Mi Buen Compañero

Beba agua mi buen compañero.

Agua fresca del cielo.

Beba para acariciar la sed.

Beba mi caballo alazán lucero

De esta copa, mi sombrero

Porque ya terminamos con

El trabajo del día.

Yo, y mi caballo que se llama

Bandolero!

—J. James Sánchez

Drink water, my good companion.

Fresh water coming from the heavens.

Drink to satisfy your thirst.

Drink my shining sorrel.

From this cup, my sombrero.

Because we have finished with

The work for the day.

Myself, and my horse, whose name is

Bandolero!

—translated

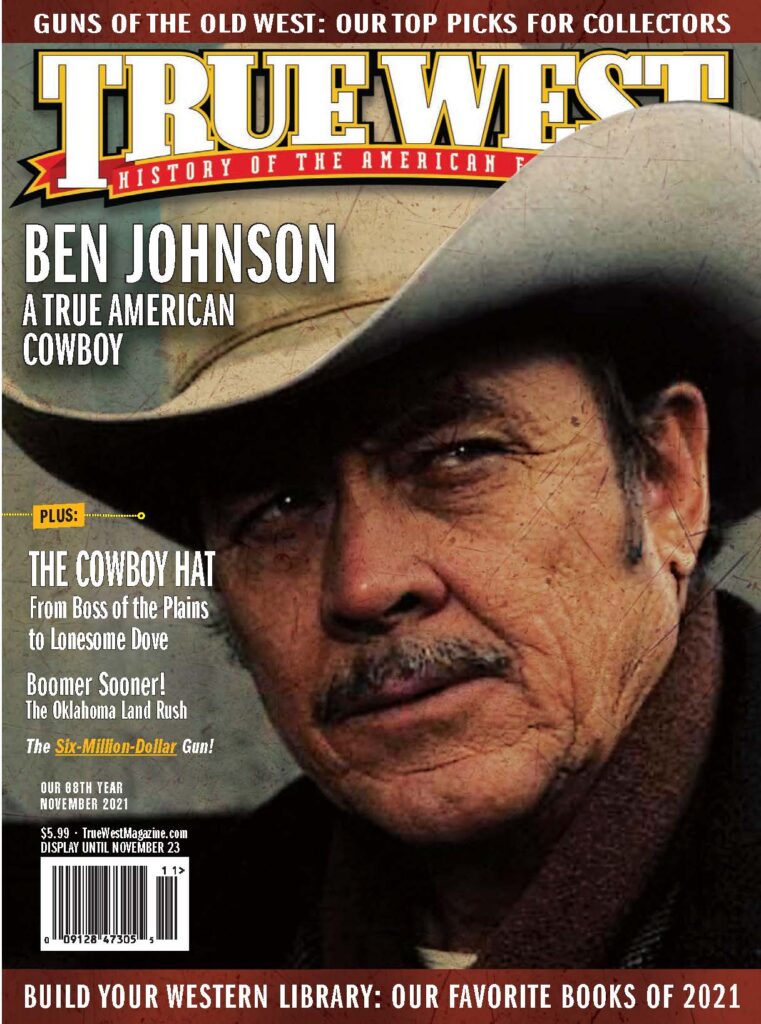

The legend of the Stetson goes beyond chivalry and the history of the Old West… It envelopes those of us who love the Western tradition, and those who were born to it as the vaquero, cavalry officer or cowboy and rancher.

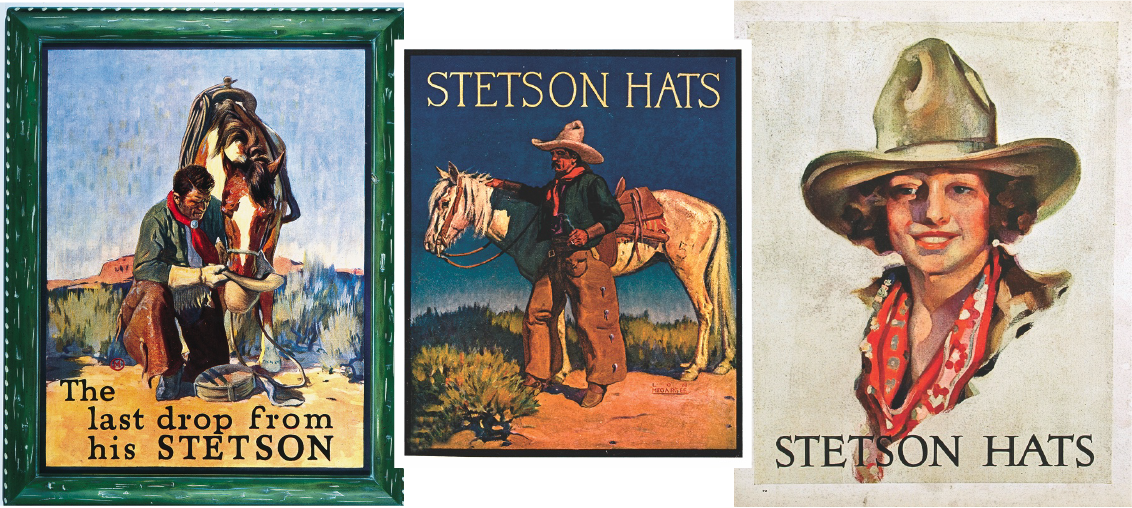

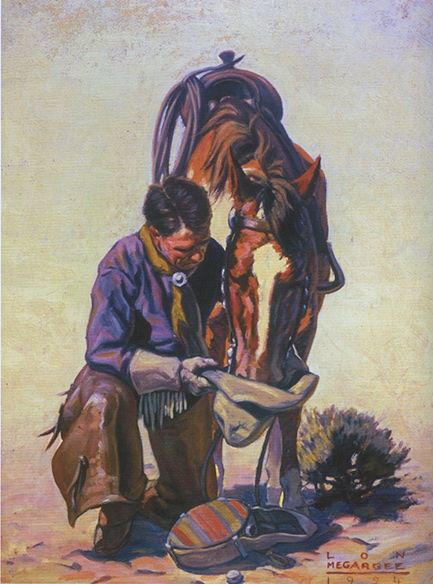

Stetsons represent more than 150 years of folklore, imagination, creativity and courage. Perhaps nothing embodies this more than the painting by Southwestern artist, Lon Megargee. Titled The Last Drop from his Stetson, it has become an icon, as has the hat itself, illustrating the respect and admiration the cowboy has for his selfless companion and partner, his horse. This painting is not only colorful but depicts a Western scenario emblazoned on our collective memory reminding us about our unique heritage—that Code of the West we all admire and try to live by!

Cowboys might not want you to know about their great affection for a mere horse, but in this painting one can see it, feel it, smell and taste it. Megargee captured and immortalized this image. The Stetson Hat company management was smart enough to “get it” and thus purchased the painting for advertising purposes. Little did they or the artist realize at the time how much a part of the American West that image would become. It still graces the inside of the Stetson.

Western imagery such as “from his Stetson to his boots,” or he “swept off his Stetson in a gallant gesture of bravado” or numerous other images come to mind. By the way a crease was made in those days, one could tell from whence came the man. There were sweat-soaked, working Stetsons, or Stetsons just simply meaning the cowboy hat. John Wayne wore them, so did Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson, George Bush, Franklin Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover and Ronald Reagan. Buffalo Bill Cody, Tom Mix, cavalry officers, the men of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and many others found them to be durable, practical in providing shade for the face from the unrelenting sun, a shield from wind and rain and a way to carry water or to provide one’s horse with a needed drink.

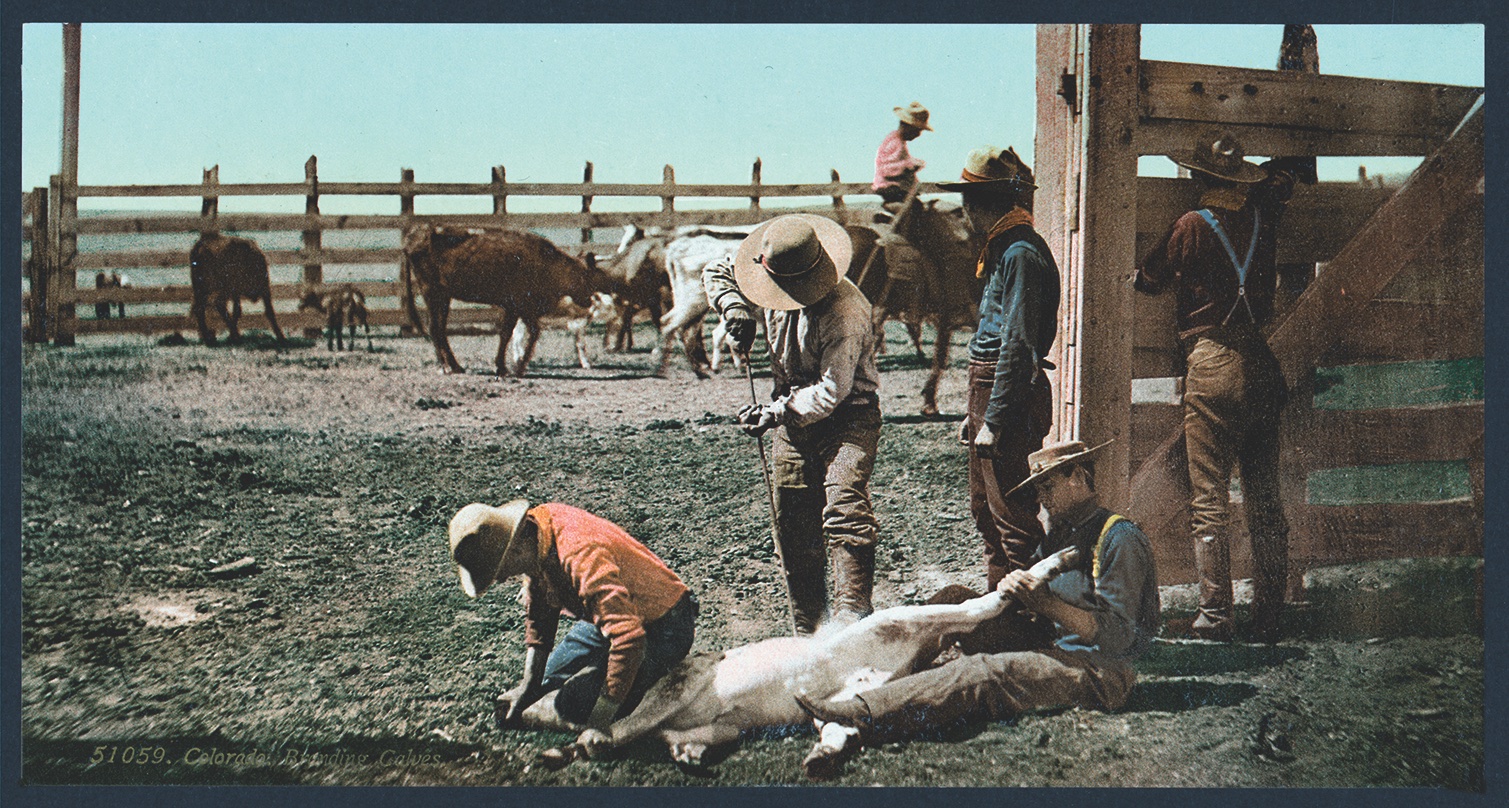

The working cowboy always fed and watered his horse first. A good rubdown was often given too as a special reward for a hard day’s labor. Thus, the act of offering water in his own hat that sheltered the cowboy from wind, rain and sun was the best tribute to indicate respect, admiration and, yes, even affection for a mere beast. Whether riding fence, chasing errant calves or wild steers through brush, mesquite or cholla or simply bringing the herd into another pasture, working with your horse was a spontaneous relationship marked by training and pride.

That same horse, given enough rest, would carry the cowboy into the roping arena. Calf-roping, bull-dogging and team roping encompass man’s best relationship with a trained animal. Sometimes even getting down and personal when the team won or failed, it was still done as a team. And part of the team look was, of course, the man, his saddle and his Stetson.

Stetsons in particular are also known for their style and class, but the word has come to mean in general, the cowboy hat, even though today there are many good brands of Western head gear. But where did the Stetson tradition begin?

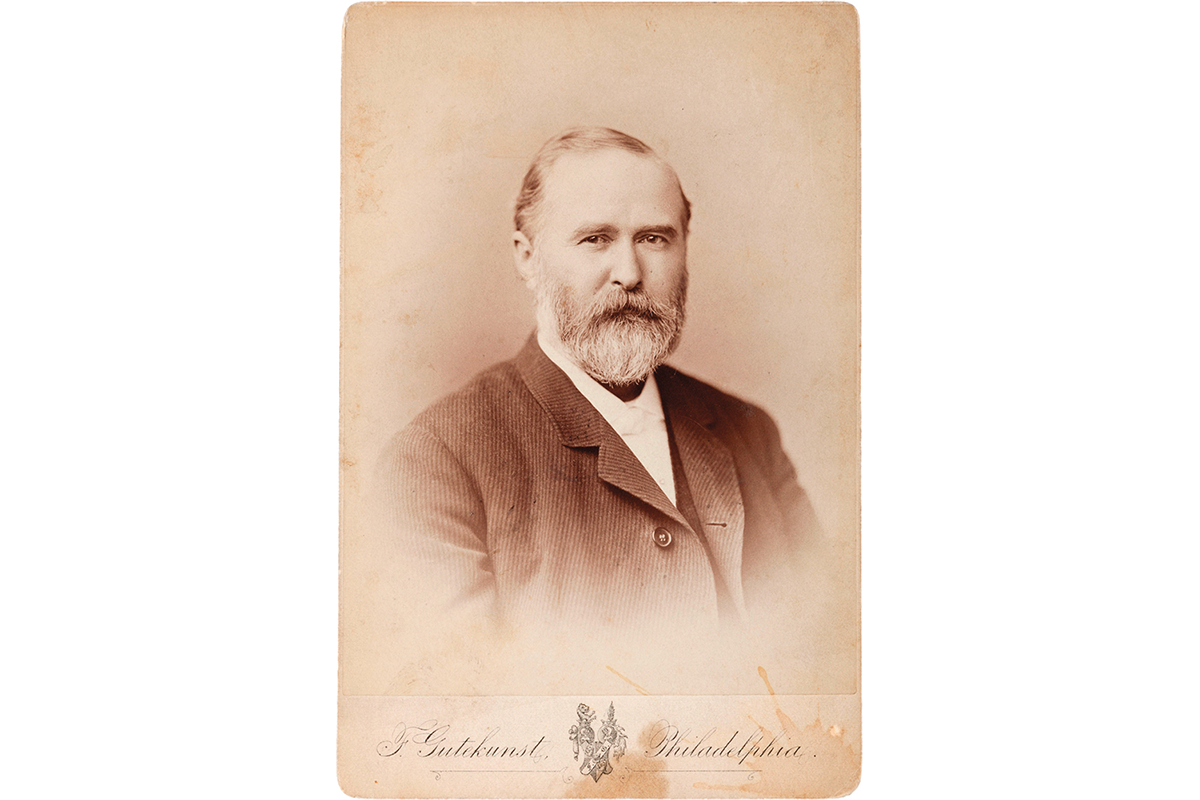

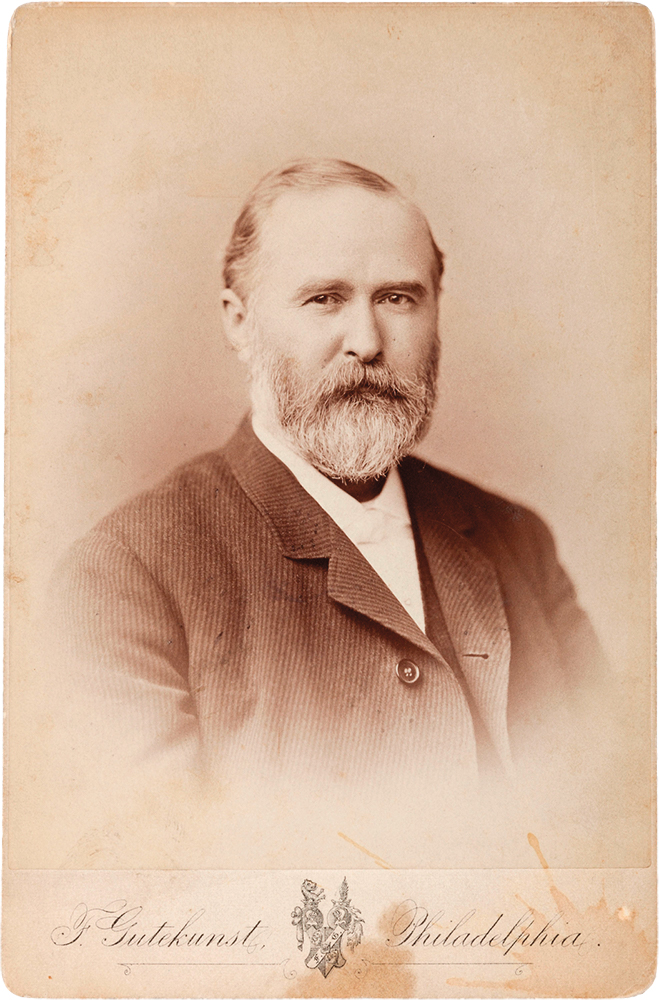

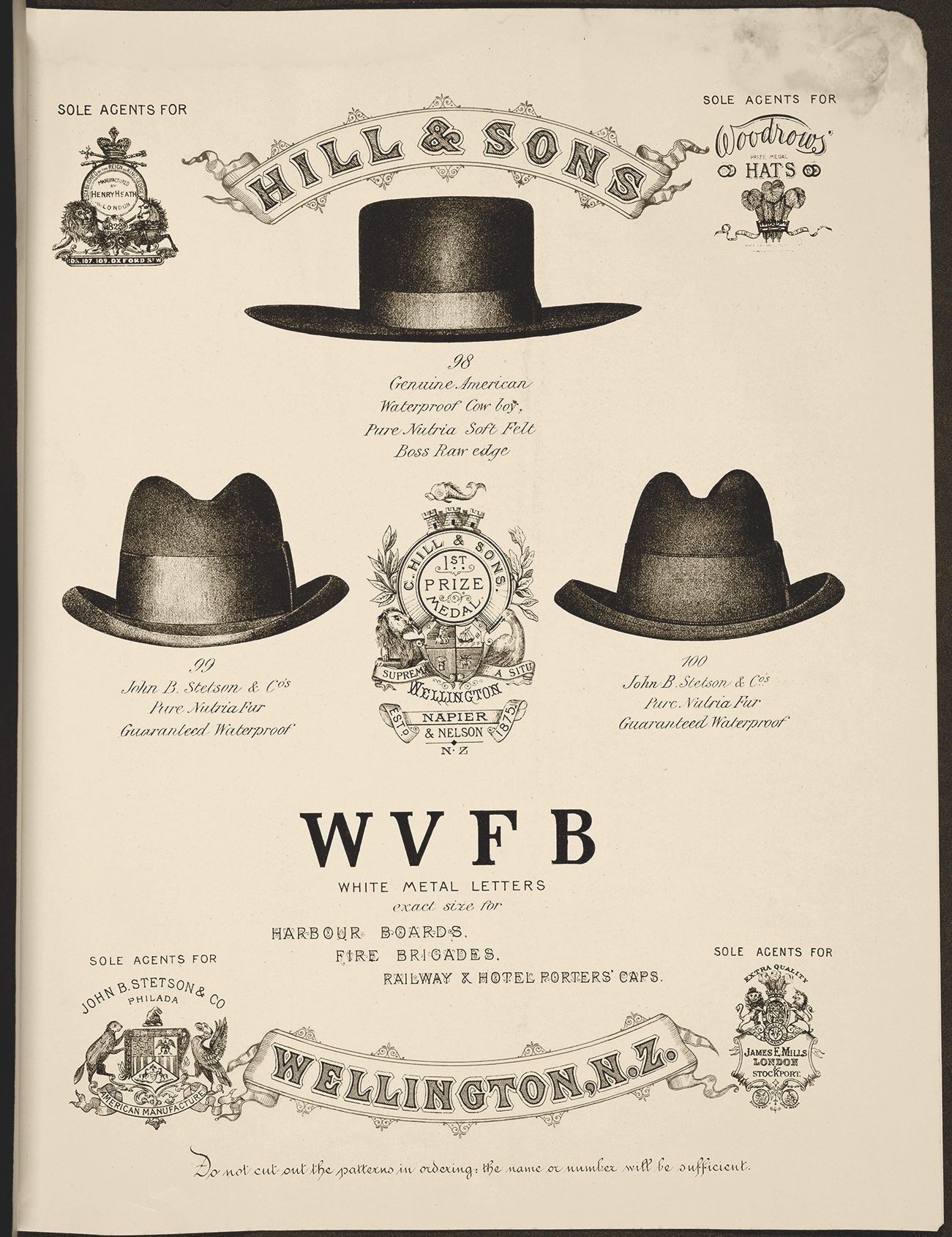

John B. Stetson (1830-1906) was born into a hat-making family in Orange, New Jersey. However, there was not enough room or profit for his entire family to make a living, so he decided to head out West. Additionally, his health was not the best, and he figured a change might not be a bad idea. He wanted to enlist in the military, but his health prevented that too. So his next move was to join a group of rough miners on their way to the Colorado goldfields. That didn’t last long but while in the field, weather was miserable and everyone was suffering from the elements. Because of his hat-making background, Stetson fashioned out of beaver fur a fine felt cloth that was waterproof and had a big brim for protection. It also had a high crown and waterproof lining. He called that first hat the “Boss of the Plains.”

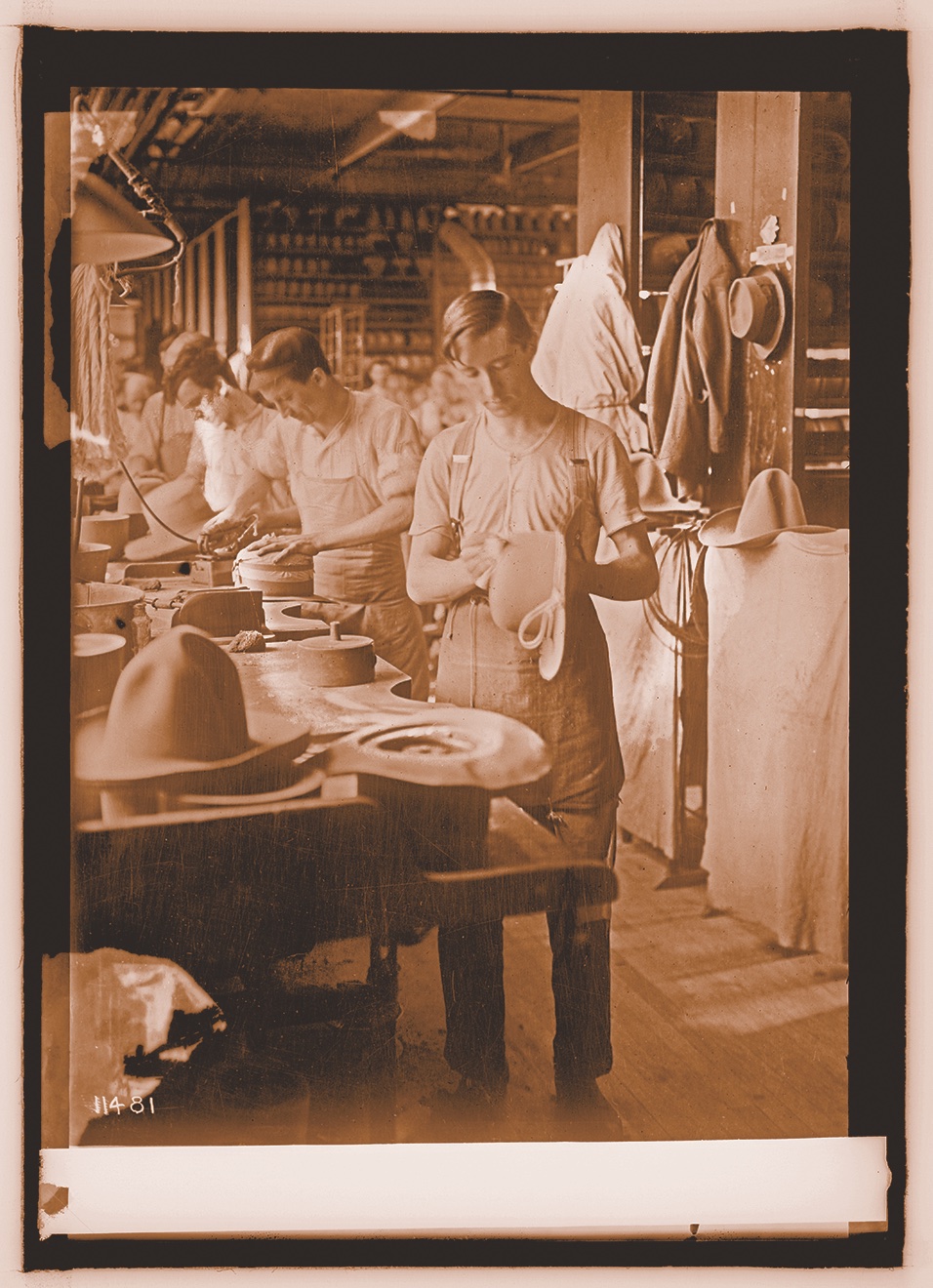

It became so popular that Stetson returned to hat-making, and by 1886 the Stetson Company was the largest in the world! He had also mechanized the hat-making industry. Because of his time on the plains and in ranch country, Stetson had seen what was required, and because of that firsthand experience, he knew what men wanted.

Another version says that the style really came from Christy’s Hat Factory in Frampton Cotterell, England. Even though Stetson’s design was adapted for the plains and mountains of the United States, the owners of the U.K. factory were so committed to their belief that he’d stolen their style that a lawsuit ensued. Stetson lost! However, as a hat-maker he would have had knowledge of different styles and purposes for hats. His adapting it to the way of the West is what is really important, and the rest is history because the Stetson tradition continues, and Christy’s is no longer even remembered in this struggle. The original Christy’s Factory today is a private residence.

Eventually, the Stetson Company did go out of business in 1971, and the name was licensed out to other hat companies. From the mid-1800s to 1971, had been a mighty good run, and the name today conjures up our image of the American West like no other. It does not really matter who designed the first prototype. We just know a Stetson when we see one.

And what about this “ten-gallon” hat ideal? That is yet another interesting trip into language and possible misunderstanding by early Anglo cowboys who often knew about and competed with vaqueros or Mexican cowboys. Listening to the musical language, they noted that vaqueros often referred to certain men wearing a particular hat as tan galan. This means “very gallant” or stylish. They interpreted it as “ten gallon,” and thus the image of a Texas cowboy in his ten-gallon hat looking dapper and ready for a baile (dance). Of course, a ten-gallon hat only holds three quarts, in case you were wondering!

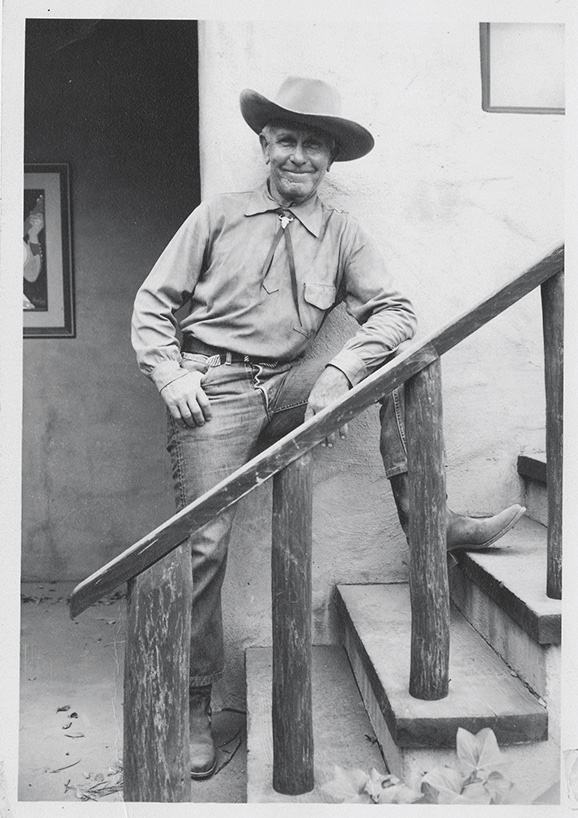

Lon Megargee, the Man Behind the Stetson Image

Although Lon Megargee resided in Arizona most of his life, he came through New Mexico on numerous occasions, especially visiting the artist colonies of Taos and Santa Fe. During the 1920s on one of his visits to Taos he was spotted at a fiesta dancing with Mabel Dodge Luhan, the well-known socialite and darling of New Mexico society. People saw the knife stuck in his boot as he whirled her around the dance floor. That made for good gossip for quite a while.

Born a dude in Pennsylvania in 1883, he remade himself as so many others had done when he headed west to become a cowboy. His trip westward was pretty much at the end of the “Wild West,” yet he created the image of a mythical and ribald character that made folks laugh, sigh, blush and long for the past. His many trips to Mexico, Spain and the Indian lands of the Southwest gave him a lot of material for his creative nature, and he became one of the best and most versatile of Southwestern artists.

In 1912, when both New Mexico and Arizona became states, Megargee was commissioned to paint the history of this transition in Phoenix. At about that same time, he also painted The Last Drop from his Stetson.

The Stetson Hat company purchased the painting and rights in 1923, after it was first published on the cover of Western Story Magazine. Lon did not get much for the painting, and he was almost always broke.

Lincoln County’s own Eve Ball had crossed paths with Lon before she moved to Ruidoso. Having purchased his guest ranch, La Casa Hermosa outside Phoenix, she became acquainted with and enchanted by this crazy cowboy artist. For a while he continued to live at La Casa, entertaining her many guests with his stories of adventures in Mexico and the Southwest. Once, he was captured by the soldados (soldiers) of Pancho Villa. He lived dangerously and never had any dinero, so the only way he stayed alive was supposedly by entertaining the men with caricatures of themselves. Eventually they let him “escape.”

According to Eve, she had learned that he traveled extensively and lived in Spain for a year. That time enhanced his interest in unpretentious structures because he loved the honest simplicity of the Spanish and Mexican homes and the manner in which they utilized the materials about them. Learning from Lon, Eve incorporated many of these same features in her own home in Ruidoso.

The five acres of land Lon purchased near the Arizona Biltmore in Phoenix soon became his comfortable Casa Hermosa (beautiful house), and Eve fondly described the huge hand-hewn beams that Lon had salvaged from an abandoned mine. The corner fireplaces were constructed with deep window seats. An interior patio and gardens, as well as ironwork of exquisite simplicity were also incorporated into the home.

Lon’s zest for life seemed to get him by the hard times. He was married to at least seven or eight women. The ladies could not resist the charm or the roguish smile. He was restless, independent and totally irresponsible. However, he was talented as hell, and until he died in 1960, Lon Megargee was one of the most colorful of our Southwestern artists—a real character never to be replaced.

And, yes, he wore many a Stetson!

Contributing Editor Lynda Sánchez and her husband, James, live along the beautiful Río Bonito in historic Lincoln, New Mexico. They raise corriente (roping) cattle and you can bet they have worn many a Stetson, too.