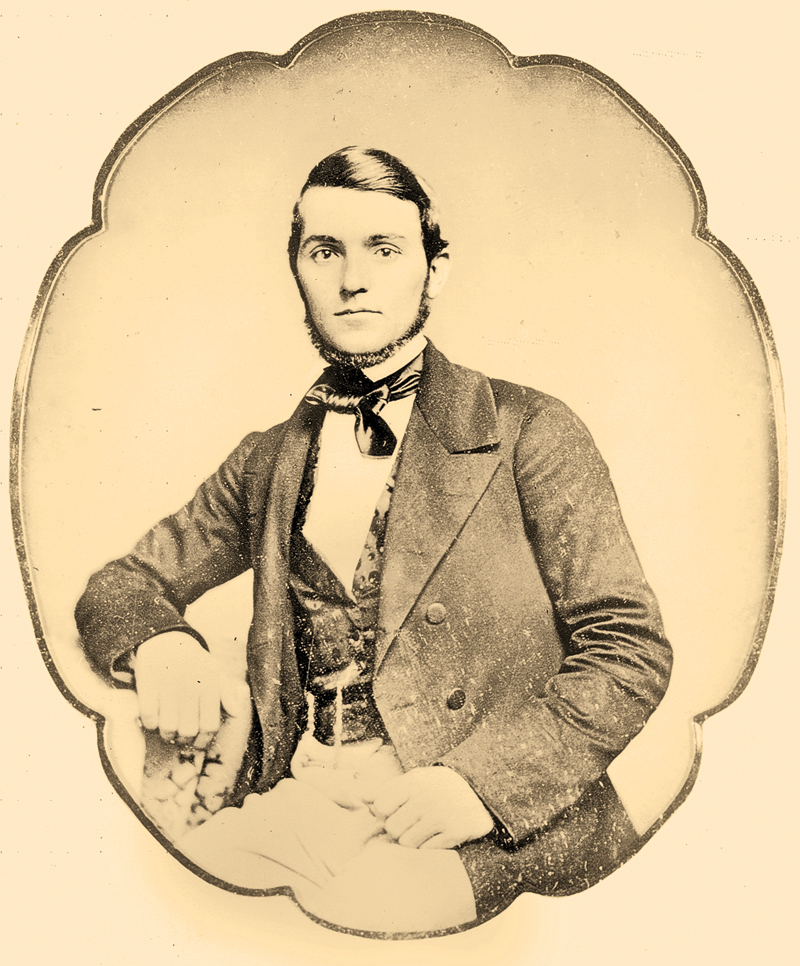

No more unusual story has emerged from Texas’s long and bitter struggle for independence than that of John Christopher Columbus Hill. The account of a boy’s fortitude and defiance in the face of almost certain death is all the more remarkable for being absolutely true.

Barely 13 when he first took up his rifle to face Mexico’s Army, Hill went on to graduate with a doctorate from one of Mexico’s most prestigious colleges, as the adopted son of Texas’s most implacable foe—Antonio López de Santa Anna.

The Christmas Day Mistake

Universally seen by Texians as the butcher of Goliad and the Alamo, Santa Anna, in 1842, made his bid to reclaim Texas for Mexico. The ink had dried on the treaty guaranteeing Texas independence six years earlier, yet, just a year after declaring himself dictator, Santa Anna set out to re-establish Mexican domain.

In response to the Mexican occupation of San Antonio and the seizure of Laredo, President of the Republic of Texas Sam Houston sent out a force of 700 volunteers, including two Texas Ranger companies. Joining the Rangers were Rutersville settler and San Jacinto veteran Asa Hill and two of his sons, Jeffrey and 13-year-old John. The Hill family had moved to Texas from Georgia in 1835, the year John turned seven.

Young and slight though he was, John had insisted on enlisting in the expedition. He carried the prized rifle that another sibling, James, had used to good effect at the Battle of San Jacinto while fighting alongside his father. “Brother John, this is not to be surrendered,” James had told him when he handed over the rifle.

As John rode away from the family cabin for what would prove the last time for many years, the teenager could not have predicted the extraordinary course his life would follow.

After re-capturing Laredo and Guerrero, the Texians moved on toward the town of Mier, 75 miles distant on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. By this time, nearly 400 of their number had left the expedition, including most of the Texas Rangers.

Ignoring reports of a large Mexican force under Gen. Pedro de Ampudia, the 261 Texians—including Asa Hill and his two sons—attacked Mier on Christmas Day, 1842. The Mexicans numbered an overwhelming 2,340.

An officer assigned John and a handful of other boys to a position overlooking a Mexican artillery battery, with orders to kill as many members of the gun crews as possible. This they accomplished

with considerable efficiency, killing some 50 soldiers.

Despite their short-term successes, the hopelessly outnumbered Texians were forced to surrender. They had reportedly killed more than 400 enemy soldiers and, in the process, suffered 10 dead and 23 wounded, including John’s brother, Jeffrey.

The Boy Captive

When the prisoners were ordered to turn over their weapons, John remembered his promise to his brother. “I saw some curb stones close by,” he later recalled, “which gave me an opportunity to break my rifle and throw it away.”

He was summarily brought before Gen. Ampudia to explain his actions. Haggard, ragged and filthy, tears of frustration scoring his dirt- and powder-begrimed cheeks, John believed himself about to be shot.

Ampudia, who had lost an adopted son in the battle, was surprised at his prisoner’s youth. John later recalled their exchange:

“Mi hijito,” the elegantly attired general said, “You are very young to be a soldier. Have the Texans so few men that they must send their little ones into battle?”

“I am no ‘little one,’” replied John, who had recently observed a birthday. “I am 14 years old.”

Queried as to why he had shattered his rifle, John replied that his brother had entrusted it to him on the condition that he never surrender it. “I have kept my promise.”

Asked if he had no father, John informed the general that both his father and wounded brother stood in the plaza among the captives. Ampudia mused aloud that the boy should be at home with his mother, to which John responded, “Sir, I came to take care of my father and Jeffrey. And today I have killed 12 of your men.”

The general closely questioned John about the number of men he claimed to have slain. John answered, “It may have been 15 that I picked off…but I am not sure of but 12.” He explained that he had been taught to shoot at an early age, and that “every one of us…learned to use a gun,” both for hunting and for protection against Indians, animals and brigands.

After verifying John’s claims, Ampudia had him bathed, fed and provided with clean clothes. John then delivered food to his father and injured brother. Seeing him in his new finery, one of the bedraggled prisoners observed, “You seem to have fallen on your feet, young man!” While some of the Texians resented the youth’s good fortune, his father and brother were greatly relieved to see him out of harm’s way.

Now known to his benefactors as Juan Cristobal Colon Gil de Ampudia, John was sent under guard to Mexico City. Before they parted, Gen. Ampudia wrote the boy an introduction to Santa Anna and gave him a fine horse and rig.

Ampudia ordered his men to deliver the boy directly to Santa Anna upon arrival in the capital. El presidente was ill, however, and John was temporarily lodged in the opulent palace of the archbishop, to await the dictator’s recovery.

Meanwhile, the remaining 243 Mier prisoners were force-marched through the harsh Chihuahuan desert toward Mexico City. In Salado, 181 of them briefly escaped; all but five were recaptured. Santa Anna peremptorily ordered death for all who had attempted to flee.

He then reconsidered and softened the sentence, by decreeing that only one in 10 should die. What followed was the famous episode known to history as the “Black Bean Lottery.” On March 25, each of the 176 escapees drew a bean from a clay pot; a white bean meant life, while those who drew the 17 black beans were shot. Asa Hill drew a white bean.

After the executions, the survivors were then marched the rest of the way to Mexico City and confined in Perote Prison. Jeffrey, who had not participated in the escape attempt, was too badly wounded to march and did not arrive in the capital until May, along with the other wounded Texians.

The Son of el Presidente

Awaiting his meeting with the dictator, John roamed the city unrestrained. At length, he was received by Santa Anna. “He was a rather handsome man,” John later recalled, “not tall, being only five feet five inches in height…. One would hardly take him for a dictator or tyrant.”

An enigmatic figure, the dictator could be as compassionate as he was cruel, depending upon mood and circumstances. John had no idea which Santa Anna he was meeting.

Fortunately for John, Santa Anna had read Ampudia’s report, and he made short work of the interview. “Now we will settle about young Gil. I want to adopt this boy and make a soldier of him.”

Without thinking, John replied, “Your excellency, I can’t be your son. I have a good father. And I can’t be a soldier in your country, because I am a Texian.”

Momentarily taken aback, the dictator let his anger cool before commenting. Turning to his generals, he smiled and said, “Our prisoner dictates terms!”

After conferring with his officers, Santa Anna determined on an alternate course: John would be sent to the Colegio de Minería (College of Mines).

John asked to speak with his father before responding to the offer. Asa, languishing in prison, considering John’s bleak prospects for advancement back in Fayette County, saw Santa Anna’s proposal as a brilliant opportunity for his young son. For his part, John leveraged his position into requesting the release of his father and brother.

Santa Anna complied. Asa and Jeffrey were released, provided with money and directed homeward. The boy then accepted the adoption proposal, on the condition that he never be required to renounce his country nor assume Mexican citizenship.

Sent to live in the home of Gen. José María Tornel, Santa Anna’s minister of war, John was treated “with parental kindness and equality within his family.” Santa Anna named Tornel president of the college that John attended.

The boy’s life became a whirlwind of activity, divided among classes, life at the Tornel home and visits and travels with Santa Anna and his wife.

Straddling the Border

John’s path, however, was not always an easy one. John’s loyalties were markedly strained during the Mexican-American War.

“That conflict was especially trying for me,” he later wrote. He understood the cause of his Mexican friends, some of whom died in the fighting, while he also felt a strong loyalty to the United States. One of the friends he made during the war was a young quartermaster named Ulysses S. Grant.

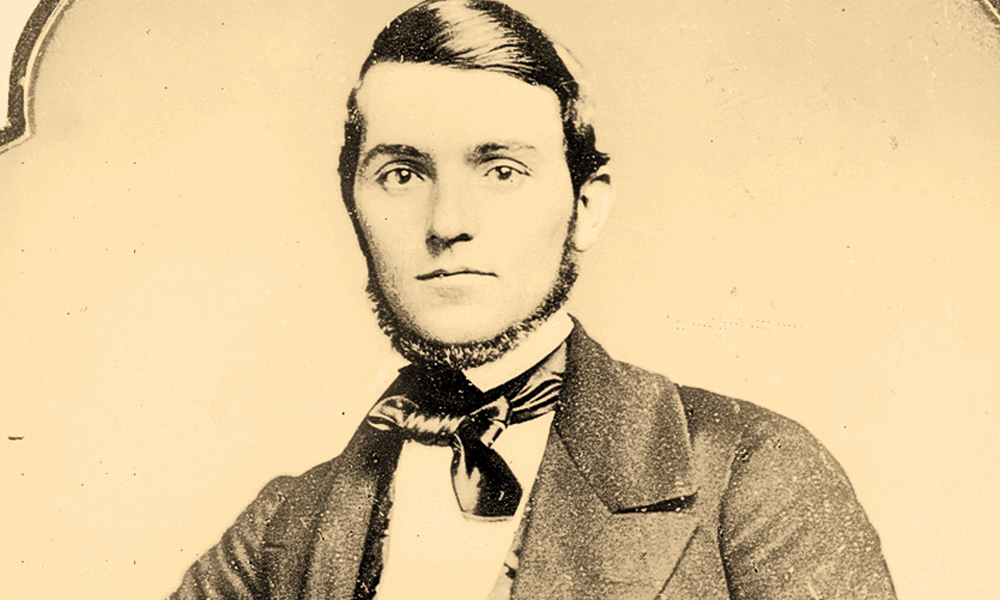

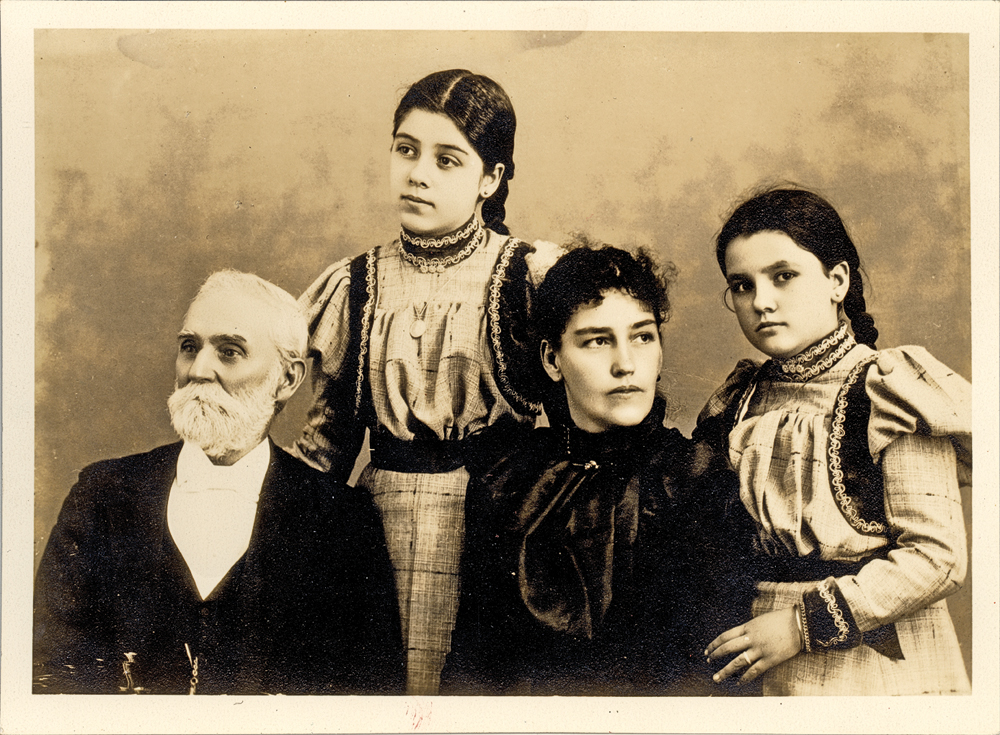

John graduated in 1850 with a doctorate in engineering and a degree in mining. He visited his family five years later to ask his mother’s consent to marry. By this time, Asa had died, and John’s mother had remarried. The scrawny volunteer who left home 13 years before had grown into a prepossessing young man whom one observer described as “modest and gentlemanly in his manner…[and of] irreproachable moral character.”

Maturing into one of Mexico’s foremost engineers, John designed a number of the country’s railroads and mining operations. He helped negotiate the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, held lofty positions in railroad and mining firms on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border and, in the course of time, built a significant personal fortune.

John married the daughter of a Spanish general in 1855 and sired four children. After her death 36 years later, he wed the daughter of an English immigrant. John died at the age of 75 while visiting his daughter in Monterrey, Nuevo León, in Mexico, and his body is interred in the city’s Panteon Municipal cemetery.

He never forgot his Texas roots and neither did the Lone Star State, which made him an honorary life member of the Texas State Historical Association in 1897.

Epilogue

Over time, some of the Mier prisoners managed to escape, but several died of wounds, disease and starvation. Santa Anna ultimately bowed to pressure from President John Tyler and released the remaining 107 captives. In the end, the only Texian to benefit from the ill-fated expedition was Juan Cristobal Colon Gil.

Ron Soodalter is a published author and magazine reporter who also writes a monthly column in America’s Civil War. He serves on the Board of the Abraham Lincoln Institute and is a member of the Western Writers of America and the Wild West History Association.