Roys Oatman and his family have just finished hauling their belongings up a rocky grade to a bluff on the south side of the Gila River. At the end of this long day, the Oatman oxen are bone tired and so is the family.

Roys’ 38-year-old wife, Mary Ann, is eight-and-a-half-months pregnant, and she has just enough strength to prepare a pot of bean soup and some bread for the family to eat before they continue on. The family intends to travel all night to avoid the heat of the day. They are 120 miles from their destination.

The oldest boy, Lorenzo, 14, is loading up the last of the baggage in the wagon, when he turns and sees “several Indians slowly and leisurely approaching us in the road.”

Lorenzo later says they converse“with father in Spanish” and “made the most vehement profession of friendship.”

Roys is not armed. He has a rifle, but it is in the wagon. The Indians, thought to be Yavapais, ask for tobacco and pipe, which Roys promptly produces. After the warriors finish smoking, one of them mentions seeing “two horses down in the brush.” (An American traveler later reports that his two horses had been stolen the day before.)

The Yavapais ask for pinole (corn meal). Roys protests that he doesn’t have enough to give away, but they persist, and he reluctantly gives them some bread, which they eat. Then they ask for more.

— Published in Captivity of the Oatman Girls by Royal B. Stratton —

When Roys tells them that he doesn’t have any more, a Yavapai brazenly walks over to the wagon and climbs in the back, rummaging around inside. When he comes out, he demands meat.

The emboldened Yavapais start taking objects from the wagon and stuffing items in their clothing. When the family protests, the Yavapais withdraw a few paces and begin talking in their native tongue. Essentially, they are divvying up who will kill who, and who to spare.

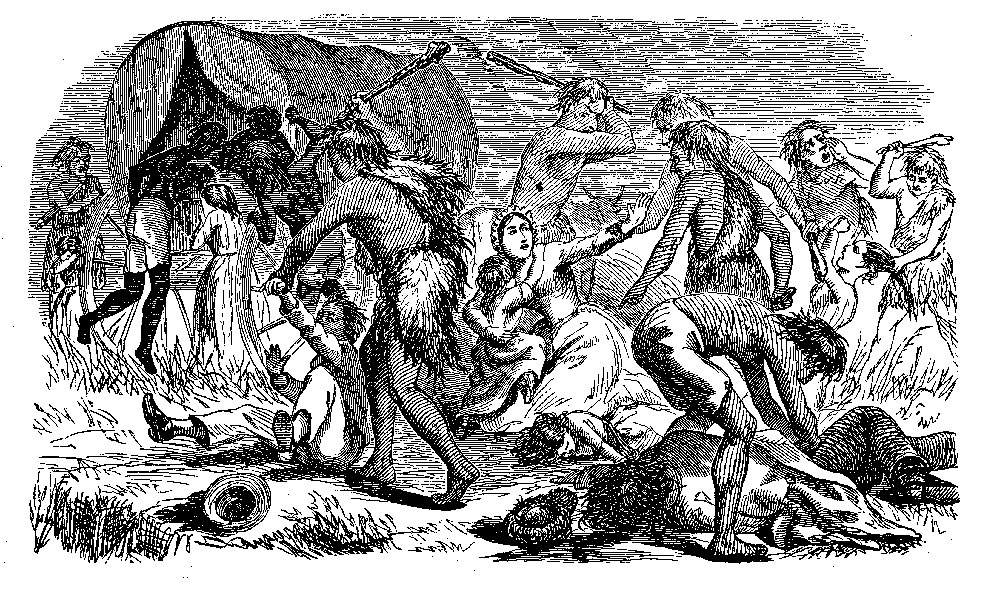

Roys tries to keep calm and starts reloading the wagon. At this point, a Yavapai lets out a “deafening yell,” and each warrior attacks a member of the family with a war club.

Roys, his wife, his daughters Lucy, 16, and Charity Ann, three, and his sons Roys Jr., five, and Roland, two, are brained senseless, falling to the ground. Lorenzo is also bashed on the head. With blood streaming down his face, he half-runs, half-stumbles toward the edge of the bluff and falls over the side.

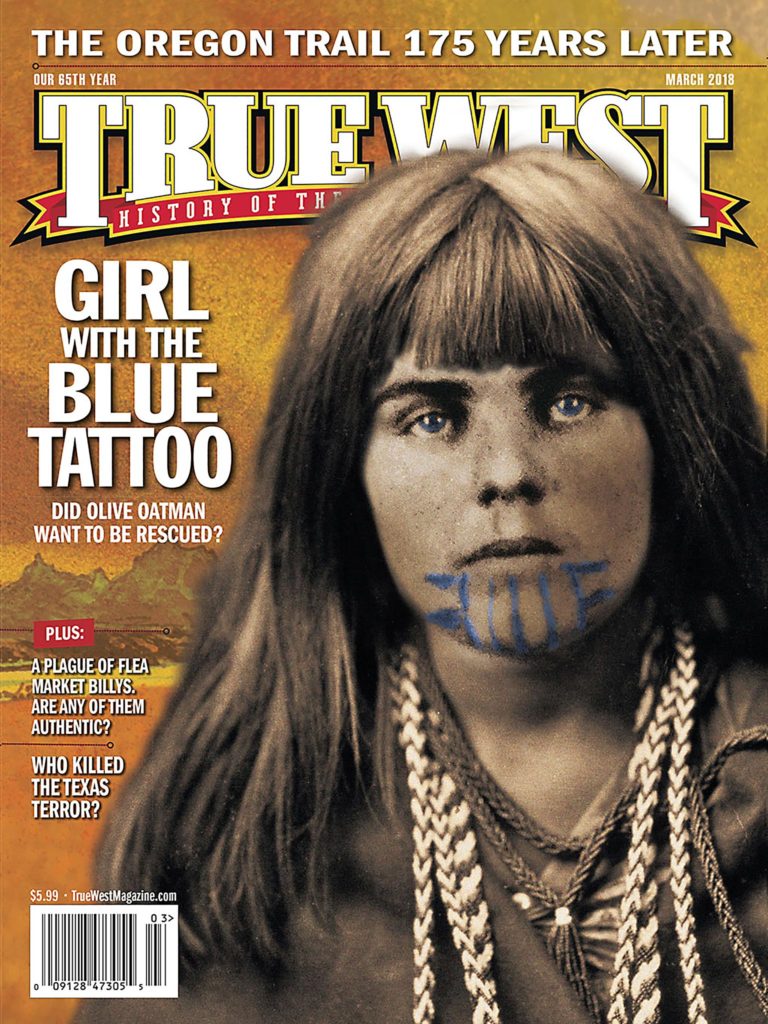

Only two are spared: Olivia, 13, and Mary Ann, eight, who are forced to watch the warriors strip their family’s dead bodies, looking for items of value. They take the wheels off the wagon and tear the canvas canopy off its frame. While breaking open boxes, the raiders also tear a feather bed, scattering its feathers to the wind.

The Yavapais unhook the oxen, bundle up their plunder and rudely push the girls in front of them. They take the sisters’ bonnets and shoes, and force the girls to walk barefoot toward the Yavapai camp, some 90 miles away.

Olive Describes What Happens Next:

“After we had descended the hill and crossed the river, and traveled about one half of a mile by a dim trail leading through a dark, rough, and narrow defile in the hills, we came to any open place where there had been an Indian camp before, and halted.

“The Indians took off their packs, struck a fire, and began in their own way to make preparations for a meal. They boiled some of the beans just from our wagon, mixed some flour with water, and baked it in the ashes.

“They offered us some food, but in the most insulting and taunting manner, continually making merry over every indication of grief in us, and with which our hearts were ready to break. We could not eat.

“After the meal, and about an hour’s rest, they began to repack and make preparations to proceed.”

—Olive Oatman, describing the first grief-stricken moments of her five-year ordeal.

For almost a century, historians thought the raiders were Tonto Apaches and that they took the Oatman girls into the Tonto Basin area. Historians now believe the raiders were Yavapais, and that they took the sisters to a mountain camp in the Harquahala mountains.

Since the Apaches did not traditionally trade with the Mohaves, where the girls ended up, the Indians were probably Yavapais, argues Brian McGinty, in The Oatman Massacre.