Jim Bridger, once a teenaged mountain man, became the most dependable and renowned trailblazer of the vast lands of the American West.

For more than a century, some historians have marked a distinct period of exploration dating from the expedition of Lewis and Clark in 1804–06 to the establishment of Fort Bridger on the Oregon Trail in 1843. Jim Bridger played a significant role in that period and in the next as well.

Bridger was a mountain man, “the proudest of all the titles worn by the Americans who lived their lives out beyond the settlements,” wrote Bernard de Voto in The Year of Decision, 1846. And he was one of the best of the mountain men, with courage and skill, knowledge and determination. He lived a life wild and free, and he embodied an American ideal, as Daniel Boone had a generation earlier. Bridger had not set out to be a hero. What had mattered to him, as it happened, mattered to the nation: exploring the Rockies, discovering the Great Salt Lake, opening the routes to Oregon and California, and forging alliances with the Shoshones, Salish, Nez Percé and Crows.

A Company Man

Under Andrew Henry and William Ashley’s direction, Bridger and his fellow trappers had been active participants in revolutionizing the fur trade. With free trappers, overland routes and the annual rendezvous, there was no need for established forts. The men were free to hunt the mountains year-round, and by living in lodges each winter, they were able to set traps each fall and spring, the prime trapping seasons. They could be resupplied each summer and only paid when they brought in pelts.

The first Rocky Mountain rendezvous in July 1825 marked the beginning of a new way to supply American trappers and collect their hauls. Bridger and the others would remain full-time hunters, spending the whole year in the mountains instead of taking time to travel to and from St. Louis each spring and fall. A supply caravan would come west each spring laden with goods and return to St. Louis with beaver skins.

Rendezvous was not just a time to swap goods. For Bridger it was a connection to the life he had left behind some twelve hundred miles to the east. It was also a time for him to learn what had happened to fellow trappers who had been hunting other regions and what had transpired with the leadership of the company during the past year.

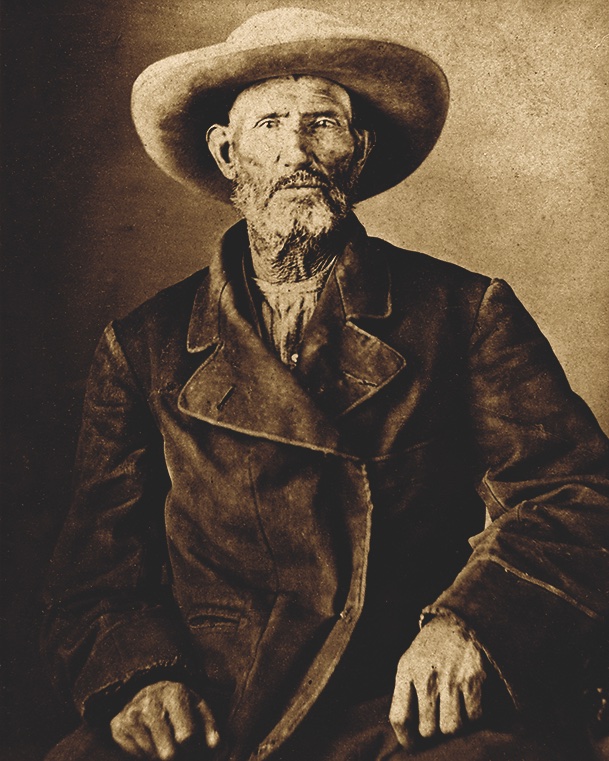

Courtesy Kansas State Historical Society

Pilot for the Brigades

Following the 1826 rendezvous, Bridger became one of the leaders in William Sublette’s foray into the dangerous but beaver-rich lands of the Blackfeet. Over the past two years Bridger had proven his reliability and self-reliance through his solo exploration of Bear River to the Great Salt Lake, his solo shooting of the rapids at Bad Pass and his leadership with Fitzpatrick in retrieving the stolen horses from the Bannocks. Though Bridger was only 22 years old, he had four years’ experience and was now one of the “spies” sent several miles ahead to scout the terrain and report any danger or possibility of attack. He would then signal his discoveries or report directly to the brigade leader.

The Sublette party trapped their way to Pierre’s Hole (in present-day eastern Idaho), which offered stunning views of the Teton Range and its three prominent peaks. This became one of Bridger’s favorite places. These peaks had been called the Pinnacles, the Pilot Knobs, the Three Paps and the Three Brothers; the Shoshones called them Hoary Headed Fathers. But the romantic name that prevailed was the French “Trois Tetons” meaning “three breasts.” (The name had earlier been attached to a formation on the Snake River plain that came to be called the Three Buttes.

The trappers crossed the mountains west to east, either through Conant Pass or Teton Pass, and came to the stunning valley on the eastern slope of the Tetons, soon to be known as Jackson’s Hole, after David Jackson. But the beauty of the setting was countered by the cunning of the Blackfeet who harried the American interlopers. From that high valley the brigade trapped north along the course of the Lewis River, a tributary of the Snake River. The land kept rising, and soon they stood six hundred feet above the river. The brigade eventually came across a huge alpine lake, refreshingly cool and remarkably blue. They called it Sublette’s Lake; it would later be known as Yellowstone Lake.

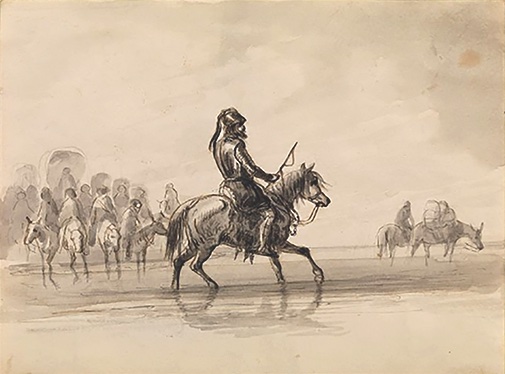

In the 1820s and 1830s, this band of adventurers, which included Bridger, became the most significant group of explorers ever assembled in North American history. They called themselves mountaineers, and Washington Irving described them: “A totally different class has now sprung up, ‘the Mountaineers,’ the traders and trappers that scale the vast mountain chains, and…move from place to place on horseback…heedless of hardship; daring of danger; prodigal of the present, and thoughtless of the future. There is, perhaps, no class of men on the face of the earth who lead a life of more continued exertion, peril, and excitement.”

Wintering on the Wind River

In the fall of 1828, Bridger piloted Robert Campbell’s 12-man brigade to Crow country. They hunted along the Powder, Tongue and Bighorn rivers and then wintered with the Crows on Wind River under Long Hair, an 80-year-old chief whose hair measured just under ten feet long. His people had to carry it for him as he walked. Bridger likely guided Campbell’s brigade to Crow country again in 1829. In January, Beckwourth decided to leave the brigade and live with the Crows, but he embellished his departure with an implausible tale of Bridger reporting the “painful news” of his death and the trappers mourning his loss.

Unless Otherwised Noted All Alfred Jacob Miller Art (c. 1858-1860) Courtesy The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland

The 1829 rendezvous was held on the Popo Agie near the Wind River, and Campbell traded for 4,076 pounds of beaver pelts that he hauled back to the States. A second rendezvous of sorts happened that year at Pierre’s Hole, where the mountain men were finally reunited with Jedediah Smith. He told them how the Mohaves had killed 10 of his men in the summer of 1827 as they tried to cross the Colorado River in two shifts, and how the Kelawatset Indians had killed 15 of his party on the Umpqua River along the Oregon coast in 1828. Bridger may have piloted Jedediah Smith and William Sublette in fall 1829 as they traveled the Snake River, the Missouri River headwaters and the Yellowstone River. On their way to winter camp in 1829 they crossed the mountains from the Yellowstone to the Bighorn, where the snow was so deep they had to break a path for their horses and mules. The animals still sank to their haunches in the snowdrifts. They lost a hundred animals from starvation and from being trapped in the snow.

“Trapping Beaver” by Alfred Jacob Miller

The Mountaineer

It was obvious to Bridger and the rest of the men on Wind River that they could not find enough forage for their horses and would soon be counting the animals’ ribs. To reach a valley where their horses could survive, they would have to cross the mountains. On New Year’s Day 1830 they began their journey, trudging through deep snow by day and huddling around fires by night. By mid-January they reached Powder River, the paradise they had hoped for.

Buffalo roamed thick in the cottonwoods and grazed into camp, a walking feast coming right up to the cook fires. They had to post double guards to keep the buffalo from trampling their lodges. Bridger and others regularly gathered cottonwood bark for their horses, carrying branches to camp, making draw knives to strip the bark, and bringing the shavings to the horses, which crowded each other to get to the nutritious peelings.

They shattered the solitude of winter with the echo of axes, the braying of the mules and the whoop of the mountaineers. They told epic tales of adventure and filled the night with stories, some of them true. Smoke floated in a haze above their fires as they tried to retell from memory the storylines of their favorite books. Joe Meek, a Virginian who had come to the mountains the previous summer, learned to read while sitting at the campfire. He labored over “an old copy of Shakespeare, which, with a bible, was carried about with the property of the camp.”

The ice broke in April, and the trappers set out to cross the mountains with Smith as their captain and Bridger as pilot. Bridger led them to the Tongue River and then the Bighorn. A heavy snowfall made travel difficult, and Bovey’s Fork of the Bighorn River quickly rose from the runoff. They led their animals into the swift current, but it proved too strong for them and swept many away. The animals gasped for air and screamed in panic, and the mountaineers struggled to not be pulled away with them. Thirty horses drowned and three hundred traps went down with them, a significant loss to the trapping brigade.

Bridger led them west over a low range through Pryor’s Gap to Clark’s Fork, the Rosebud and finally the Yellowstone River, which was still high in its banks. They made bullboats by stretching buffalo hides over willow frames and floated themselves and their gear across. Bridger then took them to the Musselshell and the Judith rivers, where Henry’s men had trapped their first season in the mountains in 1822. As always, the Blackfeet were a constant presence, harassing the trappers and stealing traps and horses.

When they reached the Bighorn, a party of men under Samuel Tullock tried to excavate a cache of furs. The overhead soil caved in on Meek and a Frenchman named Glaud Ponto, who often spent his money on riotous behavior. Their companions dug the trappers out of the caved-in cache, only to find Meek seriously injured and poor Glaud Ponto dead. He was “rolled in a blanket and pitched into the river.” This was the same Ponto who two years earlier had returned to St. Louis from the 1828 rendezvous to find that his brother had died. He told his companions, “I am mighty glad my brudder died and I got his fine clothes.”

Despite the deadly accident, Tullock got his pelts and joined the other trappers as they headed for the 1830 rendezvous. Bridger looked forward to the gathering but had no idea of the good fortune that lay in his future.

Knight of the Rockies

Bridger is often viewed as his era’s greatest American frontier scout. His knowledge of the West was uncanny, and his frontier survival skills were unparalleled. He could read the land at a moment’s glance and recall thousands of miles of past trails in an encyclopedic recital. His contributions to Western exploration and history are enormous, though the details are often forgotten today.

He discovered Great Salt Lake when he was 20 and ran the Bad Pass rapids at 21. He led Rocky Mountain fur trappers, including Kit Carson, throughout the West, and interpreted and mapped for the great Horse Creek Treaty of 1851. He built Fort Bridger on the Oregon and California trails and helped chart Bridger Pass and the Overland route that became the preferred route across the Rockies.

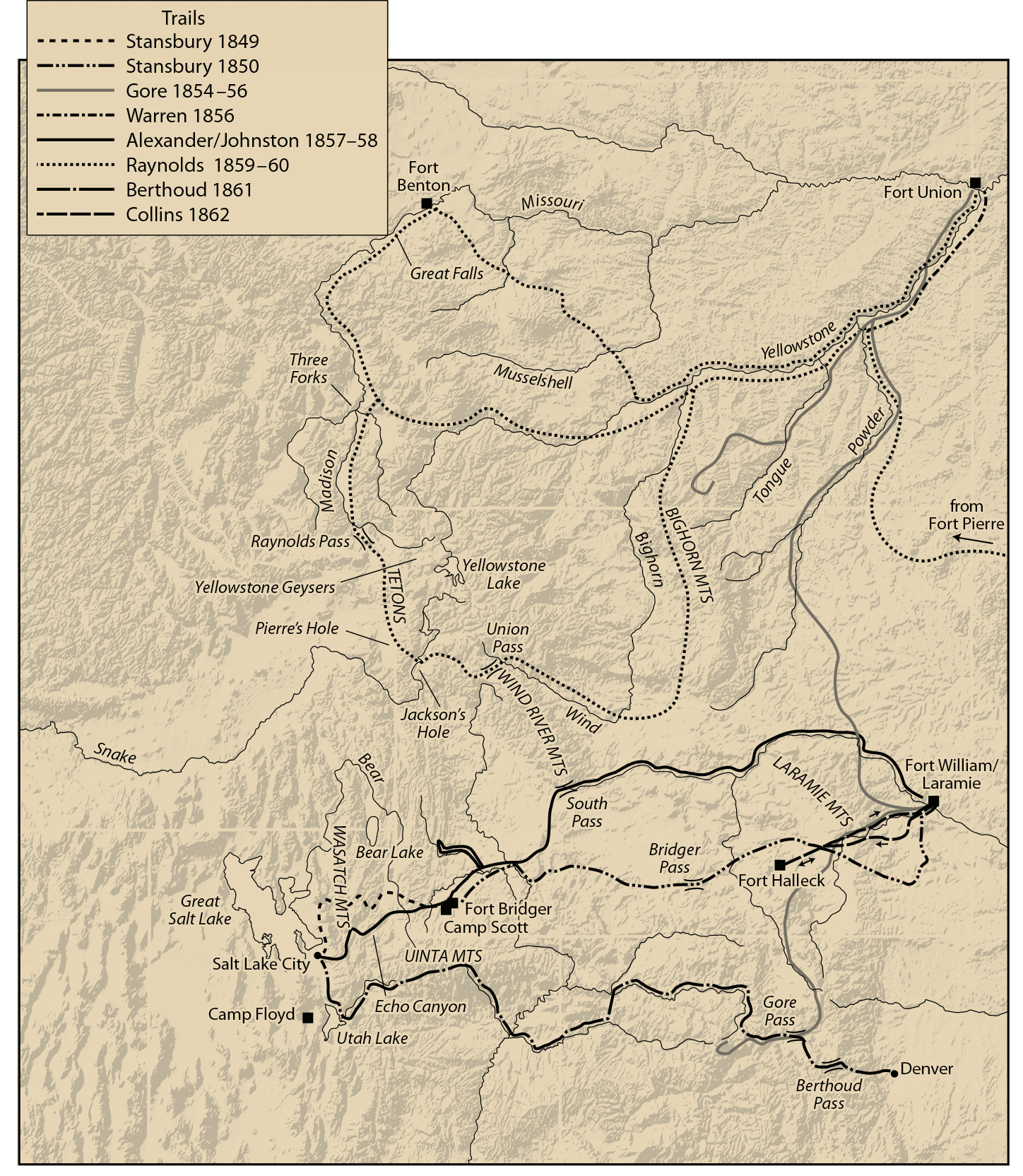

Bridger guided more trappers, emigrants, miners, engineers, scientists and soldiers than any scout in American history. He was chief scout for noted cartographers and scientists Stansbury, Warren, Hayden and Raynolds, and he guided major military expeditions for Johnston, Collins, Connor and Carrington.

Bear River Canyon and Bad Pass.

“The Devil’s Gate” by Alfred Jacob Miller

Equally significant, Bridger was a friend and ally to the Shoshone, Crow, Flathead, Nez Percé and Ute Indians. He was widely respected by the Cheyennes, Sioux, Arapahos and other indigenous peoples and could invariably treat with them to avoid conflict. He blazed the Bridger Trail and advocated for its use to try to prevent the bloody war with the Sioux, Cheyennes and Arapahos that lasted from 1865 to 1868. When the Army foolishly selected the Bozeman Trail instead, he tried to protect the lives of soldiers who built their forts in Indian lands.

Bridger went west at age 18 and lived among the Indians and the mountains. He had a sense of family when he traveled with the fur brigades. Then he married and had his own family with the Flathead woman, Cora; the Ute woman, Chipeta; and the Shoshone woman, Mary. When he had to leave Fort Bridger, his only permanent home in the West, he settled in Westport, Missouri, but he also lived on the road as a scout for more than a dozen expeditions. When he wasn’t guiding, he often found a bunk at forts Laramie, Phil Kearny and C. F. Smith.

All of Bridger’s life he searched for home. In that journey he found America and helped shape it.

“The Trapper’s Bride” by Alfred Jacob Miller

Map by Bill Nelson, Courtesy the University of Oklahoma Press

“James Bridger”, 01.1750. 1879, Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Editor’s Note:

In 1837, Scottish adventurer William Stewart hired artist Alfred Jacob Miller to paint the spectacular scenery, the mountaineers and the Indians of the Rocky Mountains. In 1858-60, Stewart paid Miller to produce paintings from his sketches, and they offer today some of the best first-person perspectives on the day-to-day lives of the mountain men in the West.

“Knight of the Rockies” is an excerpt from Jim Bridger: Trailblazer of the American West (University of Oklahoma Press, 2021). Jerry Enzler, a renowned Bridger expert, directed the National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium in Dubuque, Iowa, for 37 years.