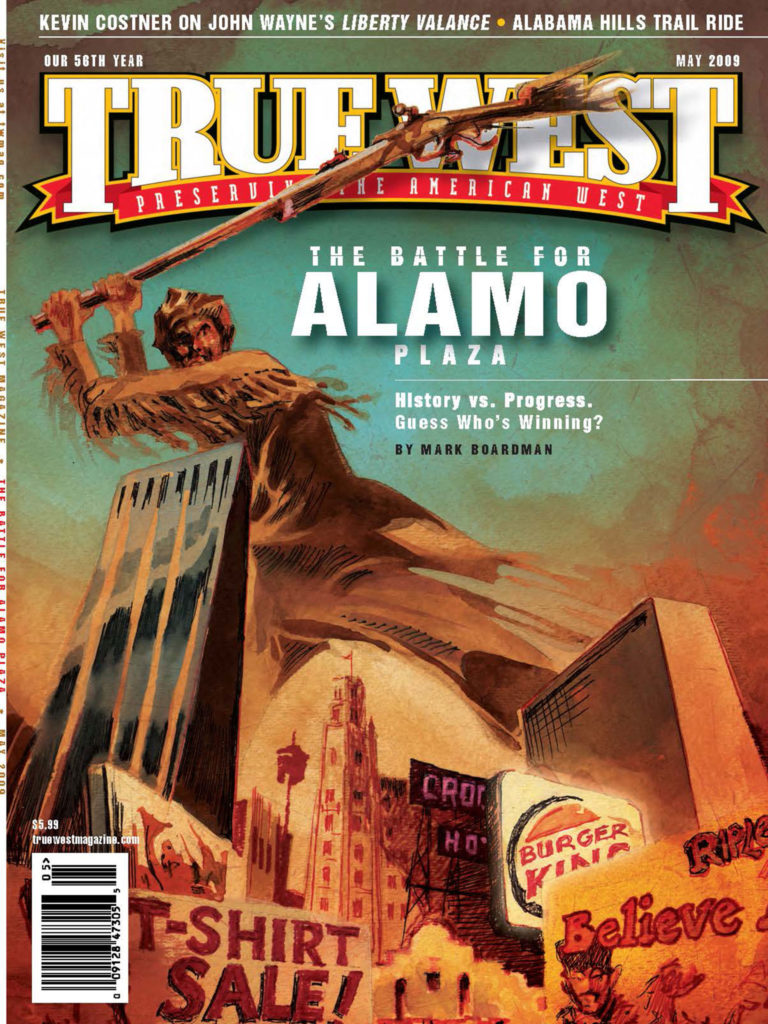

It’s a chilly afternoon, with a hint of rain in the air of San Antonio, Texas.

I’m walking the streets, taking in the sights and sounds. I pass by an old block of buildings, filled with t-shirt and novelty shops. The Guinness Book of World Records attraction is right next to the Ripley’s Believe It Or Not haunted adventure. Music blares, weird mannequins grab the attention and garish colors overwhelm.

But my mind isn’t taking all that in. I’m imagining that same space, 173 years earlier, when more than 200 brave men died defending an old mission.

On this spot, their leader, Col. William Barret Travis, had his headquarters. Just north of where I’m standing, in what’s now the lobby of the U.S. Post Office, he died during the early part of the battle.

Most of the folks who are walking by Guinness’s or Ripley’s don’t know it, but they’re in the Alamo.

Who Knows?

I’m not an expert on the Alamo, not by a long shot—not the battle, the buildings, the preservation, the literature, whatever. So on this day, I need some help; it comes in the form of Alamo Curator Richard Bruce Winders and Dorothy Black, a member of the Alamo Committee of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT), the group that oversees the landmark.

Their first point: Most folks don’t know the Alamo. We’re standing outside the front door of the church, looking directly across the street, as Winders explains, “If you look to the west, you see the Crockett Block of buildings that dates back to the 1880s; you’re looking at where the old west wall was. If you’re looking to the north and see the Post Office, you’re looking at where the old north wall was. If you know that, you can see these indications. If you don’t know that….”

But there’s nothing that tells anyone. No printed information available at the church. No signs or plaques. An audio tour includes some of the information, but most visitors choose not to take it.

We walk south, to the front corner of the church, where a diagonal line of walkway stones heads out into the Plaza. Most folks don’t see the pattern because it doesn’t really stand out. “Do you know what that is?” Winders asks. I have no idea. “That’s where the low wall stood in March 1836,” Dorothy explains. “Davy Crockett and his Tennesseans manned that position.” They were basically fighting at ground level with little cover—not the scene from Disney’s Davy Crockett where Fess Parker is swinging his rifle like a club from the parapets. If Dorothy and Bruce hadn’t pointed it out and explained, I’d have never known.

We continue walking as Dorothy goes back inside, continuing her preservation work on the church. Winders and I head southeast, on Commerce Street, an area that’s not near the River Walk or the Alamo or any of the old missions—in other words, it’s off the beaten path. We come to a stone wall with a couple of signs on it: this is where the Mexicans burned the bodies of at least some of the Alamo defenders. It’s generally believed that somewhere around here—nobody knows for sure—the ashen remains were buried. Few visitors ever come here.

“But this should be hallowed ground,” I say. “There should be more here to honor the dead.” Winders agrees. “This is owned by the city, and most city officials don’t know about this site,” he explains. I’m stunned as we walk back west, beyond Alamo Plaza, and to the pedestrian plaza.

Here is where the Texians drove out Mexican forces in 1835, effectively declaring war. It’s where Santa Anna was headquartered during the Alamo siege, where he raised the flag of no quarter. Some still believe that the Alamo defenders’ remains are interred at the Plaza’s San Fernando Cathedral. The city is renovating this area, making a pedestrian park (similar to what many preservationists want at the Alamo) with a fountain, intricate stone walkways, landscaping, that sort of thing. The city is pumping a lot of money into this—the original $12.2 million budget will probably double by the time everything’s finished. Yet there are no signs that explain the history of this site, save for a small plaque on the cathedral.

How will people who come here—visitors and San Antonio residents—learn about the amazing history of this place?

And how did the Alamo get to this point?

The Road to Misunderstanding

Alamo historian Alan C. Huffines says it comes down to ignorance. “City officials think it’s already preserved,” he says. “Because the iconic emblem is preserved—the church, and the first story of the convento.”

DRT member Dorothy Black—a native San Antonian—agrees: “One reason that the city tends to ignore Alamo Plaza is that it is a political nightmare for elected officials.”

Of course it is. Look at the groups that have an interest in the Alamo—the feds, the state, the city, local businesses, the DRT, historians, preservationists. Getting everybody on the same page? It’s hard enough to get them in the same book.

Mark Lemon, author of The Illustrated Alamo 1836, says another factor is location, location, location. “The Alamo has suffered from its proximity to the town, which grew up all around it in an era before the term ‘historic preservation’ really meant anything.” As a result, the outer walls were buried under buildings. The exact location of the defenders’ remains was forgotten. Visitors to the church and convento often ask, “Is that all there is?”

Popular culture hasn’t helped much. Disney’s 1950s TV show and 2004 movie wrongly played up the church as the central location of fighting. So did the John Wayne flick from 1960. Heck, the famous hump wasn’t even built until 1850, 14 years after the battle. But for most folks, that rounded church peak is the symbol of the battle. That’s what they come to see—not the original outer wall sites in the Plaza.

Without better interpretive markers, signage or maps, the misconceptions continue, generation to generation, only strengthened with the passage of time.

Alamo Accolades

In all fairness, some progress has been made at the Alamo site. In 1977, the National Register approved the Alamo Plaza Historic District. The next year, the San Antonio City Council took a similar action for the Plaza and surrounding area.

In 1985, an exhibit on the history of the Alamo was installed in the convento’s Long Barrack Museum.

In 1994, the street directly in front of the church—Alamo East—was shut down to traffic. An Alamo Plaza Study Committee was set up to consider future development in the area. The Wall of History was installed in 1997, another exhibit telling the story of the Alamo.

Last year, the Alamo debuted a 55-minute audio tour of the facility, complete with narration, sound effects, music—and a historically accurate portrayal of the battle.

The website TheAlamo.org does a great job of covering the history—including the Plaza and the important locations, such as the funeral pyres and San Fernando Cathedral, associated with the battle.

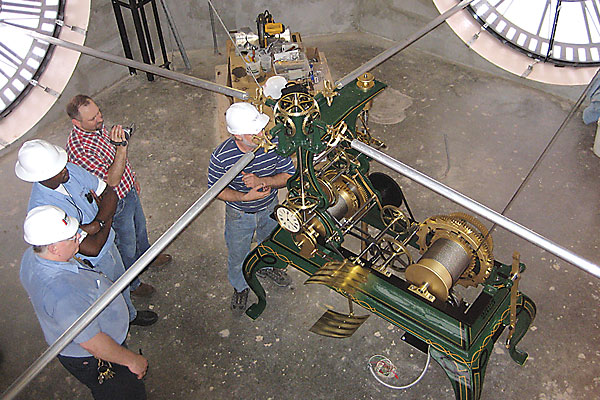

The Daughters of the Republic of Texas have dedicated themselves to preserving the structures—painstaking work that can involve using toothbrushes and materials to remove hand oils and groundwater salt from the walls of the church.

The pop culture aspect of the place (which once included the coonskin cap worn by John Wayne in his movie of the Alamo) has been diminished; real history is emphasized. But even curator Bruce Winders admits that “there is still room for improvement”—especially in the Plaza.

Solutions?

What’s to be done to make the site the best it could be? Ask 10 people, and you’ll probably get 10 different answers. The most ambitious plan comes from Gary Foreman, a Chicago-area based film producer. He’s been one of the most vocal and high profile proponents in the field of Alamo preservation for 27 years. Foreman wants the entire Plaza redone to reflect the 1836 mission—a project that would close the remaining streets, tear down the Crockett block of buildings and rebuild the old walls, plus convert the post office into a multimedia, high tech interpretive center. The Foreman project is as controversial as it is big.

Others have more modest plans. The starting point for those: Getting rid of the traffic. “You take your life in your hands when you cross the two streets around the Alamo,” Huffines says. “We could decide that we’re not going to move any buildings and just shut those streets down, and it would improve things dramatically.” Mark Lemon agrees, “Every day, thousands of cars buzz right through the interior of the compound where Texas’s greatest heroes bled and died defending their rights. That in and of itself is outrageous and disrespectful.”

Curator Bruce Winders concurs that closing the site off from street traffic “would help reinforce the impression that this is a special area. Which would then help with the interpretation of the space.”

If the streets were closed, then the entire area could be converted into a pedestrian plaza, with historical markers. The carnival atmosphere generated by the Crockett Block businesses may not entirely disappear, but at least a pedestrian-friendly site would be a step in the right direction.

Convincing the powers-that-be won’t be easy. The 1994 closing of Alamo East, directly in front of the church, only took place after American Indians complained that the street ran over some of their burial grounds. “Closing the remaining streets is going to take a lot of things, including public pressure coming from the constituents, coming from citizens of San Antonio and the visitors,” says Foreman. “Because people forget who’s really paying the bills there. It’s not the locals. It’s the people who come to see the Alamo.”

Money Talks

Where do we go from here?

Back to the streets of San Antonio on that chilly afternoon with a hint of rain in the air. Winders and I are headed back toward the Alamo after our walking tour of the area. We’re both silent, thinking about a heritage that’s tantalizingly close, yet a meaning that’s lost on most people.

“I’m afraid we’re in danger of losing our history,” Winders suddenly says. “Not just the buildings. We’re not doing a good job of telling the stories and letting people know what happened and why it’s important.”

As he says that, we come into view of the classic front of the Alamo church, a reminder of a glorious past and an uncertain future. I know what Bruce is thinking, because I’m thinking the same thing: something must be done. Soon.