– Courtesy Anthony Powell Collection –

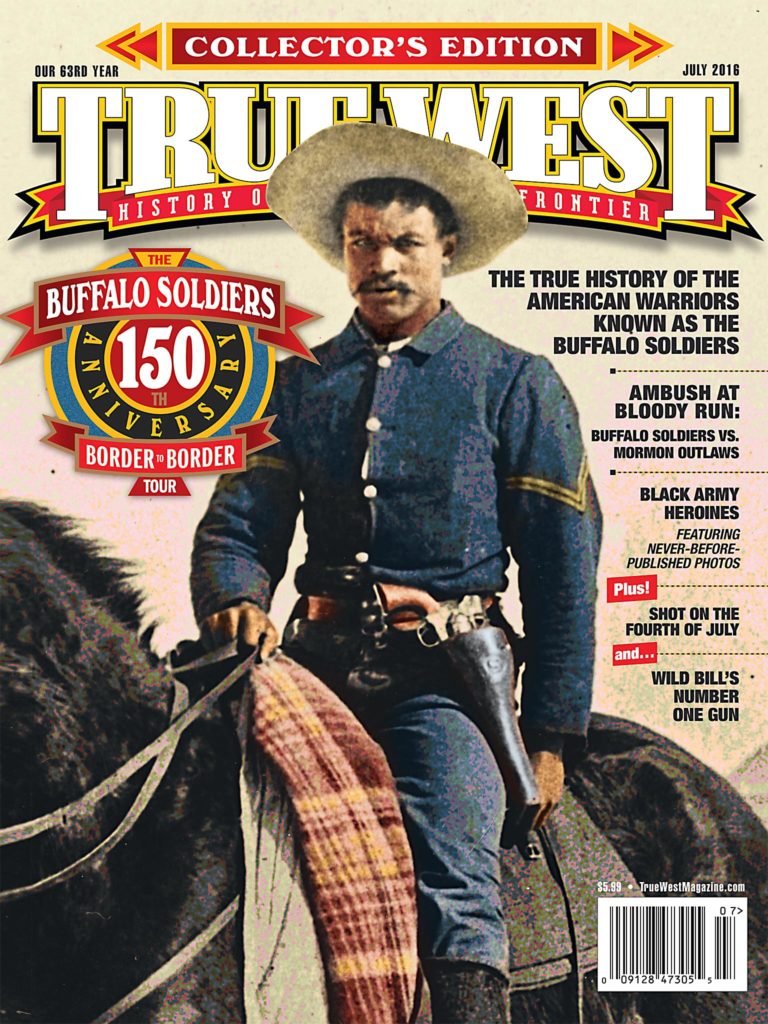

One hundred and 50 years ago, radical Republicans led the charge to create opportunities for blacks when, for the first time, they opened the ranks of the regular U.S. Army, which, prior to 1866, had been the exclusive domain of whites.

Acting on a variety of motives, ranging from rewarding Civil War officers and the black troops they commanded who had bought freedom with their blood to providing employment for large numbers of formerly enslaved blacks, legislators drafted a bill to add six segregated black units to the Army. This law brought about the creation of the 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalry Regiments, along with the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st U.S. Infantry Regiments. Three years later, another reorganization of the national martial establishment consolidated the original four outfits of doughboys into two units, the 24th and 25th U.S. Infantry Regiments respectively.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

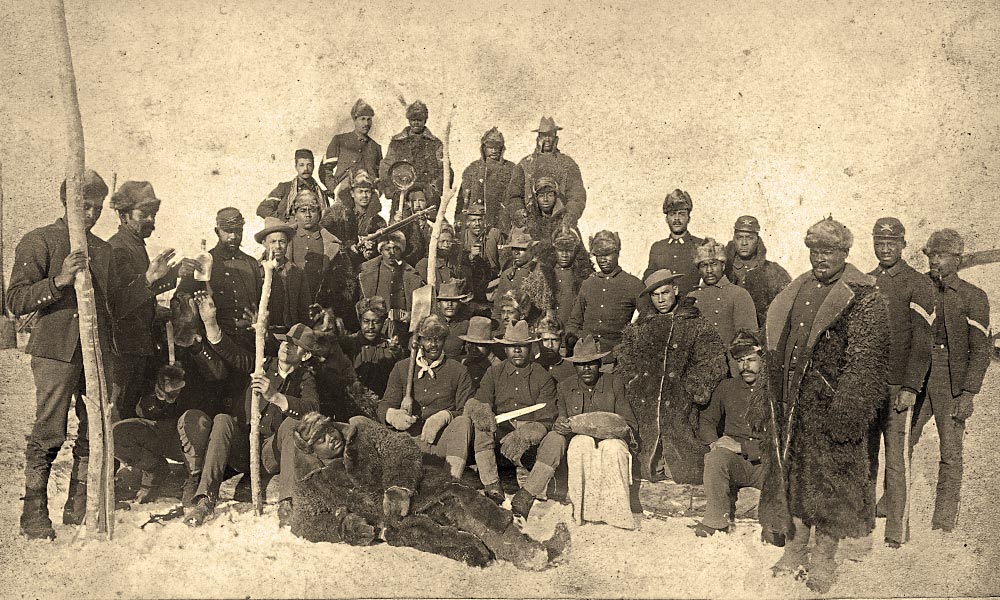

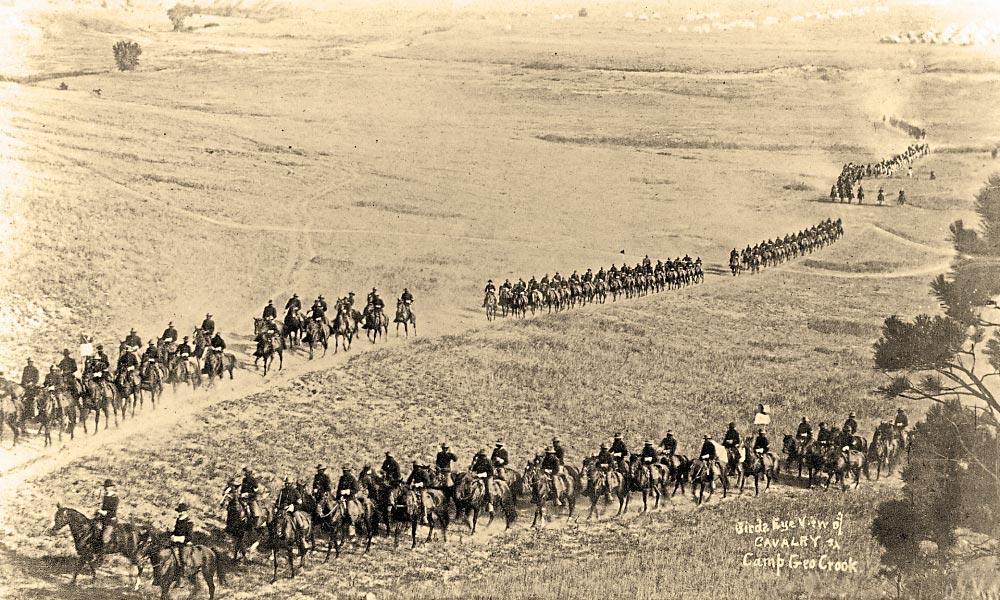

For the remainder of the 19th century, these black cavalry and infantry regiments constituted nearly 10 percent of Uncle Sam’s fighting force in the West. Over this period, these troops typically carried out their duties on the frontier, away from the centers of white population, supposedly because of political pressures to “keep blacks from being stationed in northern states to avoid possible racial conflicts.” The country abolished slavery and provided for the vote, but true equality was another matter.

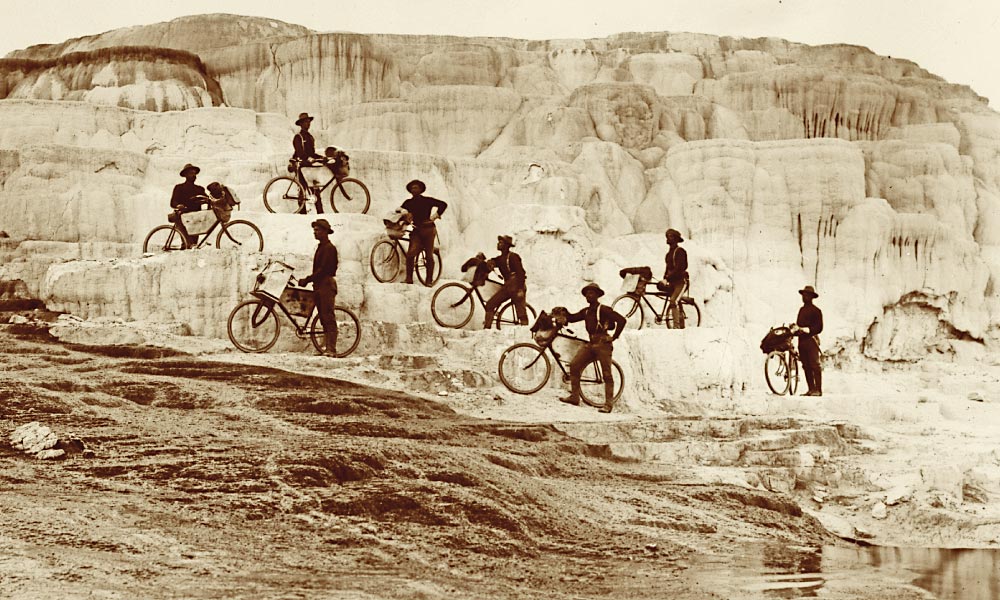

Despite discrimination, blacks in Army blue performed the full array of missions that fell to all frontier soldiers. Living solitary lives at remote posts far from their homes east of the Mississippi River, they endured the monotony of garrison life. The routine of work details and drills, and Spartan meals occasionally gave way to service in the field. They guarded railroad construction, escorted stagecoaches and military paymasters, protected the “talking wire” telegraph lines, patrolled the troubled and sometimes violent border between Mexico and the United States, built roads and served as peacemakers in places like Sheridan, Wyoming, during the contentious Johnson County War. Some even took part in an innovative experiment that would test the practicality of the bicycle for military purposes in mountainous country, riding more than 1,900 miles from Fort Missoula in the far west of Montana to St. Louis, Missouri.

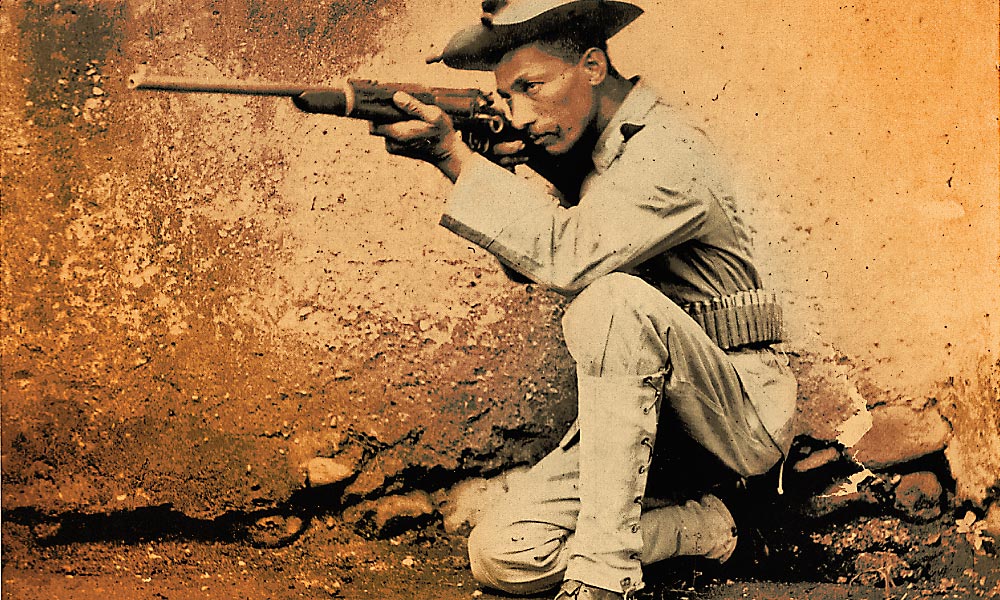

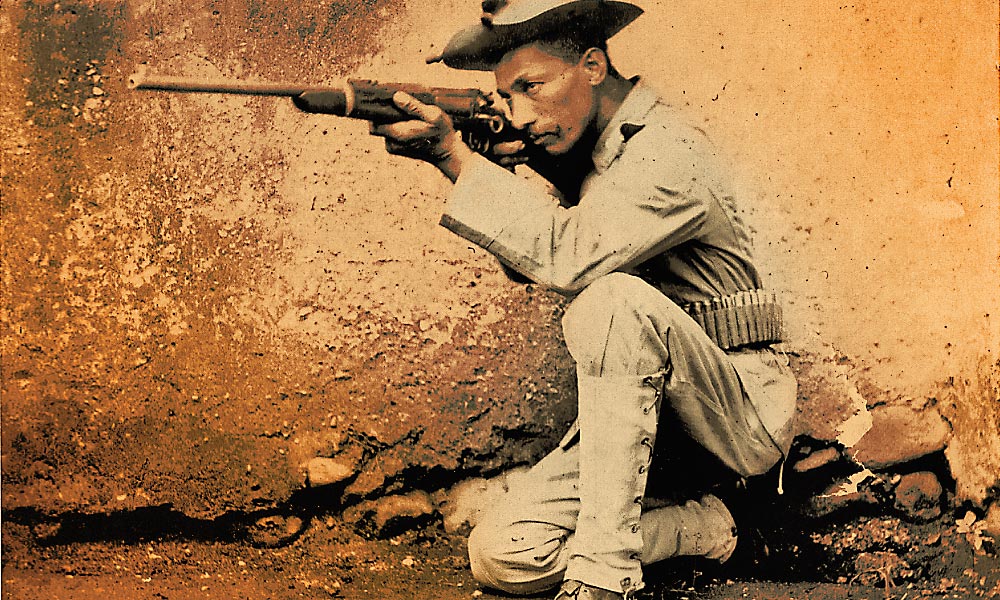

On many occasions, black soldiers clashed with outlaws and Mexican revolutionaries, and campaigned against determined, skillful American Indians in a new, daunting landscape. Black troops were involved in hundreds of skirmishes, from Beecher’s Island to Wounded Knee. They even ventured into Mexico as part of Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing’s Punitive Expedition after Pancho Villa’s March 1916 terrorist raid on Columbus, New Mexico. During the course of their Indian Wars military encounters, 18 brothers in arms would be recognized for valor above and beyond the call of duty that resulted in the presentation of the Medal of Honor.

– Courtesy Anthony Powell Collection –

One reporter for an illustrated newspaper of the era summed up their indomitable fighting spirit. Writing for Harper’s Weekly about facing the Southern Cheyenne in Kansas, “embedded correspondent” Theodore R. Davis recorded, in now outdated, but highly descriptive, Victorian language:

“The Indians have come to regard a black man with holy horror. A body of them lately attacked Wilson Creek Station twice: each time a few colored troops were there. A few days since the savages made a third attack…. There was, indeed, only a small squad of soldiers, under the command of a colored sergeant, present; but they had nerve and showed it. As soon as the Indians were observed in the distance the sergeant led his men away from the Station up a ravine near which the Indians would pass if they intended to attack. As soon as the redskins came sufficiently near to be within easy range the black-skins rose and opened a rapid-fire from their breech-loaders. The Indians turned and fled, shouting, ‘Nigger! nigger! nigger!’ and ignominiously abandoned the field.”

In the process, black troops gained both laurels in battle as well as reputations as professionals, with many of the men making a career in uniform. They also earned a sobriquet that they themselves probably never used. An Army wife in Oklahoma, Frances Roe, wrote in her memoir in 1872, “The Indians call them ‘Buffalo Soldiers,’ because their woolly heads are so much like the matted cushion that is between the horns of the buffalo.” In 1889, when Frederic Remington’s article about these storied troops was published in The Century magazine as “A Scout with the Buffalo Soldiers,” the nickname gained nationwide notice.

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

Buffalo Soldiers would come to be seen as highly responsible, reliable veterans in spite of the often strict discipline they faced. A white sergeant serving in the ranks contemporaneously with blacks admirably recollected: “Accustomed to hard knocks all their lives, a little brutality on the part of an officer, more or less, did not seem to affect them either physically or morally, and their volatile, devil-may-care characters fitted them for the ups and downs of the army.”

Phrased another way, Civil War veteran Gen. John Pope, who continued to serve in the West, summed up the laudable record of black regulars in the West: “Everything that men could do they did.”

Additionally, the Secretary of War paid tribute to these stalwarts with the simple statement, “There are two regiments of infantry and two of cavalry of colored men, and their record for good service is excellent. They are neat, orderly, and obedient, are seldom brought before court martial, and rarely desert.”

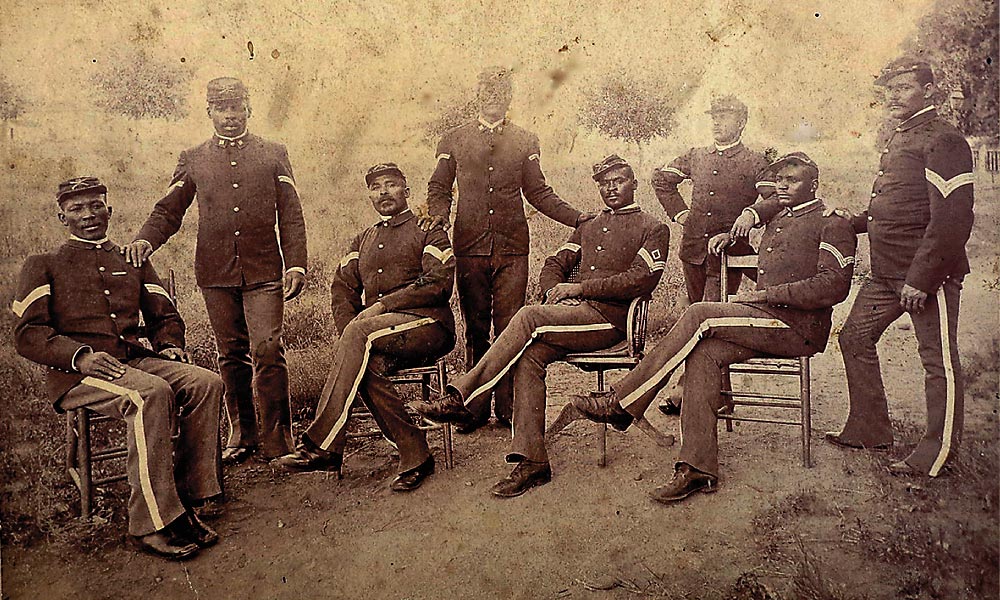

For future generations, black soldiers gained stature while setting a remarkable example through their perseverance under adverse conditions. They became role models and the stuff of legend. As Howard University’s distinguished faculty member Rayford Logan lauded: “Negroes had little, at the turn of the [20th] century, to help sustain our faith in ourselves except the pride that we took in the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry…. They were our Ralph Bunche, Marian Anderson, Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson.”

These Buffalo Soldiers made not only black history, but also American history. To borrow from a closing line in one of John Ford’s famed cavalry trilogy:

“…wherever they rode, and whatever they fought for, that place became the United States.”

– Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society –

Army Heroines

While Elizabeth Custer and other white frontier Army women who followed the guidon with their men have received considerable notice, the wives, daughters and mothers who accompanied black troops remain unsung heroines. As Rudyard Kipling so apply phrased it: “For the Colonel’s Lady an’ Judy O’Grady are sisters under their skins!” Little of these women’s stories about sharing the privations and bigotry of remote posts in the West have survived. Fortunately for historians, Vietnam-era U.S. Marine George Marshion of Vancouver, Washington, recently found an extraordinary cache of never-before-published provocative portraits taken at Montana’s Fort Missoula. These captivating 1890s images portray elegant late Victorian-era finery that signify these ladies were every bit the equal of the soldiers with whom they lived at garrisons located so far away from their places of birth.

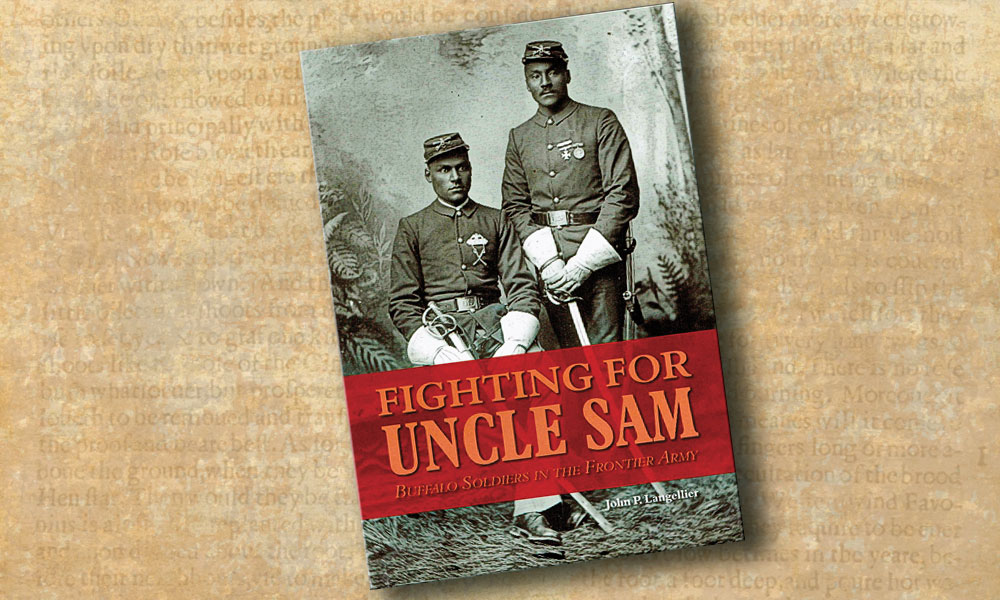

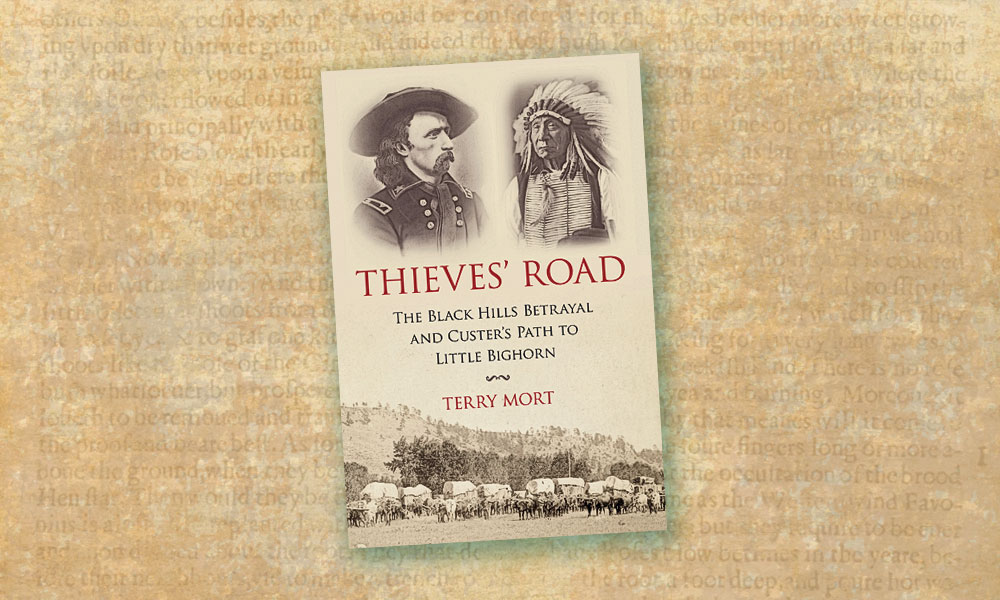

John P. Langellier gathered more than 150 images for his book published this year, Fighting for Uncle Sam: Buffalo Soldiers in the Frontier Army. Buy your copy today at

store.TrueWestMagazine.com