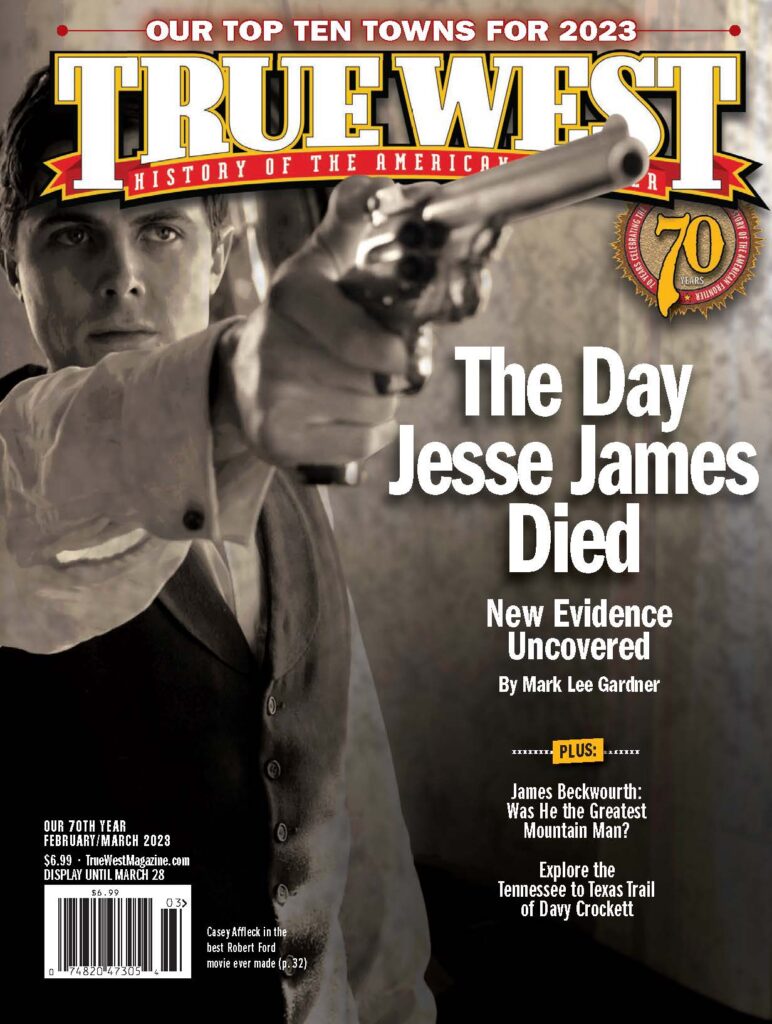

“I remember telling Ron once that I considered The Assassination of Jesse James as by far the best Jesse James movie ever made. He replied that he thought of it not as a Jesse James movie but as a Bob Ford movie.”

—Mark Lee Gardner, author of Shot All to Hell: Jesse James, the Northfield Raid, and the Wild West’s Greatest Escape

We recently got a chance to catch up with the brilliant writer Ron Hansen, who created the book that launched the movie that many of us consider the best Jesse James movie—and some of us maintain—the best Western, ever. Hansen has long claimed his movie is really not a movie about Jesse James, but about Robert Ford. Here are selected comments he made to us about his classic film The Assassination of Jesse James by The Coward Robert Ford:

TW: Did Angelina Jolie influence Brad Pitt’s decision to star in the film?

RH: “I’m told that when Brad Pitt decided to do my Jesse, at Angelina Jolie’s urging—she’s claimed it’s his finest acting

performance—Brad knew the first thing Warner Bros. would change was its title, so he had it written into his contract that my title would stay. And I also wanted it to reflect the cowardice that the media assigned to Bob Ford ever since 1882. Some reviewers were troubled by my use of the term “assassination,” since they thought it only applied to the killings of political figures, but readers of True West are aware that any shocking murderer was called an assassin back then. I liked the 19th-century idea of incorporating all the major incidents of a book into its title, such as the now-cropped front-page title to Pat Garrett’s The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, with its full, newspaper-like description for the uninformed of who Garrett and Billy were.

Courtesy Warner Bros./Ron Hansen

TW: Was there actually a four-hour cut of the film?

RH: “I’ve heard that cinematographer Roger Deakins loved a four-hour cut of the film, yet [director Andrew Dominik] denies such a cut ever existed. But I would not be surprised if Andrew’s original preview was far longer, because I saw a lot of fascinating scenes in the dailies that finally didn’t get incorporated. I also saw a cut that was 2:15, but too many intricacies were lost. The film is intentionally slower than we’re used to, both to increase suspense and, as director Ang Lee noted in defense of the pacing, to more fully represent an ambling, no-hurry sense of time in the 19th century.

TW: Did the film succeed financially at the box office?

Courtesy Warner Bros.

RH: “My information on the financials is not even as lofty as secondhand, but I’ve heard that it cost $30 million to film, even though Brad took far less than his going rate for his role in it. Warner Bros. seems to have made the decision not to push it, so it generally only lasted in a theater for a week before the copy was hustled off to another venue. The film did far better in England and elsewhere internationally, and it’s frequently available on streaming channels, so I suspect it’s earning back the cost to film it, even if it hasn’t been a big score for the studio. Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller fell flat in 1971, despite having Warren Beatty and Julie Christie in the leads, but a decade later, Altman said he was shocked to find out his film was considered a classic, an opinion shared by both Andrew Dominik and myself.

TW: Did you like the pace of the final cinematic release?

RH: “I was in a bookstore where employees were carrying boxes of the film’s DVDs and one stocker asked an-

other what the movie was like, and his pal disdainfully and ironically said, ‘It’s like reading a book.’ All the voice-over narration and, with just a few exceptions, the dialogue are indeed from my novel. The poetry in it is what attracted Andrew to the project, and probably Brad and Casey Affleck, whose stunning performance as Bob Ford made him a finalist for the Academy Award.”

Courtesy Warner Bros.

TW: Did Jesse James embrace his death? Was it, in fact a suicide?

RH: “Was Jesse James embracing his death? I do not think it was suicide, but he was a fatalist who’d seen the Younger Gang get wiped out in their Northfield, Minnesota, raid, seen others betray him and recognized he’d chosen a perilous profession and was now surrounded by wannabe miscreants he neither particularly liked nor trusted. So, 1882 was a year of cat-and-mouse in which Jesse James became a gangster consolidating his terrain and eliminating even potential traitors. He was ingratiating but disingenuous in giving Bob Ford the six-gun that would become the weapon in his own murder. He was pretending he completely trusted the kid in order to make him and Charley less wary. And then he operated by his own ethical standard, offering himself in perfor-mance as a defenseless, gunless friend who suddenly felt the need to dust a picture of his niece. Were they too cowardly to kill him then, Jesse felt he had the fair’s-fair permission to kill them later.”