In 2010, shortly after the first publication of my book To Hell on a Fast Horse, I learned that New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson was again giving serious consideration to granting a posthumous pardon to Billy the Kid. Billy had been promised a pardon by then-governor Lew Wallace in exchange for his testimony before a grand jury investigating a murder Billy witnessed. At great personal risk to himself, Billy gave his testimony, but the pardon never came. If Wallace had indeed wronged Billy by not issuing the pardon, Richardson wanted to make it right before he left office at the end of the year. Too late for Billy, of course, but not for history buffs the world over.

I broke the story of the potential pardon for one of the Old West’s most famous outlaws with an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times. “A deal is a deal,” I argued then, half playfully, “and 129 years doesn’t change that. Billy is owed a pardon.” The news of what Richardson was considering raced across front pages and Internet browsers faster than a bullet from Billy’s Colt Thunderer, and with it came considerable controversy.

Soon the New York Times asked fellow author Hampton Sides for his opinion, and Hampton, who lives in Billy’s old stomping grounds of New Mexico, didn’t hold back. He referred to the Kid as a “thug” and a “trigger-happy sociopath.” “What’s to be gained,” Hampton asked, “by dredging up stories from a tired old shoot’em-up?”

Hampton was by no means the only Billy hater out there. The descendants of Sheriff Pat Garrett were also strongly opposed to a pardon, which they believed would diminish their ancestor’s unrelenting efforts to bring law and order to southeastern New Mexico Territory. It was a good argument, but the posthumous pardon was about symbolic justice for Billy; it couldn’t and wouldn’t erase Garrett’s heroics as sheriff of Lincoln County.

Finally, on the last day of 2010, Governor Richardson announced his decision—live on national television (which tells you just how big the pardon issue had become).”I’ve decided not to pardon Billy the Kid,” the governor told his hosts on ABC’s Good Morning America, “because of a lack of conclusiveness and the historical ambiguity as to why Governor Wallace reneged on his pardon.”

Richardson’s decision was certainly a disappointment for the romantics among us, but the months-long saga did prove Hampton Sides wrong about one thing: the Kid’s story was anything but “tired.” And ten years on, it shows no signs of letting up. (Sorry, Hampton.) A case in point, I’m happy to say, is To Hell on a Fast Horse, which has gone through multiple printings and now a special 10th anniversary edition.

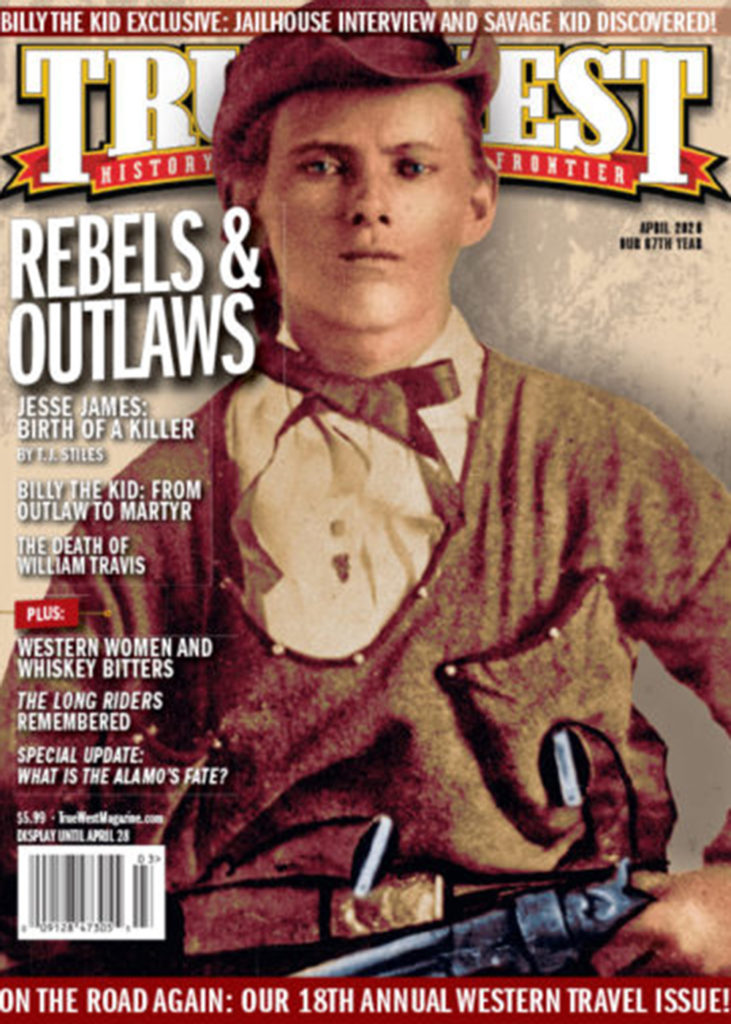

Not a year passed since my book first appeared, it seems, that the Kid didn’t make headlines. In June 2011, the only surviving authentic photograph of the outlaw, a tintype, sold at auction in Denver, Colorado, for $2.3 million—the presale estimate was $300,000-400,000. It remains the highest price ever paid for a 19th-century photograph. I was at the auction and had the privilege of looking Billy square in the face, so to speak, before the rare image passed into the private collection of the winning bidder, billionaire and Old West enthusiast William I. “Bill” Koch.

A predictable result of the tintype sale was the sudden appearance of a number of historic photographs purportedly picturing one Billy the Kid that had been scrounged from flea markets, antique shops and eBay. With stamps of approval from self-proclaimed photo “authenticators” using controversial facial recognition technology, each new “discovery” was touted by the press, and the owners of the images naturally believed they’d hit the jackpot. In 2015, the National Geographic Channel even featured one of these images, a tintype said to picture young Billy playing croquet at a genteel outing with his friends, in a 90-minute documentary broadcast internationally.

Despite all the hoopla, not one of these wannabe Kid photos has passed muster with knowledgeable historians, myself included. And while I do believe it’s likely that Billy stared down the lens of a box camera more than once in his 21 years, any historic photo put forth as a portrait of the Kid cannot be based on resemblance alone. It must have a rock-solid provenance linking it to the outlaw. Otherwise, it can never be anything more than a picture of a goofy-looking juvenile that looks a little like that fuzzy, dim portrait of William H. Bonney.

Of course, my book is just as much about Pat Garrett as it is the Kid, and I had thought my unconventional take (i.e., sympathetic) on the once-revered sheriff might help to rehabilitate his tarnished image. But there are many who continue to have a negative view of the man forever known for gunning down young Billy. In 2018, the Doña Ana County Historical Society proposed that a Las Cruces, New Mexico, street be renamed from Motel Boulevard (which boasted only one motel) to Pat Garrett Boulevard to honor the county’s most famous lawman. Their proposal didn’t get very far with the City Council, however. One councilor was quoted as saying that naming a street after “a white symbol of the Old West” was “very offensive to me.” The boulevard continues to honor that lone motel.

Numerous articles and books touching on the Kid or Garrett have been published since To Hell on a Fast Horse first appeared, but if I were rewriting my book today, there would be no changes to my narrative, simply because no previously unseen primary sources have come to light that would necessitate a change. I should, however, provide an update on one item: the lawsuit over Billy’s possible DNA and its analysis. After an enormous amount of time and money spent in the New Mexico courts, the official lab results were made public in 2012, which revealed that the blood samples tested (whether or not they belonged to the Kid remains unknown) did not have enough DNA to generate a good sequence. Other than it being a win for the Freedom of Information, the result of all the legal wrangling was a letdown for Billy buffs.

I’ve written other books since To Hell on a Fast Horse came out, but I continue to be passionate about the Kid and Pat Garrett. For me, their story remains thrilling, tragic and irresistible—worthy of the telling in the 21st century. And I trust the two will continue to gallop across people’s imaginations in the 22nd century as well—at least I hope so.

I wonder, though, how many more photographs of Billy the Kid we’ll have by then….