— Paxson oil Courtesy Whitney Gallery of Western Art, Buffalo Bill Center of the West —

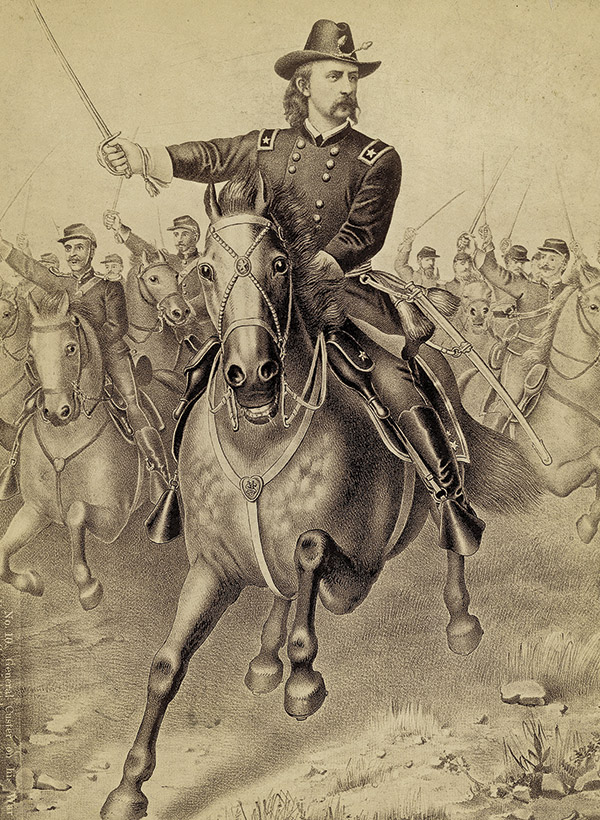

Tragically dying on June 25, 1876, with his men at his last battle, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer has lived on as an integral part of America’s cultural heritage. Out of the mire of speculation about the 7th Cavalry leader’s motives and his alleged disobedience of orders, battle researchers have uncovered this collection of crazy facts about the tragedy that history so often records as Custer’s Last Stand.

— Courtesy National Park Service —

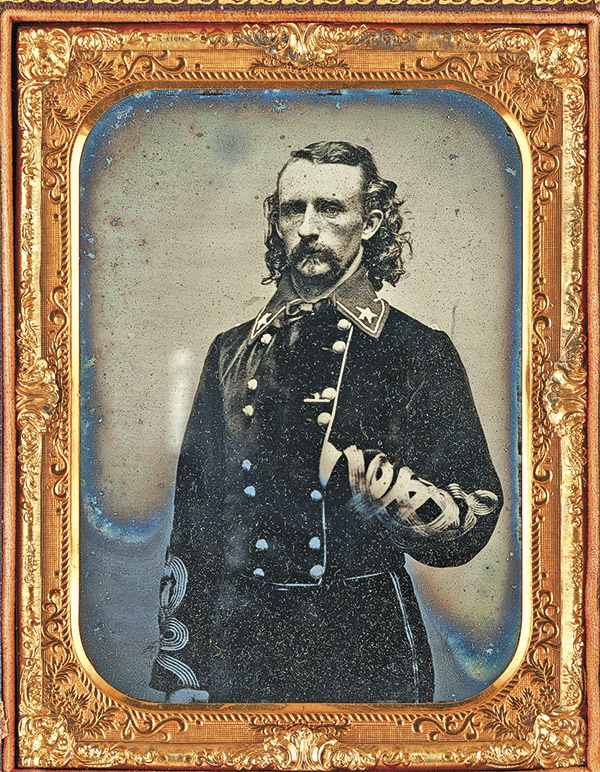

What did Custer wear?

“The Indians at the Little Bighorn [sic] may have done Custer a perverse favor with their victory over him and his men,” Michael Elliott observed in Custerology. “His spectacular death preserved him for the ages as a symbol whose meaning and significance could be endlessly disputed. Custer’s trials would continue long after his death, in the halls of history, where Custer always belonged.”

But artists have done history a disservice by portraying Custer wearing a buckskin jacket, in nearly 100-degree weather, holding a saber and being felled by a lance. Two bullets actually ended his life.

If Trumpeter John Martin is correct, Custer did not wear his buckskin jacket when he rode to battle at the Little Big Horn. That day, he carried a Remington sporting rifle, a hunting knife and two British revolvers. With the possible exceptions of Lts. Charles C. DeRudio and Edward G. Mathey, the 7th Cavalry was not armed with sabers that day. Death by lancing is not a likely scenario.

What book was Tom Custer reading when killed?

Canadian colleague George Kush reports Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner’s 1873 novel The Gilded Age “was the book Capt. Tom Custer was reading when he was killed at the Little Big Horn. He was almost finished and promised to loan it to another officer, also killed on June 25, 1876.”

Did Army-supplied rifles kill Custer and his men?

A True West reader told Marshall Trimble that President Ulysses S. Grant had ordered lever action rifles for Lakotas that they used against Custer at the Little Big Horn battle. He never heard this before; neither have I.

Prior to the battle, Gen. George Crook and other officers had accused Lakota agents and traders of supplying ammunition—not firearms—to “hostile” tribesmen, backed up by reports like one given by Standing Rock Agency Capt. J.S. Poland.

The Indian Office ordered such ammunition transactions to cease, a move casting doubt that Grant ever provided lever action rifles to Lakotas. The reader’s question defies logic because the President authorized, if not initiated, the Sioux War of 1876-77, and these repeaters and any other firearms would have been used against the U.S. Army.

Archaeological evidence does show Little Big Horn warriors carried repeating firearms. Lakota Chief Sitting Bull and his band avoided the agencies, but obtained arms and ammunition from Métis traders, Sitting Bull biographer Robert M. Utley states. Discovering who supplied repeaters to Lakotas and Cheyennes requires further research.

— Adams poster true West Archives —

Were battle accounts rewritten?

Frontiersman George Herendeen provided articulate, comprehensive accounts of the Little Big Horn battle, including a New York Herald letter published in 1878. Yet his letters at the Montana Historical Society indicate he was barely literate. What gives?

“His” Herald accounts appear to bear the fingerprints of Maj. James Brisbin, a voluminous author who wrote at least one 1876 campaign dispatch for the Herald, while commanding the 2nd Cavalry of Col. John Gibbon’s Montana Column. Brisbin probably transcribed—and embellished—Herendeen’s interview statements.

Author James W. Schultz left his mark on scout William Jackson, whose 1890s statement at the Military History Institute features edits that “include lining through words and replacing with better descriptions, adding in phrases and, in at least one case, deleting whole sentences and rewording the text,” Col. Samuel Russell says.

Two different versions of Jackson’s account, both written in the first person by Schultz, were published: one in the Los Angeles Times in 1914 and the other in the 1926 biography William Jackson: Indian Scout.

The earlier account takes “serious issue with interpreter [Fred] Gerard, intimating that he was a coward throughout the event. I suspect that this favors Schultz’s view of Jackson rather than Gerard’s,” Russell says.

Reserve the most caution for soldier accounts “told” long after the event. Researcher William J. Ghent claimed Pvt. William Slaper did not write “his” account published in E.A. Brininstool’s 1925 tome A Trooper with Custer. “It was written by Mr. Brininstool, as Mr. Slaper himself told me…. [It is] about 75 percent Brininstool and only about 25 percent Slaper.”

Did the daughter of a Little Big Horn survivor lie?

Among the 7th Cavalry-related books quoted as a reliable source is the memoir With Custer’s Cavalry by Katherine Gibson Fougera, daughter of Lt. Francis M. Gibson. Yet British colleague Peter Russell’s research confirms suspicions concerning the story’s faithfulness.

For example, a comparison of Gibson’s July 4, 1876, letter published in the memoir with a transcription of the original document in the Gibson-Fougera Collection at Little Bighorn Battlefield reveals word additions, changes and omissions, and a few factual errors. Such edits might be excused if not for the flagrant insertion of several sentences that do not appear in the transcription, claiming that Gibson heard Lt. George D. Wallace’s well-known premonition, on June 22, 1876, of Custer’s death. The daughter’s spurious addition represents an insidious attempt to misrepresent Gibson’s mindset, if not to distort his performance, at the 1876 battle.

Perhaps the daughter learned this premonition from a similar account, published in Capt. Edward S. Godfrey’s 1892 Century article and noted in his diary, which, however, did not confirm Gibson’s presence during the episode.

Fougera’s memoir is an easy read, but should be regarded as historical fiction.

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, November 11, 2007 —

Did the search for gold bolster Custer’s confidence?

When Custer entered the Black Hills for his 1874 expedition, he might have been aware of a prior gold expedition—a party of 150 prospectors from Bozeman, Montana—that had successfully engaged Lakotas and Cheyennes in the valleys of the Rosebud and Little Big Horn on several occasions. The saga arguably reinforced Custer’s confidence that the 7th Cavalry could whip the Indians too.

Custer’s crew was officially searching for a suitable site for a fort (the future Fort Meade) for the Army to monitor and control Lakota movements. Yet the expedition may have spurred an unintended consequence.

— Courtesy The Russell, March 17, 2018 —

Although the Bozeman crew never found gold and looking for gold was not part of Custer’s stated mission, news of such a discovery in the Black Hills prompted a rush there that not only successfully resulted in gold, but also antagonized the Sioux, producing the Sioux War of 1876-77. Labeling the Sioux as “hostiles” solved President Ulysses S. Grant’s dilemma of how to allow whites to exploit territory promised in Indian treaties.

Who discovered the dead on Custer’s Battlefield?

More than one enlisted man claimed, without confirmation, to carry a dispatch from Maj. Marcus A. Reno to Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Terry on June 27, 1876, marking each one as possibly the first, if not the first, member of the military to discover the dead on Custer’s battlefield.

A private, Henry Brinkerhoff, claimed he found a “bunch of seven soldiers, killed, stripped and scalped, and several gray horses—dead—showing they belonged to E Troop.”

William Baker claimed Reno had dispatched him and Arikara scout Young Hawk to procure medicine from the steamboat Far West. They found two bodies after crossing Medicine Tail Coulee, he told battle researcher Walter Camp, before “Bradley and two or three scouts came along.”

James H. Bradley, the lieutenant chief of scouts of the Montana Column, is traditionally the soldier credited with first finding the Custer dead, an event documented in his journal.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Yet Young Hawk did not mention Baker or the boat mission to Camp. He later told O.G. Libby that Reno had ordered him and Arikara scout Forked Horn (not Baker) to meet the Montana Column on June 27.

A 2nd Cavalry first sergeant, Frederick E. Server, told Camp that, on June 27, he and a Crow scout “were the first to discover the dead on the Custer battlefield. As soon as they found the dead, he [Server] wrote a note and sent it to Gen. Terry.”

Custer’s chief of scouts, Lt. Charles A. Varnum, recalled a failed attempt to “carry the news & try to get relief” after the fighting had ceased on Reno Hill on June 26. “They [the scouts] brought back the dispatches and said there were too many Indians.”

Varnum’s account suggests Reno sent multiple messages. Young Hawk confirmed messages had been “written for each of the scouts,” which he, three other Arikaras and a sergeant failed to deliver after “Dakotas fired on them.”

One thing is clear: Reno wrote a message on June 27 informing Terry of a “most terrific engagement with the hostile Indians” and requesting “medical aid at once.” This dispatch is securely stored in the National Archives.

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 11-12, 2012 —

Did Custer and Benteen argue over dividing the ranks?

Custer and Capt. Frederick W. Benteen discussed the wisdom of dividing the regiment before the 7th Cavalry marched to destiny at Little Big Horn. That is, if you believed the encounter re-created in 1991’s Son of the Morning Star.

The ABC miniseries’ dialogue quoted, almost verbatim, what battle survivor Charles Windolph told Frazier and Robert Hunt in the 1940s:

“I heard Benteen say to Custer: ‘Hadn’t we better keep the regiment together, General? If this is as big a camp as they [the scouts] say, we’re going to need every man we have.’ Custer’s only answer was: ‘You have your orders.’”

Yet the closest Benteen came to any such caution was an 1890s remark to Theodore Golden: “That is all I blame Custer for—the scattering, as it were, (two portions of

his command, anyway) before he knew anything about the exact or approximate position of the Indian village or the Indians.”

If Benteen had advised Custer to “keep the regiment together,” he would have so testified at the 1879 Reno Court of Inquiry or reported the encounter to Custer’s superior,

Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry, or mentioned it when responding to criticism of his own actions at the Little Big Horn battle.

Earlier, in 1909, Windolph did not mention this Custer-Benteen encounter to Walter Camp. A Medal of Honor recipient for his actions as a private at Little Big Horn, Windolph may be excused for his fuzzy memory some 60 years after the battle.

Windolph told the Hunts he had approached Benteen for permission to exchange horses with First Sgt. Joseph McCurry, when he overheard the alleged conversation with Custer. The social structure of the post-Civil War frontier Army casts doubt on Windolph’s story. The stratified military system separated enlisted men from their social and intellectual “superiors,” Kevin Adams documented in Class and Race in the Frontier Army. Company commanders delegated day-to-day management to their first sergeant (for example, McCurry) and other non-commissioned officers.

Sometimes Westerns are not entirely at fault for failing to portray an incident accurately. Son of the Morning Star fell into the trap of relying on an unreliable battle participant.

Was Custer impulsive or a great cavalry officer?

The peace-time Army’s mundane routines following the Civil War’s glories probably explained much of Custer’s post-war legacy, his later accomplishments and frustrations, if not the outcome of the Little Big Horn battle.

“War,” T.J. Stiles observed in Custer’s Trials, “gave Custer his greatest pleasure. It gave him purpose, praise, and the adoration of his men. Whatever would he do when peace returned?”

After Custer’s death, a letter in the Army and Navy Journal noted: “Gen. Custer may have been too impulsive, but after all the great forte of cavalry is reckless dash. Custer’s only fault, if fault it may be termed, consists in failure. If it [the Little Big Horn] had been a success, as doubtless he had every reason to anticipate, imperishable laurels would have crowned his brow.”

Custer earned a reputation for rash, insubordinate action in battle and elsewhere, yet he also could accurately assess tactical battlefield situations and react instantly, often with success.

On the other hand, he did demonstrate restraint against unfavorable odds or a trap, as he showed at the 1864 Battle of Trevilian Station, the 1868 Washita fight and his 1873 skirmish with Lakotas along Yellowstone River.

Whether or not Custer’s alleged disobedience of Gen. Terry’s instructions on June 22, 1876, played a central role in how the Little Big Horn battle played out remains a ceaseless controversy. But that is a story for another day.

C. Lee Noyes and wife Michele edited The Battlefield Dispatch for the Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association for 15 years before retiring in 2016.

They continue to disseminate information on late 19th-century Plains Indian Wars. For further Little Big Horn battle research, Noyes recommends you read James Donovan’s A Terrible Glory, Nathaniel Philbrick’s The Last Stand and Robert M. Utley’s Custer and the Great Controversy.