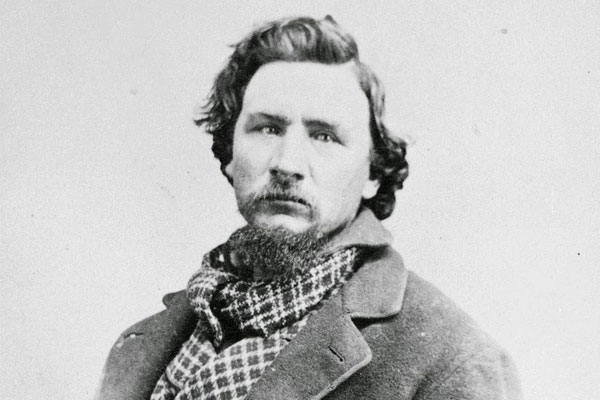

— Courtesy Crimson Forest Films —

You might guess that the worst single lynching in U.S. history took place in the Deep South and that the victims were black. But the remarkable truth is that it took place in the burgeoning California metropolis of Los Angeles in 1871, and its victims were 18 Chinese men and boys. That crime is the culmination of the story of The Jade Pendant, the Western film based on the novel by Hong Kong immigrant L.P. Leung. It’s a story he’s been wanting to tell for over 50 of his 80 years.

The Chinatown Massacre, wherein a gun battle between rival Tongs, over ownership of a girl, triggered the slaughter, is the film’s climax. But the plot is about the girl, Peony (played by Clara Lee), who flees China to escape a disastrous arranged marriage. Educated by her father in English and martial arts, she believes she’s sailing to Jin Shan—Chinese for “Gold Mountain,” their name for San Francisco—to work as a florist. She doesn’t realize she’s been sold to a Tong.

Leung explains that although men came from China to work in the goldfields or

on the Transcontinental Railroad during the 1800s, “[Chinese] women only came to America if they were forced to, sold to satisfy their father’s gambling debts. Those girls were shipped to America as prostitutes.”

Peony impresses the Tong brothel’s Madam Pong (Tsai Chin) with her literacy and intelligence, and becomes her pet. Peony meets Tom (Godfrey Gao), who has left the violent goldfields to open a restaurant and sell his invention, chop suey (Chinese for “leftovers”). They fall in love.

But when Madam Pong considers letting them marry, the couple learns that merciless Tong boss Yu Hing (Tzi Ma) wants Peony for himself, and all Hell breaks loose.

Leung well understands the plight of Chinese immigrants of the era. Although the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the only federal law ever to single out a race or nationality, was repealed during WWII, a quota remained until 1965.

“Only 108 Chinese were allowed to come to the United States a year,” he says. “In 1958, a missionary arranged a work study program so that I could come.”

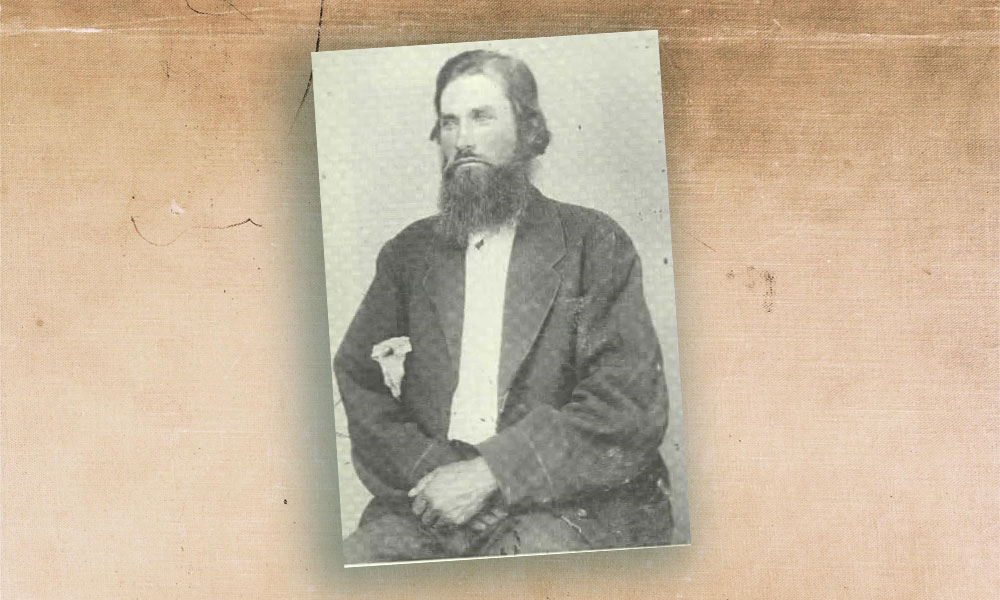

— Calle de los Negros photo courtesy California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California —

The son of a poor minister, Leung left Hong Kong for California with $35 in his pocket. He studied accounting and was hired by Paramount Pictures to track spending on various productions, including The Rifleman and Bonanza.

“Many scenes were shot on the Western street backlot,” he says. “I always enjoyed going over there to watch during lunch hours.”

He also tracked expenses and became friends with legendary Producer A.C. Lyles. “Do you know he used to be a mailroom boy at Paramount? From there, he got to know the stars. When he finally got a chance to make his own movies, he was able to call in his markers for some of those older movie stars. The main studios would not hire them anymore. A.C. could get them a week’s work for $10,000, making movies for less than $200,000 each,” he says.

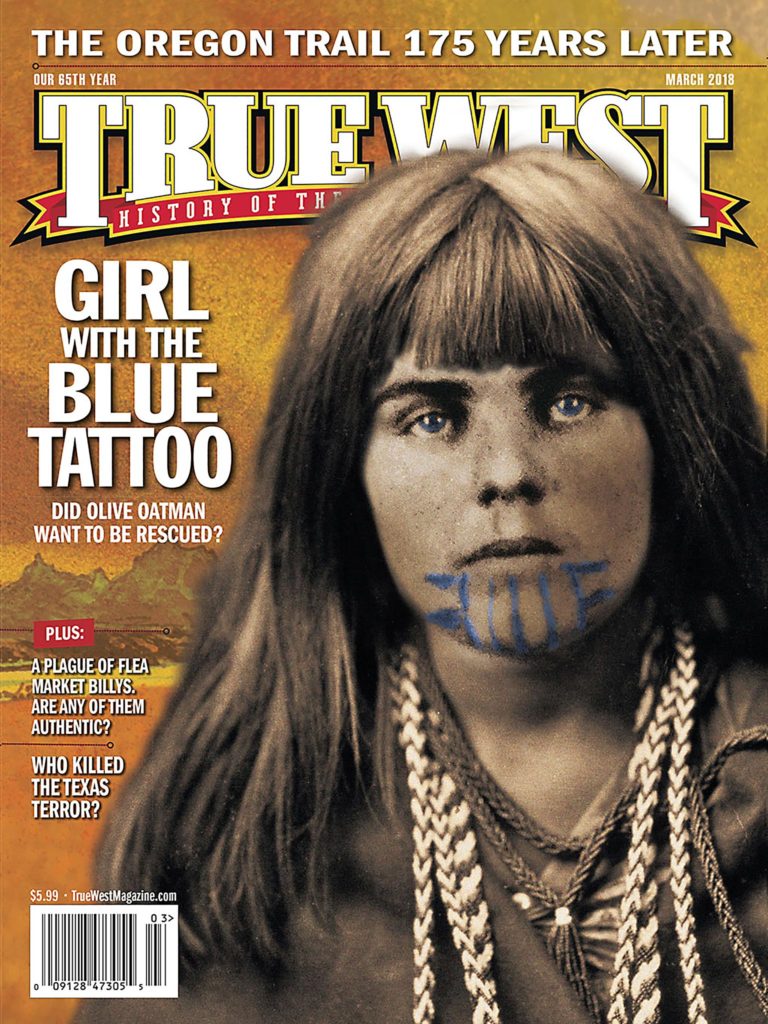

— Jail Yard photo Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Security Pacific National Bank Collection —

The primary market wasn’t Americans. “Japanese viewers loved cowboy movies with famous stars, even in their fading years,” he says.

The years at Paramount planted the idea of the movie that would become The Jade Pendant. “But A.C. kind of told me that America was not ready for what I wanted to tell,” he says.

In time, Leung wrote the novel and shopped it without success, until he was introduced to Producer Thomas Leong. “I gave him the screenplay, and I said, ‘If you’re interested, I want the movie finished in one year, because I’m not young anymore. I can’t wait.’ I met him in February. By June, we were looking for a director. We started shooting in September and finished in November, so it was all done within one year,” he says.

Despite his name, Director Po-Chi Leong is English, Leung says, adding, “And he did most of his work in Hong Kong. Even though he can speak Chinese, he cannot read Chinese. So, he was really at home with The Jade Pendant, because it was in English, with the Western and Eastern thing combined; he was kind of perfect.”

Of course, the modern-day cities of San Francisco and Los Angeles wouldn’t do for a period film. “We built a whole Chinatown near Salt Lake City, Utah,” he says.

Much has been written, some factual, some fanciful, about the mob that perpetrated the massacre and about the legal results: 15 were indicted, seven were convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to a range of two to six years, and none of them served a day, due to an atrocious technicality: that Dr. Gene Tong’s murder was never entered into evidence. The convictions were overturned; the charges were never refiled.

Before The Jade Pendant, little had been written about events from the Chinese point of view. The people of Chinatown didn’t write it, Leung says, “and [the press] did not have access into a Chinese community because they don’t speak Chinese, and the Chinese did not associate with journalists.”

Though a fictional version based on history, the story has now been told in this romantic, tragic and enlightening Western. If you missed seeing it in theaters, the movie will be out on DVD this May.

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com.