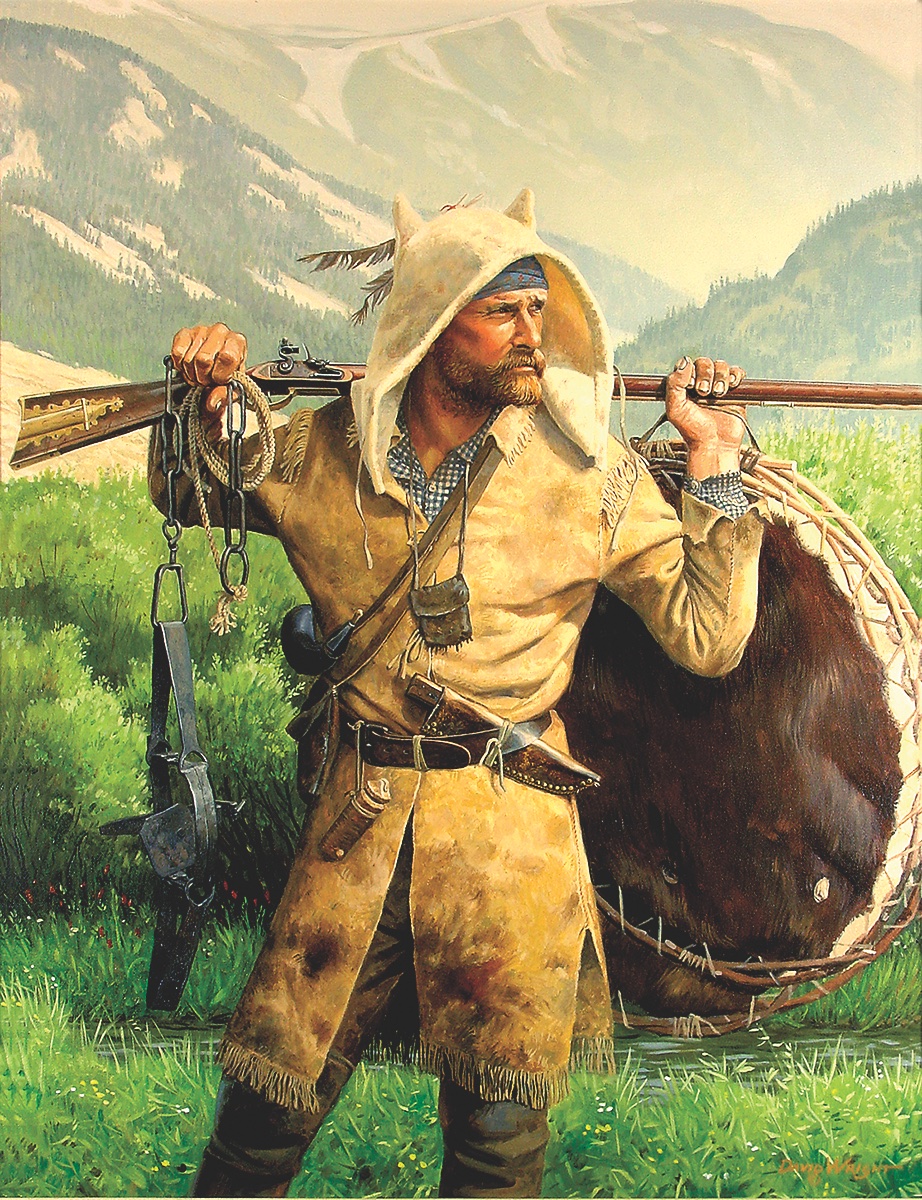

Casein on board • 20” x 30” • 1979

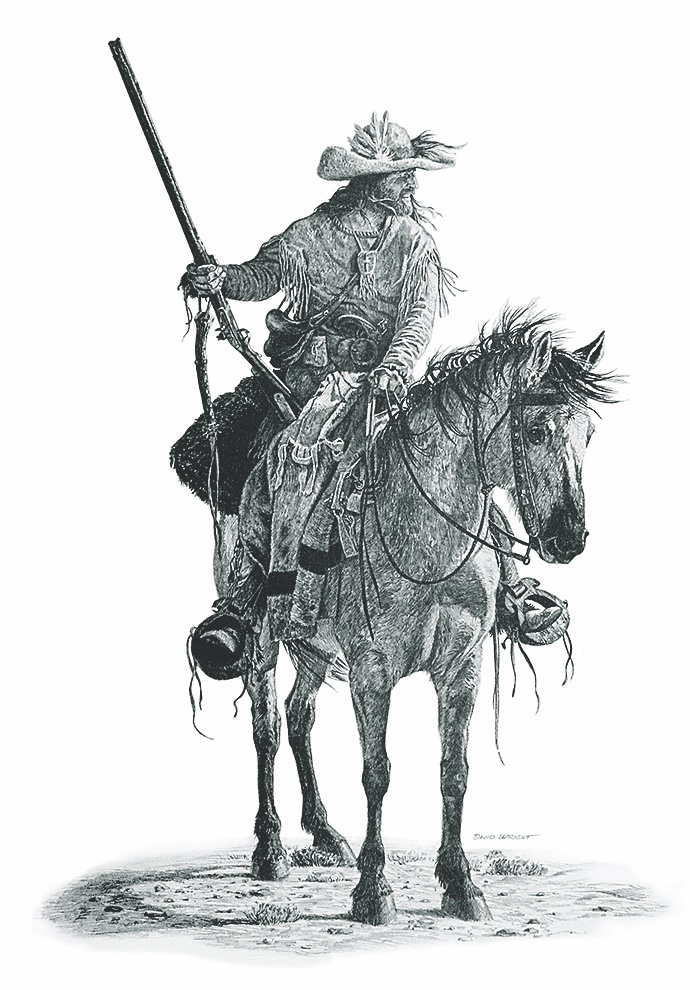

All artwork by David Wright

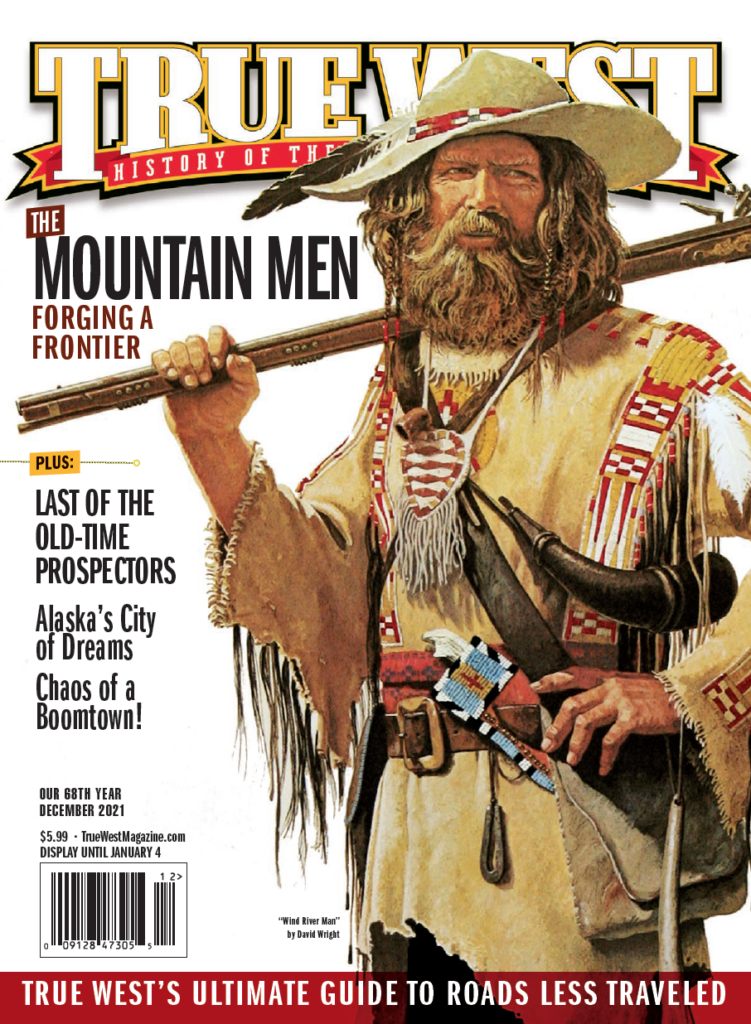

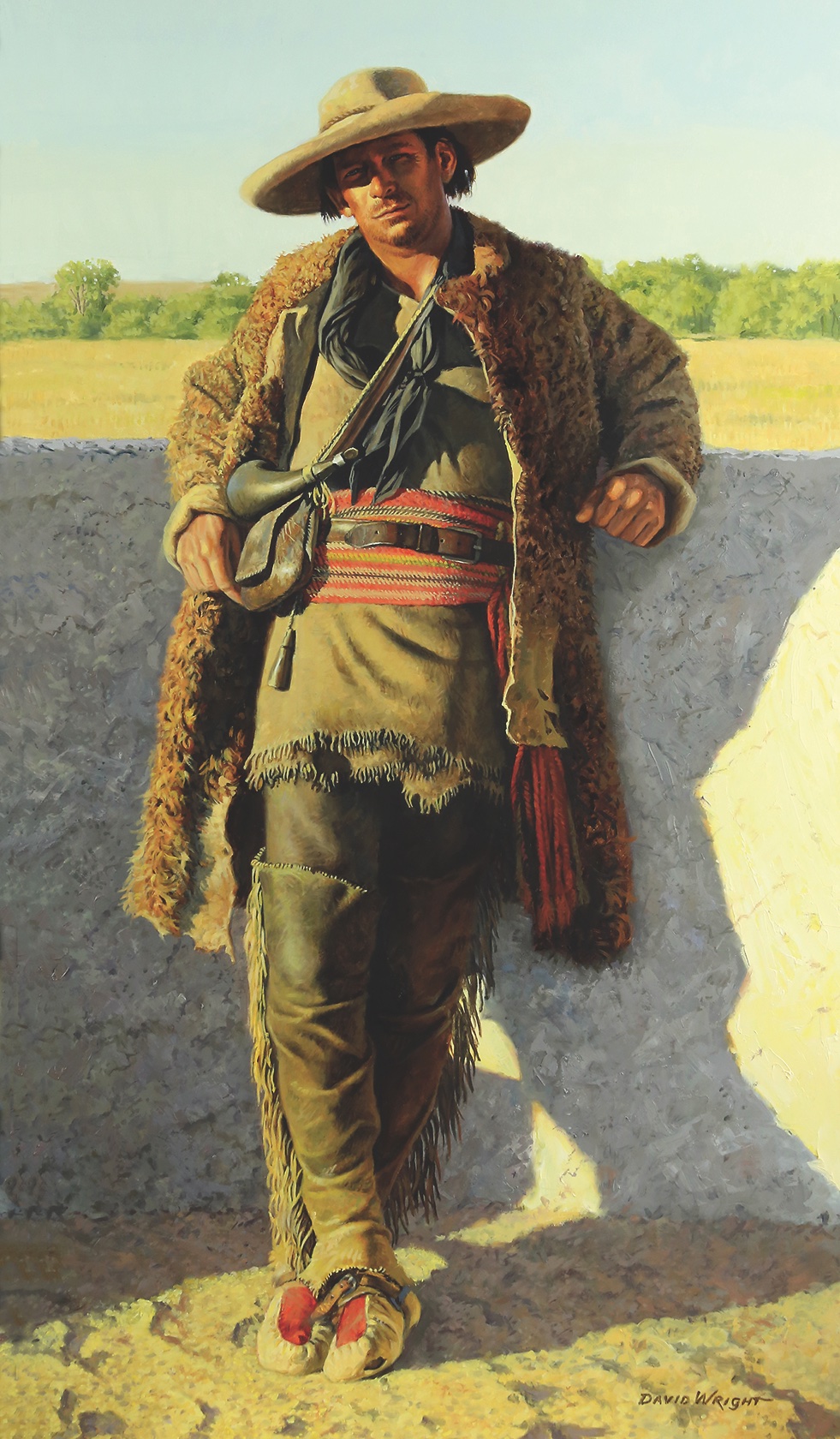

Validity, integrity and authenticity remain the watchwords of David Wright’s heroic renderings of the frontier. Born in 1942 in the hills of Rosine, Kentucky, the artist has built a storied career by blending on canvas his love of art, the outdoors and our nation’s fur-trade past. “I am fascinated with frontiersmen, the long hunters in the East and mountain men of the Far West,” he notes. “And I’ve always admired the lifeways and creative art of American Indians.”

Historians and frontier aficionados praise Wright’s work, while his artistic peers and reenactors study it for glimpses into an era when cameras did not exist. Critical to his muse is his rigorous pursuit of living history. “Utilizing the firearms and tools of another time gives me an edge in seeing what the lives of our frontier forebears were like. I know what it’s like to build a cabin, split rails, hunt with a flintlock and be freezing cold in 18th-century clothing. I know how wool feels in a snowstorm and how leather clings to your body when it’s wet.”

Acrylic on board • 10” x 16” • 1991

Wright’s quest for accuracy has taken him from Henry’s Fork on horseback dressed in brain-tanned buckskin and armed as Jim Bridger to Canada’s Alneau Peninsula by birch-bark canoe to hunt moose with the trappings of a Leatherstocking. His art, then, is best seen as an extension of the same linear flow, 150 years later, as that of Alfred Jacob Miller, George Catlin, Karl Bodmer and Frederic Remington.

The first three painters had a big advantage: their subject matter was in front of them. Wright has to recreate, in an informed way, what they saw but leave his own stamp on his art. Long cherished myths—like the Winchester `73 “won the West,” every mountain man sported a ZZ Top beard and toted a Hawken, and that Dan’l Boone wore a `coonskin cap—can be hard to sift through, but his studied insights give him flexibility in interpretation. Because his standards are so high in a medium so exacting, David Wright helps us see America’s past far better.

Casein on panel • 28” x 40” • 1984

The newest release by Western Writers of America Spur Award-winner and popular history writer Ted Franklin Belue is Finding Daniel Boone: His Last Days in Missouri & the Strange Fate of His Remains. He served as consultant for the INSP Network’s forthcoming frontier series, Wild Americans.

“I feel that it is the historical artist’s obligation to present and future generations to paint the subject with as much historical accuracy as possible.” –David Wright

Oil on panel • 14” x 20” • 2020

Oil on panel • 16” x 30” • 2020

Oil on panel • 24” x 30”• 2004

Pencil on board • 16” x 20” • 1981

Oil on panel • 11” x 14” • 2019

Oil on panel • 26” x 33” • 2013

Pencil on board • 12” x 12” • 1988

Casein on panel • 20” x 30” • 1980

Oil on panel • 36”x 48” • 2008

Oil on panel • 16” x 20” • 2006

Stereotypes: True or False?

Mountain Men…

…toted a Hawken like Jeremiah Johnson: Mostly false. Jim Bridger, Kit Carson and Mariano Medina used Hawken rifles late in life. Aside from a few strays, most Hawkens reached the Far West in the 1840s, just as the fur trade ended. A .56 caliber Hawken is attributed to John “Liver Eating” Johnston (the real “Jeremiah,” who prowled the Plains from 1862 to 1900). He also owned a hybrid sporting carbine fitted with a Spencer seven-shot magazine on a Hawken barrel—hardly a typical mountain man firearm.

…could not read: False.

Most could, actually. Many trappers wrote letters, kept diaries and journals. Fewer than 13 percent of them were illiterate.

...sported Santa whiskers: Mostly false. Frederick Ruxton, the day’s chronicler, described their appearance as being “clean-shaven, after the fashion of the mountain men,” though a few goatees appeared in the day’s art, notably that of Alfred Jacob Miller’s. Most men shaved to cut down on dirt and lice and stay on good terms with Indians; hirsute “Dog Faces” were not welcome in tribal societies. But since we do not have any artwork from deep in the woods, they may have let their beards grow before shaving, as David Wright’s Wind River Man illustrates on the cover and page 26. Come rendezvous, yes, clean up, shave, wash off months of beaver castor and other crud. Trappers did have notoriously bad hygiene, a big turnoff to Native women who bathed daily. Little wonder soap, along with razors, was a popular rendezvous trade item. Waugh!

…were antisocial cranks: False, except for Bill Williams, an eccentric but superior free-trapper and guide rubbed out by the Utes. Most were low-wage “company men” in their twenties operating in paramilitary fur brigades traversing a wild land that offered many ways to die.

…said Waugh! and referred to themselves as “this child”: Some certainly did, say authors Lewis Garrard and Frederick Ruxton, who rode with them and wrote books about them. Whether they all used such slang is doubtful; these cocks-of-the-walk were a multicultural, multihued lot and a famously boneheaded one.

…swindled Indians by getting them drunk to swap peltry for cheap gewgaws: False. Indians were conscientious consumers. Savvy traders met their demands by trading high-dollar wares for lush furs.

…craved buffalo tongues, hump meat, intestines (“boudins”) and beaver tails: Yep. Such delicacies were huge sources of the energy-producing fat mountain man

diets lacked.

—Ted Franklin Belue

Casein on board • 26” x 33” • 1981

Oil on panel • 20” x 24” • 2021