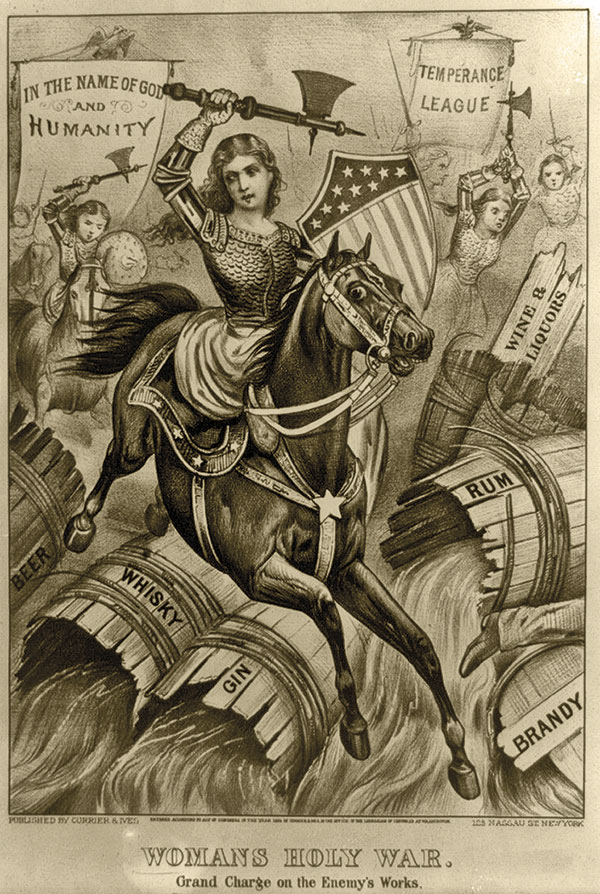

— True West Archives; Poster courtesy Library of Congress —

Carrie Amelia Moore, born in Kentucky on November 25, 1846, grew into a crusader

who chopped her way to legend as Carrie Nation.

In 1867, Carrie married Dr. Charles Gloyd, a drunk who destroyed the marriage and died in 1869, making his wife violently opposed to alcohol. In 1874, she married lawyer-journalist David Nation, a widower evangelist who preached on the evils of liquor. After the family moved back to Medicine Lodge, Kansas, in 1889, Carrie organized a local chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

During the 1880s-90s, in Kansas, Missouri, Texas and Oklahoma Territory, she and her colleagues marched into saloons, sang hymns and read scriptures, and harangued the clientele. When asked to leave, they did so without arguing or violence.

Feeling like she wasn’t getting anywhere, Carrie did what she always did: turned to the Lord. On June 5, 1900, she got an answer, as she recounted in a later edition of her 1904 autobiography, The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation: “I was impressed with a great inspiration…. ‘Take something in your hands, and throw at these places in Kiowa and smash them.’”

Carrie went to Kiowa, on June 7, 1900, to Dobson’s saloon. She announced, “Men, I have come to save you from a drunkard’s fate,” and then hurled rocks at the liquor bottles behind the bar.

Her husband provided her trademark hatchet a few months later, so she could cause maximum damage. “That is the most sensible thing you have said since I

married you,” she replied. She divorced him the next year.

Carrie carried on her sharp-edged work for the next decade. She was arrested about 30 times and spent untold sums on fines and legal fees, paid for by lecture fees and sales of souvenir hatchets. She traveled the country with her message about the demon rum and liquor, and made headlines wherever she went.

Yet Carrie’s interests went beyond temperance. On holidays, she fed the poor and homeless. She sewed clothing for the needy. She campaigned for women’s suffrage. And she served as caregiver to her mentally-ill mother and sister.

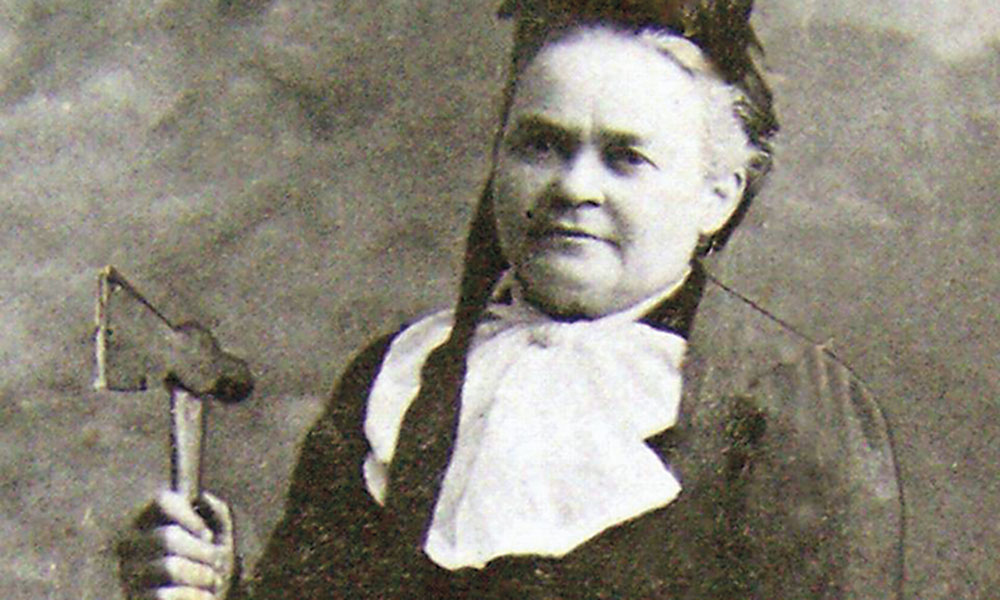

That history remembers Carrie and her hatchet is due, largely, to her. She knew the value of publicity. She appeared in vaudeville and music halls, went overseas, started newspapers (including one called The Hatchet).

Six months after collapsing during a speech, Carrie died on June 9, 1911. She didn’t live to see the 18th Amendment ban booze in the U.S.—or the 21st Amendment that repealed Prohibition. But that image of the little old lady, dressed in black, a Bible in one hand and a hatchet in the other, is one that still resonates nearly 120 years after her first saloon attack.