In his famous 1893 frontier thesis, Frederick Jackson Turner argued that the juncture between the civilization of East and the savagery of the frontier defined America’s image of itself.

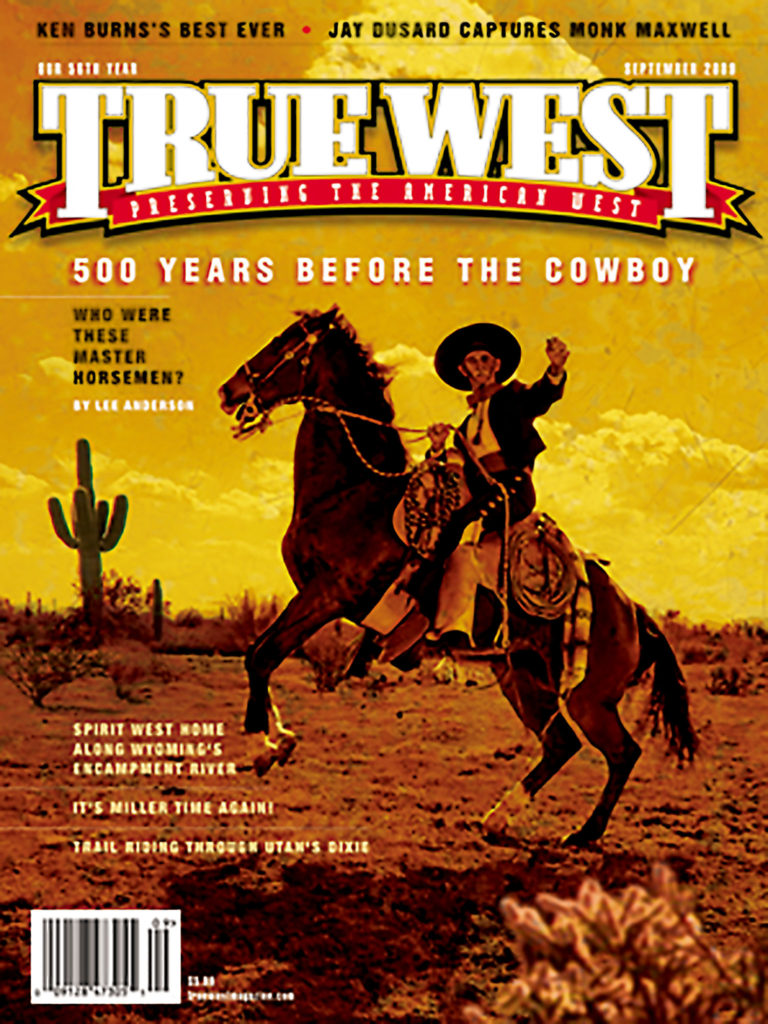

That may have been true, but one could argue that for the last 90 years or so the American character has been less defined by the realities of life in the Old West than by the Old West’s reflection in popular culture. That image is the subject of Edward Joseph Beverly’s Chasing the Sun, a veritable encyclopedia of literature of the West, and Michael Barson’s True West (no relation to either this magazine or Sam Shepard’s play), a pictorial history of Western films, TV shows and comics.

Beverly, a retired Army Corps of Engineers officer, has cast a wide net, one that takes in “genre” Westerns from Zane Grey, bona fide literature by Willa Cather and post-modernist fiction by writers such as Ivan Doig. The range is as vast as the country it covers, from the Spanish West (including selected reviews of Tom Lea’s The Wonderful Country, set along the Texas-Mexico border) to Alaska (Rex Beach’s enjoyable pot boiler The Spoilers).

You’ll read chapters on every conceivable Western subject. My personal favorites are “The Native Americans,” which resurrects the reputation of Dan Cushman’s hilarious Stay Away, Joe from an Elvis Presley movie, and “Wealth of the West,” which covers books on hunters of gold, silver and other treasures, and takes in the enigmatic B. Traven’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

Venerated authors have written several fine books over the years on the subject of Western fiction—Loren Estleman’s The Wister Trace sits on my shelf next to me as I write this—but nothing so comprehensive and insightful as Chasing the Sun. Beverly is a historian, but he’s also a pretty good critic. Here he is on perhaps three of the greatest classic Westerns (along with Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man) ever written:

Pete Dexter’s Deadwood: “Dexter’s Wild Bill is a doomed and subtly noble man, weary of living up to the legend as others wrote about him…wry humor coupled with a deadly seriousness is a distinguishing characteristic of Dexter’s style.”

True Grit, a cult favorite by Charles Portis: “The pleasure of reading the novel lies in Mattie’s narration and the dialogue. Portis uses late 18th century vernacular, an archaic formal way of speaking found in pioneer diaries that’s humorously out of place when used by Mattie and her rough-hewn companions….”

Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove: “Authenticity makes the novel an important piece of work. When writers use historical characters and back-grounds in their work, they often exaggerate the sensational at the expense of the credible. Lonesome Dove has its exaggerations, but McMurtry maintains a balance in presenting people as they could have been and events as they might have happened.”

The amount of work that went into writing this book is staggering to contemplate, and Beverly’s effort is clearly a labor of love—I don’t detect a musty whiff of the academic anywhere. If it’s colorful and reasonably authentic, Beverly likes it. Elmore Leonard’s “pulp” Hombre is a “thoughtful, absorbing western full of action—a tale of classic confrontation” with “characters sketched quickly but clearly.” Elmer Kelton’s 1980 novel about the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry, The Wolf and The Buffalo, has been much neglected by so-called serious critics. Beverly, rightly, finds it “A sympathetic picture of two opposing forces locked in a struggle to the death…. With sagacious insight, Kelton recounts the injustice that came with being black in a white man’s army.”

Beverly is also no snob when it comes to Western movies and happily tells you about the films made from the books he loves so much. I can’t help but think he’d enjoy Michael Barson’s True West: An Illustrated Guide to the Heyday of the Western, with a chapter, “Writers of the Purple Page,” which chronicles 100 years of literature on the Old West. (In the interest of full disclosure, Barson includes “Top 12 Novels of the Past 45 Years,” excerpted from an article I wrote for Salon.com.) You’ll also read chapters on the golden era of B-movie Westerns (take a bow, Gene and Roy), music (everything from the Bing Crosby-Johnny Mercer favorite “I’m An Old Cowhand” to Ry Cooder’s soundtrack for The Long Riders) and “The Great Western Comic Book Classics,” with two-dozen spectacular color plates from the 1950s and 1960s.

In fact, the range of the artwork included in True West is alone worth the price of the book. My own favorites are a poster from La Prisonniere du Desert—a.k.a. The Searchers—and the cover of a paperback, Poker According to Maverick (price 35 cents), with a sly Jack Kelly and even slyer James Garner. (I read that book when I was 10, but it never improved my poker game.)

Barson, a sharp-eyed and humorous observer of American popular culture, as proven in Better Red Than Dead and Teenage Confidential, grew up “In the sleepy (all right, let’s be honest—boring) post-industrial town of Haverhill, Massachusetts, during the Eisenhower fifties.” He received his indoctrination into Westerns through TV and old movies. “If I couldn’t be Rowdy Yates,” he writes, “I was willing to settle for being Sugarfoot … and if even being Sugarfoot was beyond my capabilities, then as a last resort I was willing to step into the shoes of Johnny Crawford”—Chuck Connors’ beloved son in The Rifleman. It’s a sentiment to which hundreds of thousands of us are able to relate.

You’ll want at least two copies of True West, one to leave on your coffee table and the other to cut out pictures of movie posters and book covers to frame. As the creator of Appaloosa characters Cole and Hatch, Robert B. Parker, writes in the introduction, Barson’s book is not about “the ‘real’ West, but rather the ‘true’ West—the mythic West. The one that matters now.” That sentiment applies equally well to Chasing the Sun.