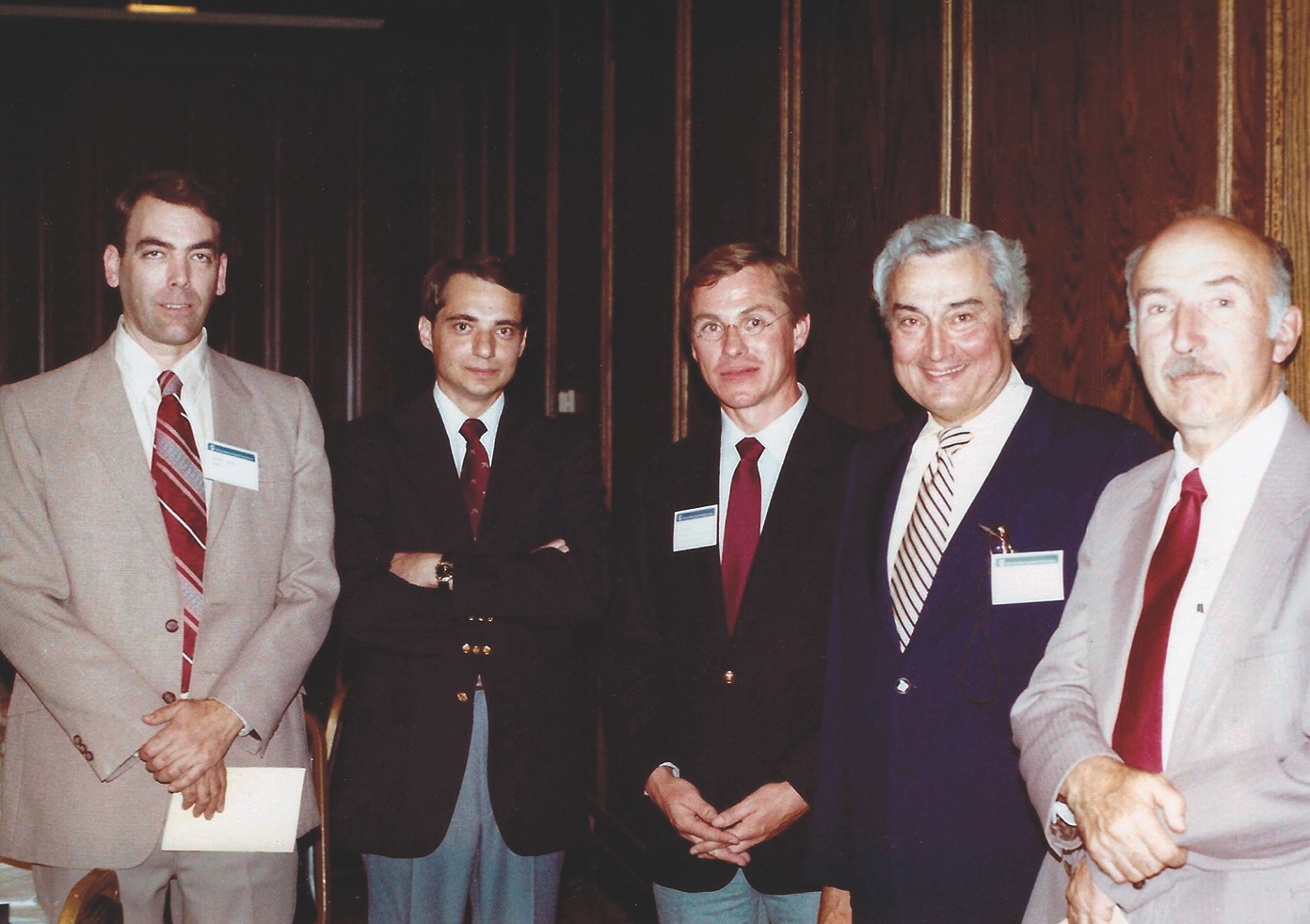

As one of the founders of the Western History Association in 1961, Utley kept his feet firmly planted in the worlds of both academic and popular history. Although he enjoyed the respect and friendship of many academics, he nevertheless wrote not for the professor crowd but for the greater interested public (the audience of this magazine). His goal was to convey through his writing his own passion for our rich Western heritage—and he certainly achieved that goal. He has long been regarded as the “Dean of Western Historians,” and his passing marks the end of an era in the writing of Western history. We shall not see his like again.