Reading the pulp westerns and watching B-westerns one might conclude that the Colt revolver was the only pistol used in the Old West. Remington built a fine six-shooter and so did Starr and Smith & Wesson. At times Wyatt Earp carried a Smith & Wesson. Frank James packed an 1875 model Remington and also owned a Smith & Wesson Schofield, as did his brother Jesse. Buffalo Bill Cody was also a great admirer of the Smith & Wesson revolver. Besides his trusty Colt, Jesse James carried a .44 Starr revolver.

The Army gave rigorous tests to several revolver-making companies. Other brands were superior to the Colt in some tests but for overall ruggedness, design, reliability and simplicity of design, none could compare with the Colt.

The revolver was designed for close-quarter fighting. An experienced gunman was considered proficient if he could hit what he was aiming at in a distance of fifteen yards. Since the rifling in the barrel twisted to the left, the bullet would also drift some 30 inches in 300 yards no matter how good the shooter was. Its maximum effective range was 75 yards. At fifty yards it was considered good shooting to group the shots in a six-inch circle. But it could be effective at long range. The army tested the Peacemaker and found that by allowing for trajectory, the point of aim at 150 yards should be 4 feet above the target and at 200 yards one had to line the sights up 8 feet above the target.

In 1878, the .44 caliber Colt came on the market. It was popular among westerners because most also carried the Winchester Model 1873 .44-40 in their scabbard. That way one needed to pack only one kind of ammunition for both pistol and rifle.

Black powder was used until the 1890’s and it threw out large puffs of white smoke that could that could quickly engulf a saloon. That might explain why some of the shooting seemed so poor. A gunfight in the Long Branch Saloon in Dodge City on April 5th, 1879, is a good example. Cockeye Frank Loving and a buffalo hunter named Levi Richardson got into a row, chasing each other around a gaming table, shooting all the while, their pistol barrels almost touching. Richardson, fanning his pistol, fired all five rounds, missing five times, succeeding only in setting Cockeye Frank’s clothing on fire. His clothes trailing smoke, Cockeye finally hit Levi with a fatal bullet.

One couldn’t always count on the cartridges to explode. When Jack McCall shot Wild Bill Hickok in Deadwood on August 2nd, 1876, the pistol he used misfired on every cartridge in the cylinder except the first one–the one that fired the fatal bullet.

The two-gun fighter was mostly a creation of Hollywood. Few could do any more than waste ammunition with their off-hand. Even the ambidextrous Hickok wasn’t as good with his left hand. During a shooting exhibition when the left hand didn’t perform as well as the right, his only comment was he’d never shot a man with his left hand anyway. The real purpose of a second gun was to have a weapon in reserve. In the early days of the revolver extra weapons were carried because it took a painfully long time to reload. If they didn’t carry extra pistols, they often had an extra cylinder or two loaded and ready to insert.

One of the reasons for the Colt’s popularity out West was that if any part of the weapon was broken, it would still function. Texas Ranger Captain John (RIP) Ford wrote that during the Battle of the Frio, in Texas in 1866, the hammer of ranger, Sam Walker Trimble’s (this writer’s great-grandfather) Colt revolver broke and he was still able to fire his weapon by using a small hand-held tack hammer to strike the percussion cap.

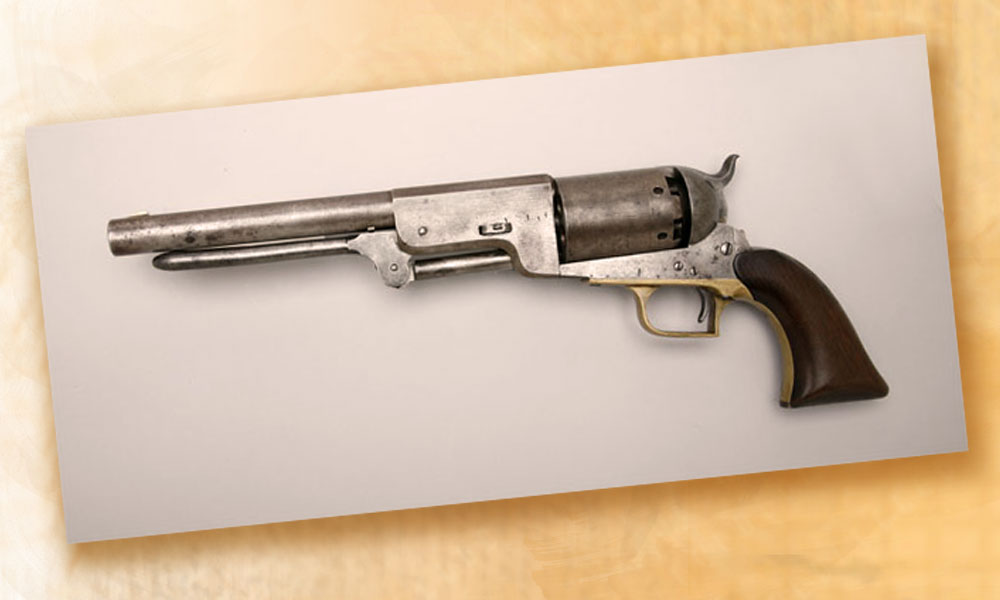

Before long other manufacturers were producing good revolvers to compete with the Colt. In 1858, Remington produced a single-action revolver with a solid-frame strap over the cylinder which gave more strength and a continuous sighting groove. Five years later a new model came out with several modifications that resulted in the popular .44 caliber New Model Army.

Smith & Wesson developed their famous No. 3 single action (SA) revolver around 1868 and it remained in production until 1898.

In 1870 Major George Schofield, an officer in the U.S. Cavalry, redesigned the No. 3, improving it in several minor and one major way, reputedly for mounted use. It was the Schofield version that ensured the revolver’s lasting fame.

The S&W Model 1875 Schofield, like any single-action revolver, the No. 3’s hammer had to be manually cocked before the weapon could be fired. There is no side-loading gate or external ejector rod housing on a No. 3. Instead, it was a top-break design.

The principle advantage of this design is that all fired brass can be removed simultaneously. (Actually dumped out, since there is no ejector.)

Starr came out with a revolver during the war that was more rigid than the Colt and had a top strap across the cylinder similar to the Remington. It was also easier to break down to remove the cylinder. Despite this, the .44 Starr never did gain universal appeal among Westerners.