The odds are good that a visitor to Nome, Alaska—landed as a cruise ship passenger or spectator of the Iditarod race finish—will pause before an antique roulette wheel enshrined at the Carrie M. McClain Memorial Museum. A label below the hairline-cracked, painted disc says it came from George Louis “Tex” Rickard’s saloon, the Northern, once located just up the street.

Luminaries from Wyatt Earp to Jack London, pulp fiction writer Rex Beach, and President Herbert Hoover supposedly touched this relic of frontier entrepreneurship. That has been hard to prove. A son of the couple who gave it to the museum remembers playing with it as a child in his parents’ attic. How it got there from the Northern and how it got to the Northern remain mysteries.

Rickard had befriended Jack London during the Klondike gold rush and opened the first Northern, in Dawson. A gambler to the hilt, he lost his share in it. Conceivably, the roulette wheel then traveled with Rickard from Dawson to Nome. He convinced his pal Wyatt, who briefly managed a canteen in Saint Michael, at the Yukon River mouth, to help him in mining Nome’s miners.

The starry-eyed visitor imagines the town’s rowdier, glory days. “For there’s never a law of God or man/Runs north of Fifty-three.” Jack London used Rudyard Kipling’s lines as an epigraph to a tale set in the city where no tree could be found for a lynching.

A Boomtown is Born

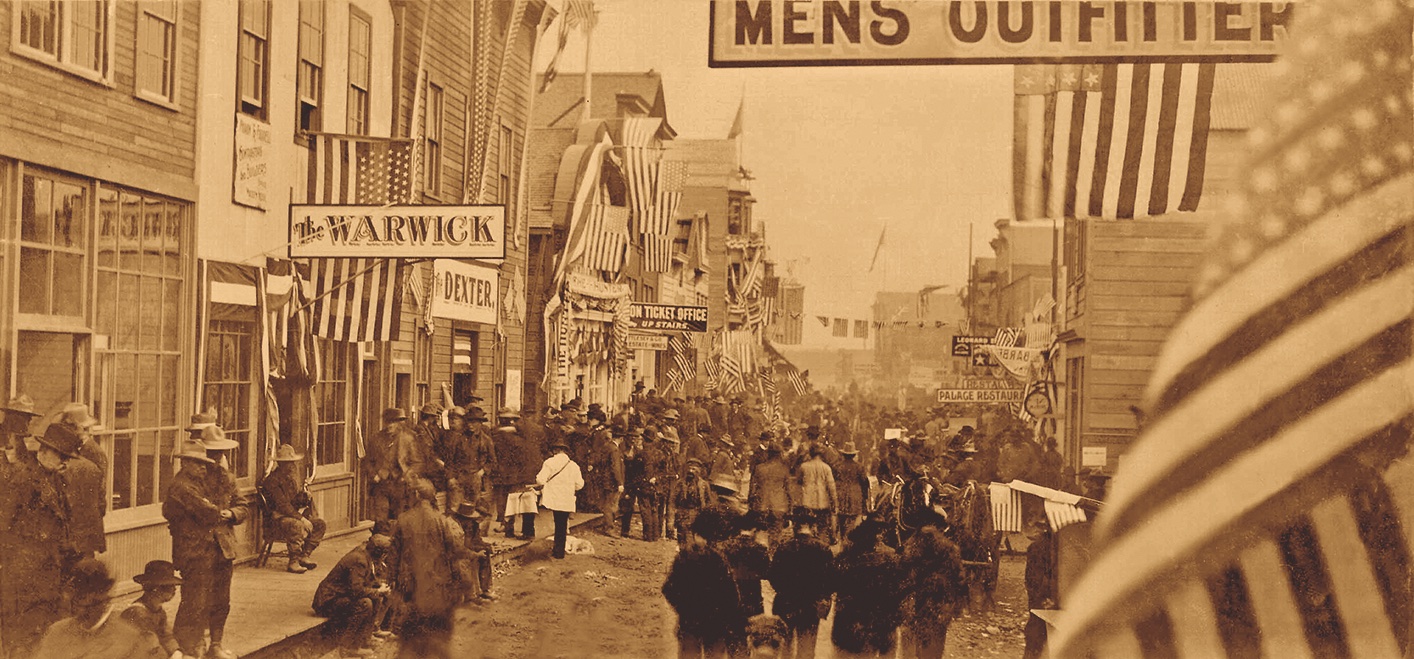

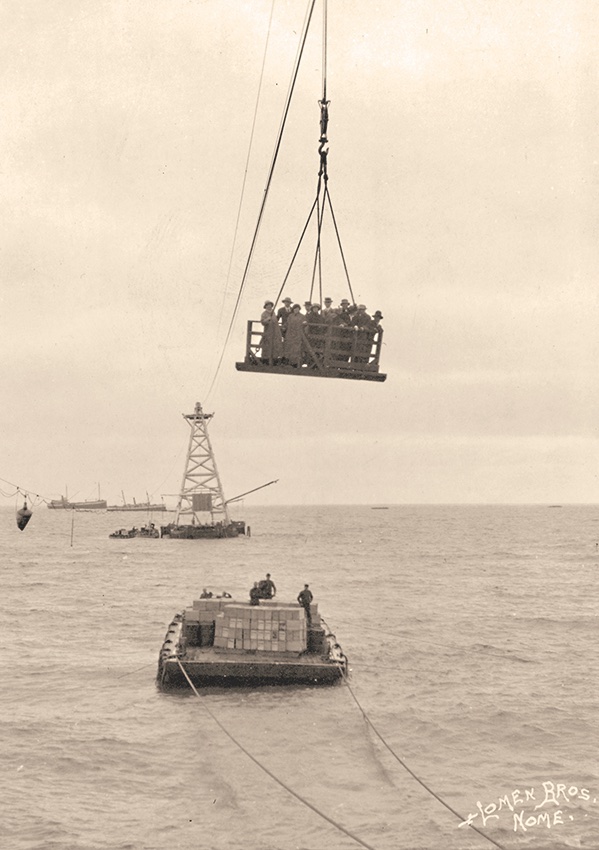

Nome, incorporated in 1901, became during the summer of 1900 the territory’s largest settlement and the world’s busiest seaport without a harbor. About 15,000 gold hunters alighted in June, weary of the Klondike, Seattle or San Francisco. More left Adelaide, Australia, on the steamer Inca two years later. Droves of mariners jumped ship to join the fray.

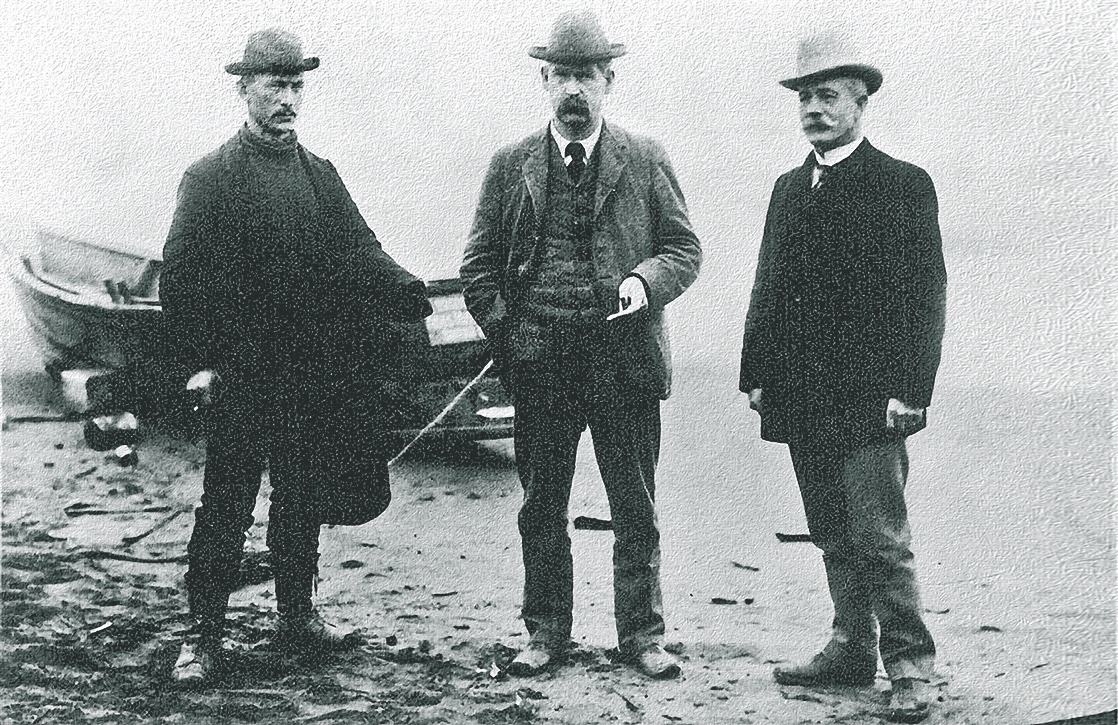

Nordmän woefully late for the Klondike in 1898 had unleashed all this wanton craving: the Swedish tailor Erik Lindblom leapfrogged north as a deckhand on a whaler; Jafet Lindeberg from Norway wrangled free passage pretending to be an expert herder; only John Byrnteson, the third of these “Three Lucky Swedes,” had wrested wealth from the ground professionally, mining iron and coal.

A limestone outcrop on a mountain above the creek where the trio struck paydirt lent the settlement its initial name: “Anvil City.” Within a year, Anvil Creek’s entire silver-gray schist bed got worked over at least once. A mapmaker’s scribbled Cape (Name?), misread, then may have morphed into the headland and town’s current designation.

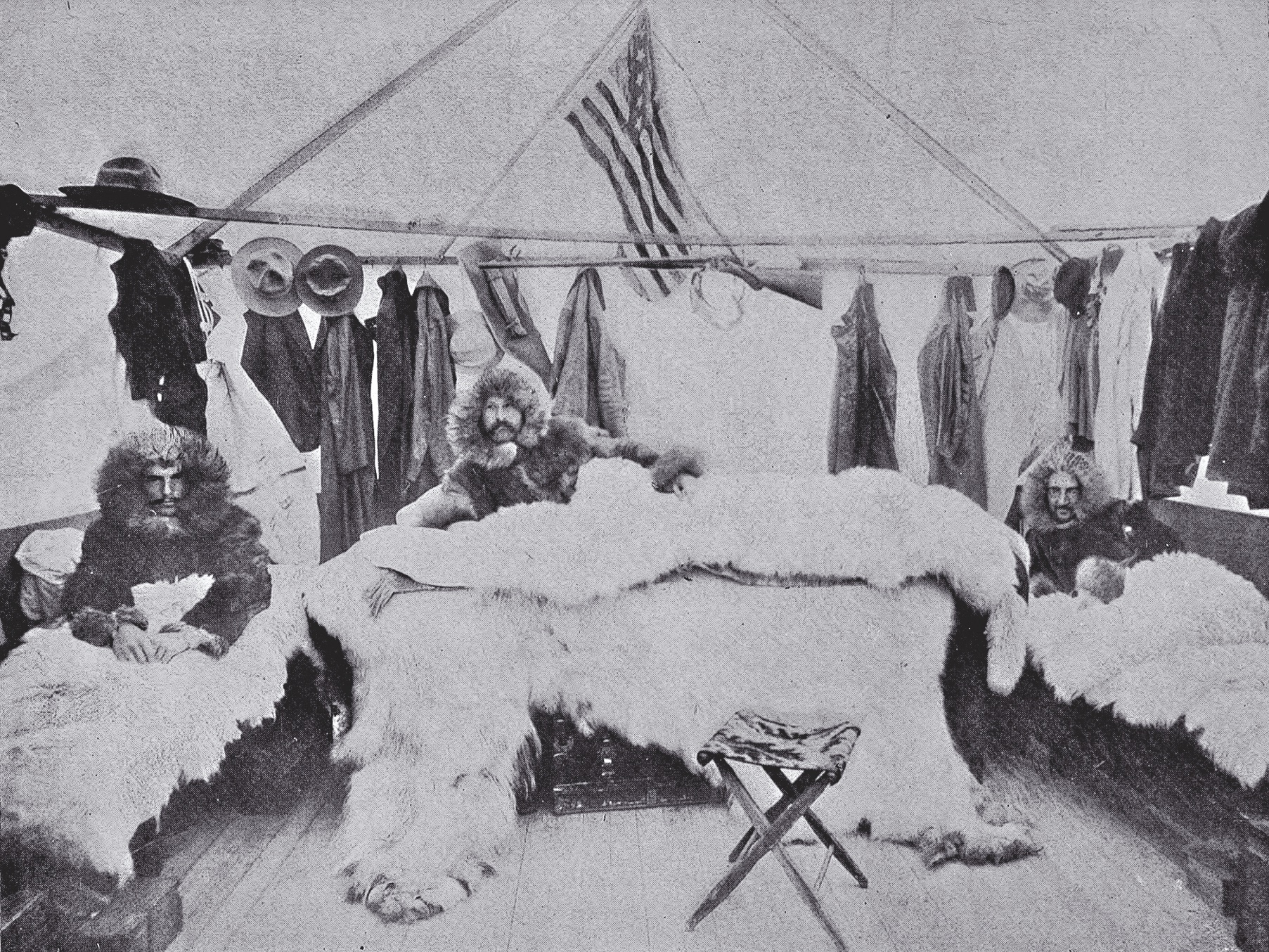

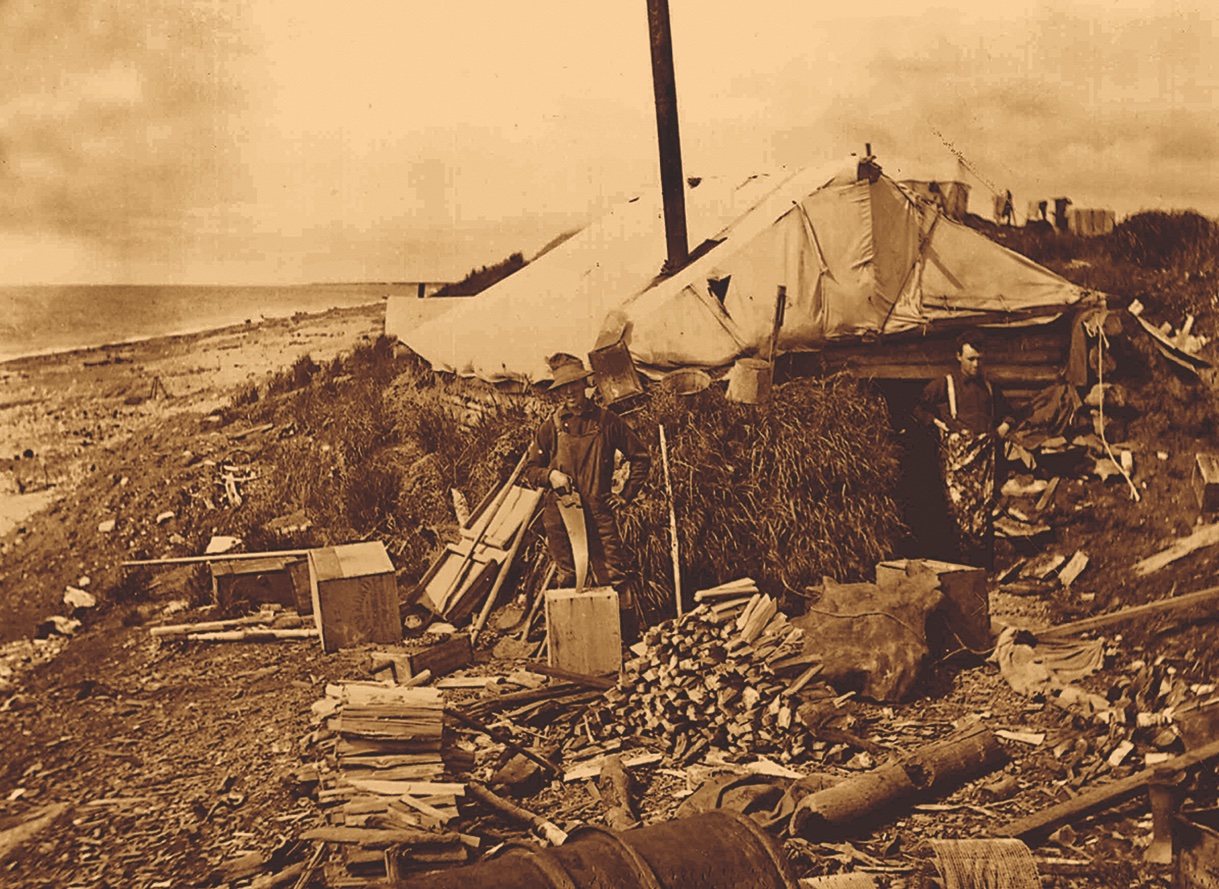

From the perspective of arrivals anchored in Norton Sound, the foreshore’s low ridges appeared littered with icebergs. Up close, those dissolved into a warren of canvas tents. Camps sprawled across 30 miles of coastline, from Cape Rodney to Cape Nome. Men piggybacked women to shore, queens vastly outnumbered in the Anglo anthill. Mountains of freight clogged the beach, a black-sand strip 60 feet wide: grain, hay, general merchandise, mining equipment and provisions, sewing machines… Luxuries heaped up there amid driftwood: pianos, fancy mirrors, and casks of brandy and bourbon, and eggs, selling for $15 a case. Longshoremen simply dumped freight next to the water’s edge. A team of huskies hauled a wheeled water barrel, mutts powering Bacchus’s chariot. Absent natural shelter or sanitation, mayhem reigned with tarps flapping, and dog packs marauding between fly-buzzed offal and broken boxes. The city eventually commissioned waterfront closets on pilings the tides flushed.

Greenhorns broiled in the sun or, shivering under blankets, hugged hostile ground. Some, not eating regularly, improvised huts with packing crates or boats flipped onto their sides. A Newcastle-on-the-Tyne coal miner died of typhoid in his beach abode, leaving behind a watch, compass, rifle and knife as his sole possessions. The chief of police pulled a letter from the miner’s pocket. Phema, a sweetheart in England, had begged her man not to go to Alaska but to come home.

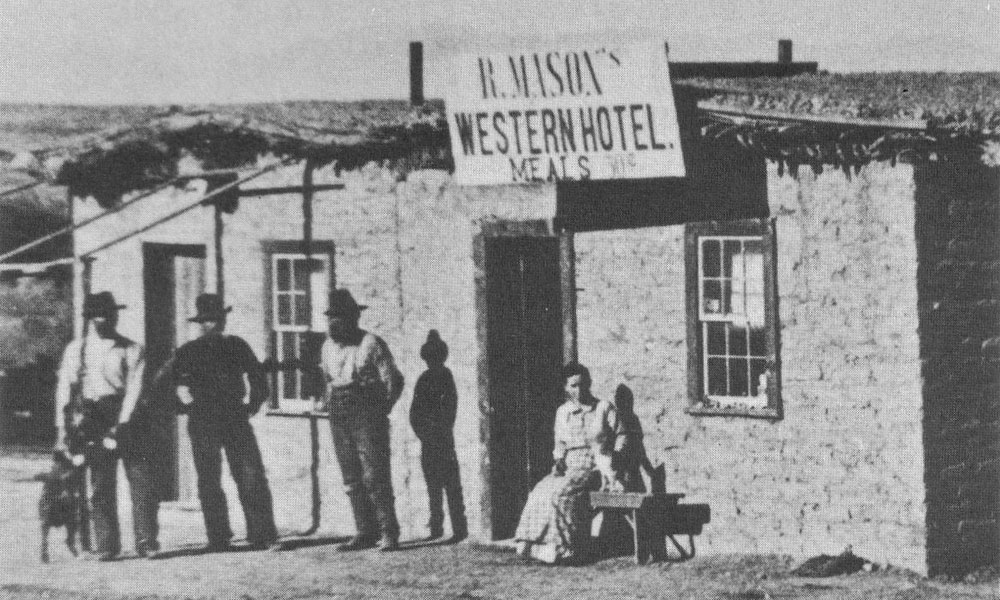

Lumber had to be freighted in, as the driftwood was of poor quality. An embalmer and undertaker announced his hope to put up a morgue as soon as supplies arrived. The City of Chicago became a hotel and beer garden, the Quickstep, reached via gangplank, a restaurant and hotel. A forerunner of Wild, Wild West Steampunk designed to ease into the shallows on barrel wheels to dredge the seafloor was so heavy it never moved. An even grander harebrained scheme proposed building a casino—theater, saloon, hotel and dance pavilions—a marine league from shore on ice to evade gambling laws. The town teemed with lawyers and laborers, hostlers and quacks, card sharks and clerks, madams, storekeepers, laundresses, land speculators and dance hall girls. Nome sprawled “all length and no breadth” two blocks wide and five miles long. Boardwalks covered Steadman Avenue only. Front Street, a dust bowl in the summer, here and there bottlenecked to 15 feet. In the fall, a “slough of despond,” it swallowed wagons up to their axles and mules to their bellies. For one fortune seeker, “It really was part of the beach.” Mobs roiled. Foghorns moaned. Saws ripped, surf and hammers pounded. Mongrels fought over scraps. Mules bawled in their traces. Nome was “a perfect Babel of noise.”

Arctic Babylon

The veteran prospector E. C. Trelawney-Ansell thought cheaper, easy access to Nome—merely stepping out of a lighter after they’d boarded a steamer on the West Coast—lured more shifty-eyed schemers than had the arduous Klondike:

“Nome was different, it was a place where the creeks and the town itself filled with thousands of cheechakos who had never known the hardship of the trail and few if any other hardships. Worse still, the camp and surrounding country was filled with gamblers, cutthroats and murderers of the worst kind.”

Nearly all the promising claims had been jumped at least twice by July 1899, and multiple claimants contested others. The Three Swedes were accused of being aliens and thus having staked the best grounds illegally. Two actually were naturalized citizens.

In November, a headless body washed ashore. A Cape York recorder suffered when his cabin and books burned; the fact that one miner had secured over 140 claims there could have been a clue. A Cripple River recorder refused to surrender his books, holing up in a house described as “an arsenal.” He swore the re-election ousting him had been rigged, that more ballots had been counted than persons present in the room and that some lived outside the district or had not lived at Cripple 30 days—the more things change, the more they stay the same. In December, a man was killed on his sled, with his two partners, guns and provisions missing mysteriously, since they shared three prospect pits and a fine house, a tower made mainly of sod. Petty criminals prospered as well. Joseph Carroll, a fleet mail carrier and expert trailsman, absconded with three dogs and the wrong sled. He’d been in a bad frame of mind for a day or two, it was said. Thieves wheelbarrowed coal away, and from a permafrost cache, snatched 20 sacks of flour and 17 dressed chickens saved for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Brazen burglars slashed tent sides, pumping in chloroform to rob marks the moment they fainted.

The daughter of a Russian trader and Eskimo mother, Changunak Antisarlook Andrewuk, “Sinrock Mary” or “The Reindeer Queen,” at one point owned Alaska’s biggest reindeer herd—the government six years earlier had launched a program to convert starving Inupiaq seal and walrus hunters into capitalists, recruiting “Laplanders” as instructors. Rumrunners and grifters connived to cheat Changunak out of her wealth. Prospectors slandered the imposing, curly-haired woman who adopted orphan survivors of epidemics. They threatened and sued her, harassed her deer, scattering them, and shot some they left rotting on the tundra. They offered liquor to cloud her judgment. Miners staked turf inside grazing ranges, torched vegetation to clear ground, destroying forage, and, having eaten or scared off all game, rustled the reindeer.

Rex Beach, having encountered Nome’s misfits, fictionalized some in The Spoilers, which saw five screen adaptations. (The wartime one starred Marlene Dietrich and John Wayne.) “Yellow Kid,” operating a gold scale, smoothing his hair often, harvesting ounces of “trading dust” after each shift from his head brilliantined with syrup, perhaps was invented. Beach’s real-life foils included an embezzling postmaster, a tax assessor nabbed for shady financial deals and a crooked federal judge. Protection moneys changed hands where bar owners ruled the city council. Gold, driving all, in Thomas Hood’s words was “Heavy to get, and light to hold; Stolen, borrowed, squandered, doled.”

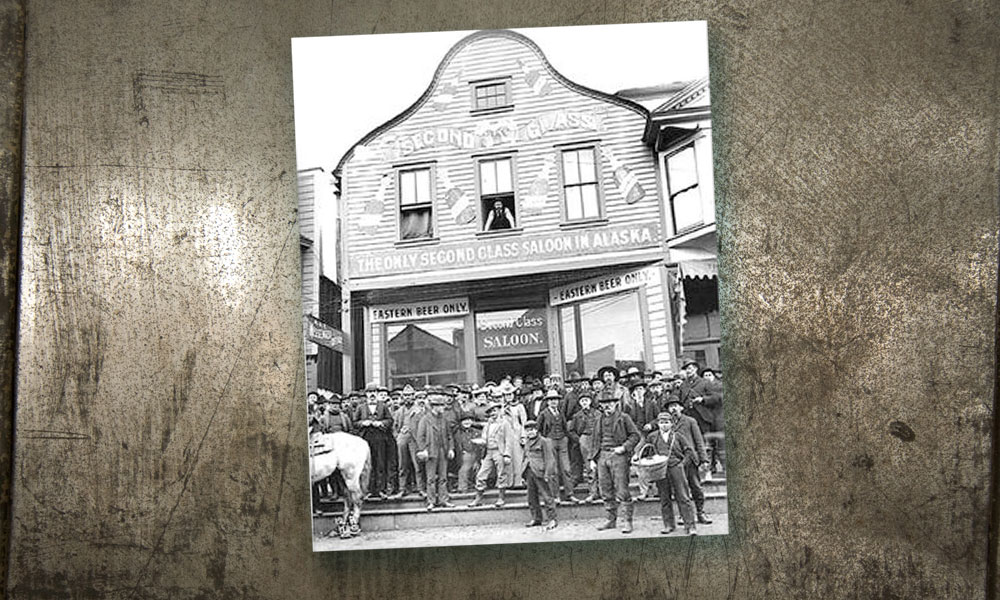

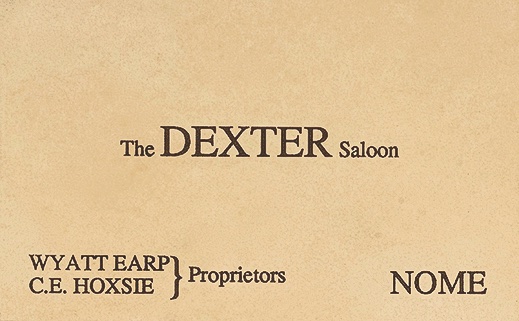

And squander they did. Saloons mushroomed seemingly overnight, 42 by one count, over 60 by another, among them Earp’s Dexter, Rickard’s Northern, Charles Cobbs’s Horseshoe, William Robertson’s Eldorado and, one of Nome’s finest, the Second Class Saloon. Dick Dawson owned it with partners—plush Brussels carpets, electric lights, Eastern Beer Only, the extravagance of a sewer, and all. Dawson felt every saloon-man but him bragged about running a first-class establishment, hence the tongue-in-cheek advertising of his. The Nome Gold Digger, one of four local papers, broadcast news about epic gaming sprees, noting that keno caught on at the Hunter “like an epidemic of the measles” or that an Eldorado crap session run haywire forced the dealer to upend his cash drawer on the table to prove the bank had really been busted.

Glimmers of Hope

The clink of coin wasn’t always so crass. The first baby born amidst it, to an ex-whaler and a sister of Sinrock Mary in the Eskimo camp on the Snake River spit, was christened Nome, and the proud father reserved a claim for him. A fox-robe fundraising raffle, a free Thanksgiving meal at the Northern, a club supporting Scandinavians, miners’ grassroots meetings, the odd Congregational service, and Literary Society debates and recitals sounded social grace notes. The “flying Dutchman” Carl von Knobelsdorff en route to San Francisco dropped off mail for miners still stuck in Dawson or Skagway. The previous fall, he’d ice-skated on dulled whipsaw blades hundreds of miles between Kobuk River camps, delivering newspapers and letters for $1 each. Rumors and gossip he carried for free. Dressed in knee-high, checkered socks, wool cap, sweater and mitts, a pack with sleeping roll on his back, pistol and hunting knife on his belt, the bearded Germanic Hermes swung a metal-tipped pole for propulsion and balance.

This newest migration, word of which Knobelsdorff had helped spread, swamped the “Poor Man’s Diggings,” because on the public beaches no man—or woman—had to stake or register claims. No ground had to be thawed out either. “Besides the rich ruby [garnet] sand,” the news crowed, “there is coarse gold, it may be in large amounts.” Latecomers marveled at damsels in flowerpot bonnets and ankle-length skirts over petticoat layers feeding rockers and sluices with shovels of muck. “For many miles along the beach double ranks of men were rocking, almost shoulder to shoulder…passing jokes or singing as they worked,” a US Department of Labor agent reported.

Courtesy of Carrie M. McLain Memorial Museum

Instead of streets paved with gold, five-year-old Klondy Nelson, joining her father (a Klondiker) on Ophir Creek, saw “an ugly blanket of soft-coal smoke hanging low over everything.” Homesick miners there paid a herder to play Santa for Klondy and gave her nuggets as presents.

True whoppers lay in them thar hills. Until 1989, a slug from Anvil Creek’s Number 5 Bench weighing as much as a gallon of paint held the title of largest lunker unearthed in Alaska. The district also coughed up the sixth-, seventh-, ninth-, and tenth-ranked ones. By century’s turn, the Bering Strait fields already had yielded $3.5 million, and the next two decades netted another 80 million.

The Dark Side of Dreams

The glitter hid grimmer realities. Behind Nome’s false-fronted boxes lay dozens of prostitutes’ cribs fenced off in the “Stockade” with their own phone system and messengers. Women billed as “actresses” or “vaudeville entertainers” worked at saloons where their popularity boosted lucrative sidelines. “There were more of these in Nome than in any mining camp I was ever in,” Trelawney-Ansell recalled. “Nothing in the worst days of Montmartre in Paris, or on State Street, Chicago, ever paralleled the shows given here.” Cigar stores too could serve as a front for ladies of the night. A few escaped this meat market. “Charlie the Bear made off with Halibut-Face Mary. A stinker named Misery Chris eloped with Toodles, and the King of Denmark stood up before the preacher with Deepwater Dorah,” wrote Frank Dufresne, Klondy’s future husband. As town got more civilized, the retirees’ primrose past was forgotten or politely ignored, since “in almost every case the old dance-hall habitués became the strictest sort of wives.”

“Japanese Mary” was less fortunate. Ever the sporting woman, she bet $1,000 on a compatriot in the winter marathon held on an indoor track and invested her winnings successfully by grubstaking prospectors. She was found strangled with a towel and shoelace, a gold-nugget necklace with a cross and all her money gone from her hutch. The demimonde dames were tough, though. They drugged and rolled Johns or rigged scales weighing payments for services rendered. Daisy Straws, “of evil repute,” for reasons unknown in the street brained a man with a hammer, but a soldier broke up the fight. In extremis, morphine or opium made life bearable—or ended it.

Nome’s grand jury recommended that to curb sin, women should be barred from saloons and those without visible means of support be watched and, if lacking decorum, prosecuted. Raiding the red-light district, the Law threatened prostitutes with arrest unless they paid a $10 “fine” that funded the fire department and police. Military patrols enforced compliance with public health regulations. A “pest house” for medical outcasts quarantined for smallpox had sprung up a mile and a half away. The Army also expelled people without lodging or means to procure it before winter’s onset.

The Call of the Wild

Wyatt Earp, homeless in a different sense, was 52 when he disembarked in Nome. Though his walrus moustache showed streaks of silver, he’d not reformed into a proper senior citizen. The aging gunslinger traveled with his common-law wife Josephine “Sadie” Sarah Marcus Earp, a gambler and former dancer and “good-time girl” still a beauty at 37. Her gambling habit ran rampant in Nome until Wyatt cut off her funds and asked fellow barmen to do the same. An octagonal bone chip, if authentic, suggests that he signed some of the Dexter’s custom-made gambling chits, which he handed to desirable customers in lieu of his calling card while he roamed town looking for Sadie or on business. These could be redeemed for a drink. Other establishments used trade tokens for liquor or dances with girls. (In a pinch, male partners sufficed.)

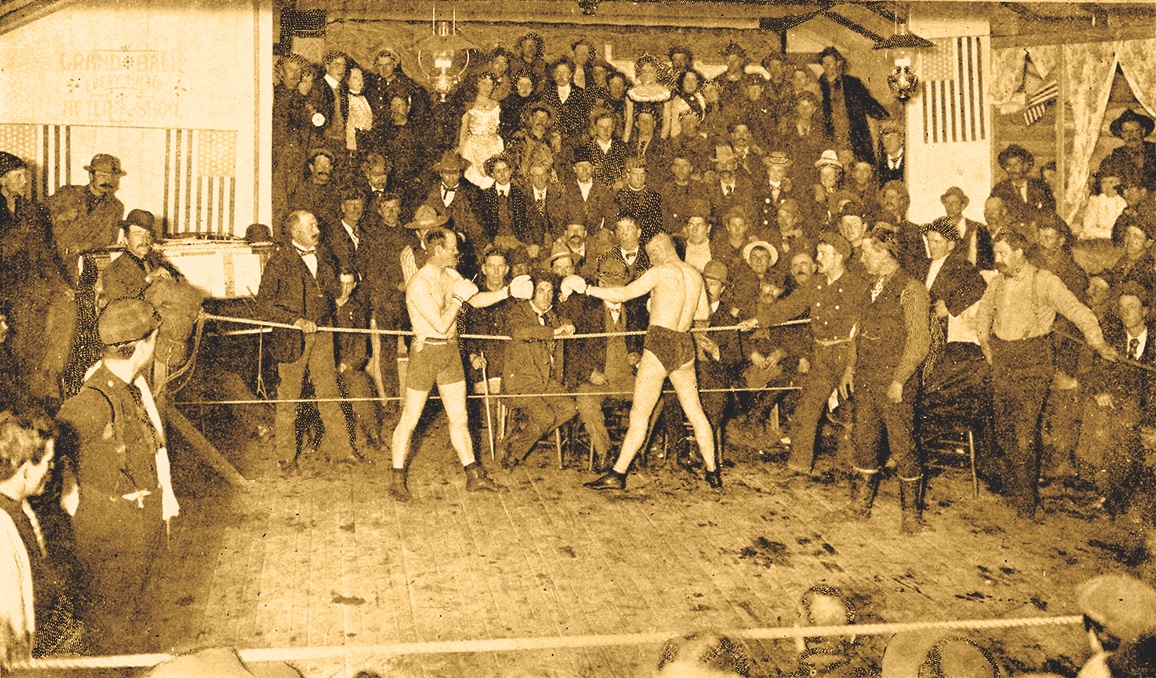

In 1897 the couple had heeded gold’s call. Two years later Earp and partner Charles Ellsworth Hoxie had built the Dexter, Nome’s first two-story wooden showpiece. Among the town’s largest, poshest saloons, it sported 12 “clubrooms” upstairs. Under 12-foot-high ceilings, miners went broke playing faro, monte, blackjack or billiards. Across from the Dexter, Rickard at the Northern banked on a “scientific mixologist” bartending below nude paintings, but foremost on roulette and bare-knuckle prizefights. (He would go on to become a Barnum-like Madison Square Garden boxing promoter, staging Jack Dempsey in the first boxing match to attract a million-dollar crowd.)

Eric A. Hegg Collection, University of Washington

On slow days, Earp walked the cratered beach, plinking whisky bottles he threw in the air. After a drink or two too many, he once “got the idea he was a bad man from Arizona and was going to pull some rough stuff,” according to B. D. Blakeslee, a civil engineer mapping the region. Marshal Albert Lowe simply slapped the erstwhile terror of cowhands’ face and took his hog leg. He asked Earp to go home, to bed, or he would run him in.

In 1901, the year before the Fairbanks gold strike, Earp and Sadie returned to California $80,000 richer—Locomobile’s steam chaise, a primitive car, at the time cost $600. The year after, they moved to Nevada, where another bonanza, more brawls and yet another den of iniquity beckoned. By 1915, Earp had drifted into Hollywood, trailing Jack London, whom he knew up north, having wintered at Rampart on the Yukon River when London left the Klondike luckless and wan but brimming with stories. One day, both were dining with one-time cowboy, sailor and movie actor-turned-film-director Raoul Walsh. Before long, the world’s highest-paid entertainer and future star of The Gold Rush sauntered over. “You’re the bloke from Arizona, aren’t you?” Charlie Chaplin said to Tombstone’s ex-deputy marshal with evident awe. “Tamed the baddies, huh?” He then looked at London and nodded. “I know you, too. You almost made me go to Alaska and dig for gold.”

Michael Engelhard lived briefly a block up the street from the Discovery, now a private residence, finding the town’s liquor too expensive, the churches too many, the wind too atrocious.