A trip tracking the Texas author across the Lone Star State is sure to create memorable stories.

The frontier town of Mobeetie was taking on some of the appearances of civilization, although not all the realities of it.”

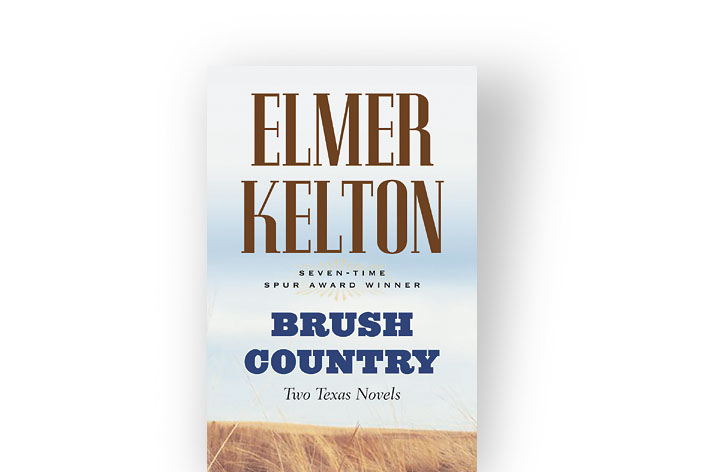

That’s the first description of a Texas town in any novel by Elmer Kelton (1926-2009). The West Texas native had written short fiction for several magazines in the 1950s, but Hot Iron, published in 1956, was his first novel. “That crowded and distinguished company of Western story-tellers must make room for a newcomer,” the Springfield, Missouri News and Leader wrote. “This is that ‘different’ Western you’ve been waiting for.”

The 30-year-old was just getting started telling those different kinds of Westerns.

Buffalo Wagons, published a year later, won him his first Spur Award from Western Writers of America. Six Spurs followed, plus four Western Heritage Wrangler Awards, including one for The Art of Howard Terpning for Outstanding Art Book, the Owen Wister Award for lifetime contributions to Western literature, induction into the Western Writers Hall of Fame and praise as the greatest Western novelist of all time.

“None of his works fit exactly into the stereotypical Western genre,” The New York Times observed in 1986.

Kelton usually wrote under his own name, but used pseudonyms, Alex Hawk, Tom Early and Lee McElroy, and while some novels strayed outside of Texas, he set most in the Texas he knew best.

Panhandle Tales

Mobeetie (Mobeetie Jail Museum) was established in 1874 as a buffalo hunters camp, Hidetown, and grew with the establishment of Fort Elliott and the Jones and Plummer Trail for those buffalo hunters. In Hot Iron, Espy Norwood is sent to manage a Panhandle ranch and brings his 11-year-old son into a range war.

Kelton returned to the Panhandle with Buffalo Wagons, about the slaughter of buffalo herds by white hunters in the 1870s, and Kelton revisited hide hunters in the Spur-winning Slaughter, 1992, which fictionalizes the 1874 attack on the Adobe Walls trading post northeast of Stinnett in Hutchinson County. “Though crude,” Kelton wrote in Slaughter, “the little village had a certain straight-line symmetry. It was not a place that would impress a man who had spent most of his life in and around the mannered villages of England. …Give it a hundred years and it might come up to civilized standards.”

Kelton created most of his towns, or rather transformed towns that he knew well as a journalist for the San Angelo Standard-Times and livestock periodicals, giving them names like Catclaw, Dry Fork, Piedras and Rio Seco. You won’t find Caprock, his 1920s oil boomtown depicted in Honor at Daybreak (1991) on any Texas map, but it existed in Crane, where Kelton was born. “My father’s family were ranch people,” Kelton wrote, “while my mother’s were tied to the oilfields.” The Panhandle town of Borger (Hutchinson County Museum) or West Texas’s Midland (Permian Basin Petroleum Museum) could also have passed for Caprock, “our little Sodom in the Sandhills.”

Another Spur winner, The Day the Cowboys Quit, 1971, was based on an 1883 cowboy strike around Tascosa, near Amarillo and home to Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch for at-risk children ages 5 to 18. Talk about a different Western. “Nobody got shot to death in the story,” Kelton told the New York Times. “There wasn’t any big gunfight. One man died in the whole book, and he died offstage.”

Kelton enjoyed writing about the Panhandle, from Amarillo (American Quarter Horse Hall of Fame) to Canyon (Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum). Palo Duro Canyon State Park served as the inspiration for Kelton’s The Far Canyon, 1994, a sequel to Slaughter. And Kelton was a top draw at the annual Cowboy Symposium in Lubbock (National Ranching Heritage Center). But he covered most of Texas.

Expanding the Western

The 1970s saw an increased depth in Kelton’s prose—the Black cowboy’s fight against prejudice in Wagontongue, 1971; the 1950s drought in The Time It Never Rained, 1973; a fictionalized version of the Gregorio Cortez legend in Manhunters, 1974; and the seriocomic story of a turn-of-the-century cowboy in The Good Old Boys, 1978, adapted as a made-for-TV movie for TNT in 1995.

When he wrote about actual events, Kelton had a gift of making a point without exaggeration or gore. Massacre at Goliad, 1965, told of a young Texan’s brush with death during the Texas Revolution, when Mexican soldiers shot to death prisoners at Goliad (Presidio Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahía).

“Jimson gave voice to the sudden horrible realization that swept over us all. ‘My God, boys, they’re goin’ to kill us.’

“I heard someone cry out. Men began to pray. One man dropped to his knees, his head bowed. Someone shouted, ‘Rush them, boys! It’s our only chance!’”

Or the recollection by Frank Claymore, a thinly disguised Charles Goodnight, of the massacre of Kickapoo Indians in 1865 at Dove Creek near present-day Mertzon in Stand Proud, 1984.

“He saw an older man, an overseer of sorts, waving a white cloth, shouting something that was lost in the rush and the wind. The man went down, his horse bolting away. The white cloth caught on a bush and continued to flutter its lost message in silence.”

At Home in West Texas

Kelton specialized in West Texas, “never an easy, benevolent land,” he wrote in The Good Old Boys. “For whatever it yielded up, it exacted a price.”

Most of his fiction was set around San Angelo, where he lived most of his life, and where he is buried at Lawnhaven Memorial Gardens. “It’s a handy town,” a soldier says in The Wolf and the Buffalo, only to be corrected: “It’s more like a boil on a soldier’s butt.”

The buffalo soldiers from The Wolf and the Buffalo were stationed here, and visitors can learn their true stories at Fort Concho National Historic Landmark. It’s not hard to imagine The Good Old Boys’ Hewey Calloway eating at Miss Hattie’s Restaurant & Cathouse Lounge or getting into trouble at Miss Hattie’s Bordello Museum.

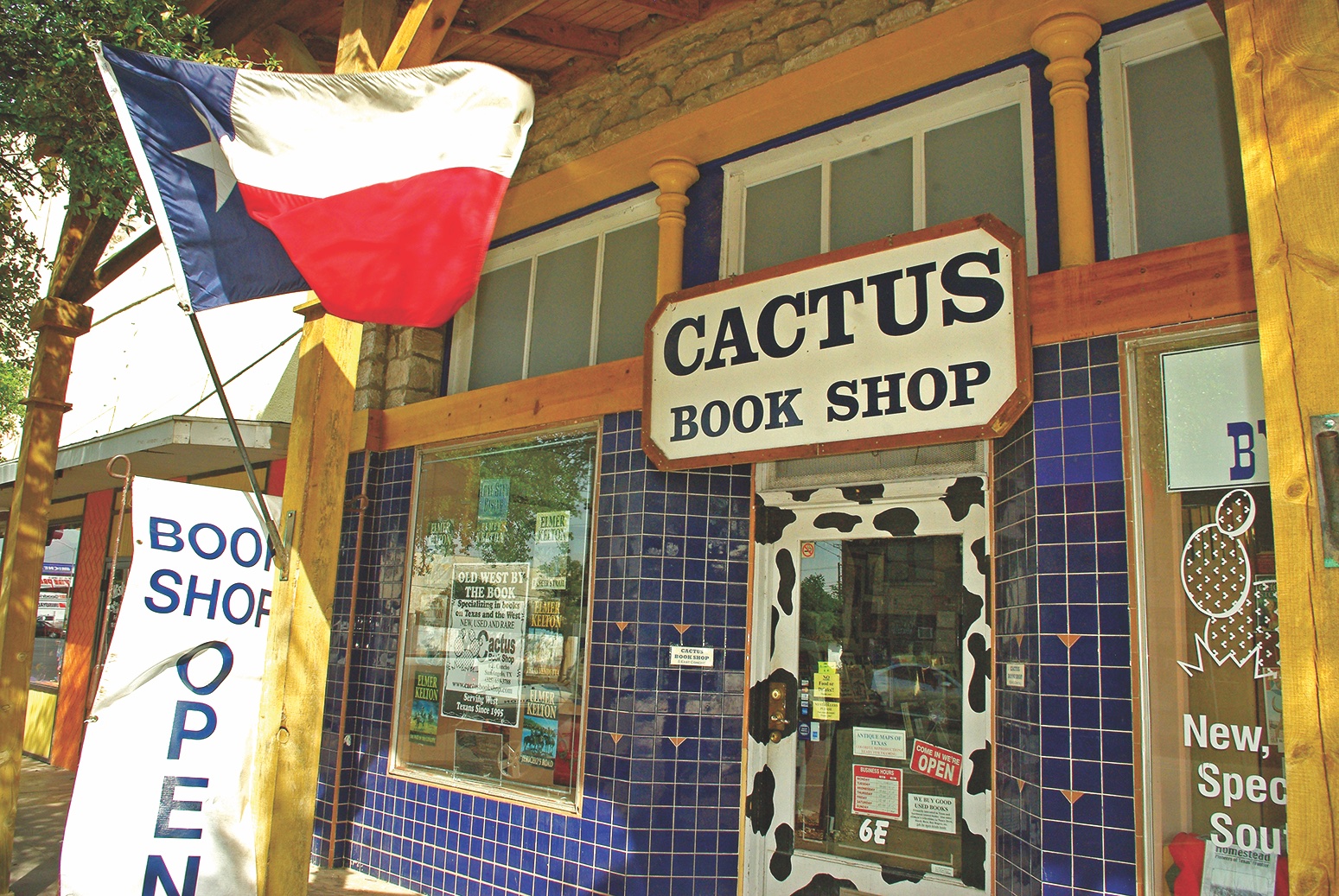

Kelton’s presence remains large in San Angelo, including Raul Ruiz’s sculpture at the central library, Stylle Read’s downtown mural and Kelton’s books for sale at Cactus Book Shop.

Kelton’s funeral at San Angelo’s First United Methodist Church concluded with the playing of “Happy Trails.” “Very Western,” historian Paul Andrew Hutton told the New York Times, “all the way.”

A Wide Spot in the Road

FORT GRIFFIN STATE HISTORIC SITE

Since 1948, Fort Griffin State Historic Site has been the primary home to what the state Legislature recognized as the “Official State of Texas Longhorn Herd” in 1969. Official longhorns also graze at San Angelo, Copper Breaks, Abilene and Palo Duro Canyon state parks. Part of Elmer Kelton’s 2002 novel Ranger’s Trail was set around Fort Griffin, and the region the fort protected from 1867-81 was territory Kelton often covered in his prose. The parasite town that grew up around the military post was a mecca for buffalo hunters. Historical figures, including Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson, John Selman, Kate Elder and Lottie Deno, reportedly hung out there. Ruins of the fort can be seen today, along with Settling the Plains: The Story of Fort Griffin, an informative documentary at the visitors’ center. More than 30 campsites are available, or lodging can be found in nearby Albany. THC.Texas.gov

Good Eats and Sleeps

Good Grub: Coyote Bluff Café, Amarillo;

The Funky Door Bistro & Wine Room, Lubbock; The Taylor County Taphouse, Abilene; Roxie’s Diner, San Angelo

Good Lodging: Historic Starlight Canyon Bed & Breakfast, Amarillo; Hotel Turkey, Turkey; Antlers Inn, Goliad; Old Central Firehouse Bed & Brew, San Angelo