Ella La Rue and the Performing Variety of Women of the Old West

Historian Jill Lepore recently observed that microhistories of unknown people find their lives serving as allegories for the larger American culture; a microhistory of one life takes us closer to the lives of many. The often nameless, largely forgotten women of the Old West’s variety stage lived their struggles in ways singular yet representative of many.

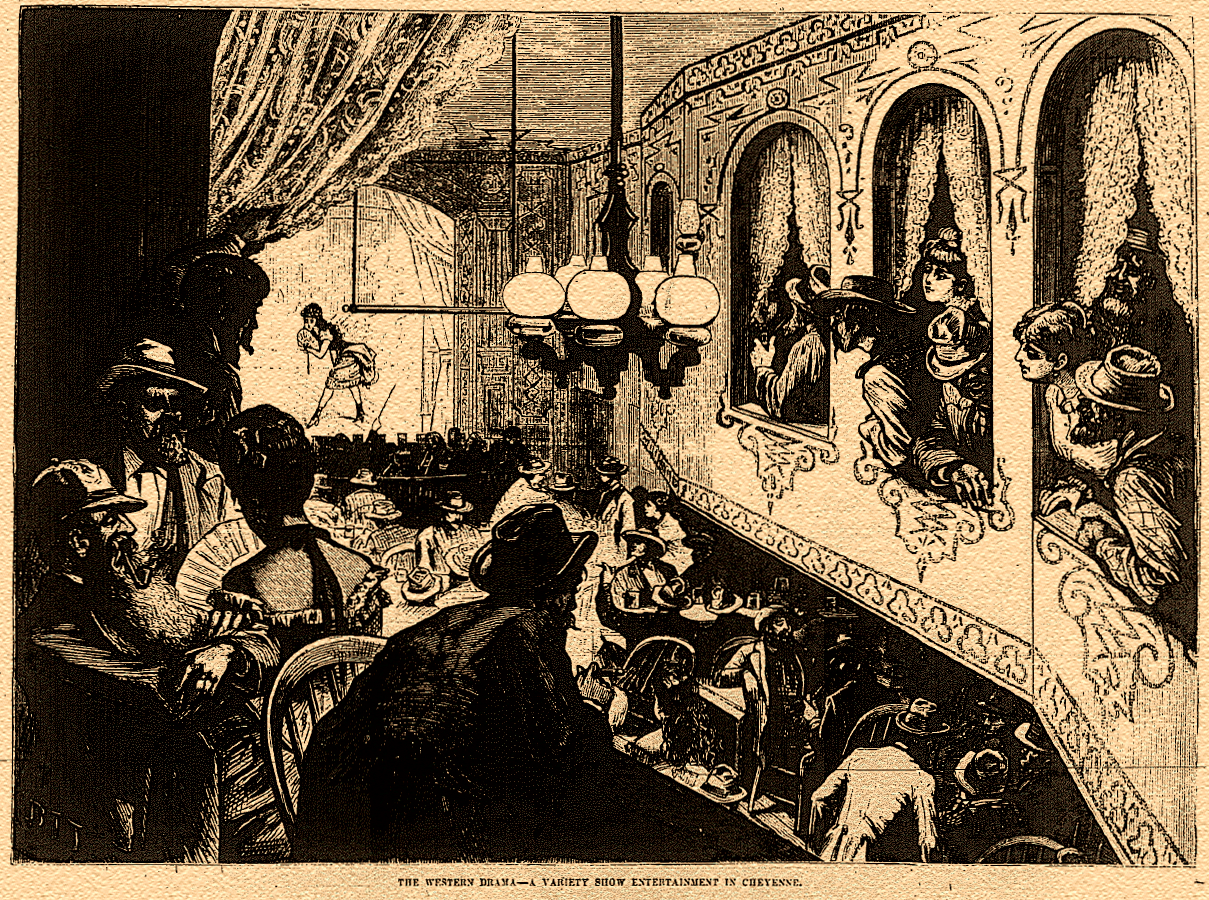

Performing women—singers, dancers, and the like—came from saloon owners’ needs to keep a largely male population happy. The saloon in the Old West was a male institution but found the use of waiter girls and women who sold companionship a complement to the liquid refreshment offered. Pretty waiter girls took a turn onstage in seductive costumes that encouraged male patronage, becoming the first entertainers in many a Western settlement. Coy, flirtatious behavior coupled with liquor and an environment of merriment enhanced by music, minstrelsy, salacious theatricalities and short skits became variety theater in the mid-1800s and later in the century morphed into vaudeville. For some women, variety performance became an avenue to self-realization, wealth and fame.

Ella La Rue mastered her own narrative by subverting traditional feminine performance codes and gendered expectations. She embraced the mobility needed to traverse the far-flung towns of the West, and she sold sexuality rather than sex.

The “queen of the banjo” first opened in San Francisco’s Olympic variety theater in mid-1866 in musical skits based loosely on minstrelsy, then toured the interior melodeon theaters, performing in farces and skits, in addition to singing and dancing. The consummate performer, she was billed as “The Startling Sensation, Ella La Rue in Mazeppa or the Wild Horse of Washoe,” in one of her most famous impersonations. La Rue burlesqued the story of Mazeppa based on a romantic poem by Lord Byron. The erstwhile lover, a young man, is punished by being stripped naked and tied to the side of a horse to roam Eastern Europe in a melodramatic story of suffering and near-death experiences. When it was performed on stage, La Rue was tied to a live horse and sent on a wild ride into the hills, simulated by ramps painted as mountains. The spectacle of the almost nude woman dressed in flimsy flowing gauze and pink or flesh-colored tights, drew on audience voyeurism, and was the true draw of both serious and burlesque renditions of the Mazeppa role.

Ella’s early years demonstrate several themes that would hold true throughout her career as well as those of other female variety stars. The variety stage required versatility with multiple performance genres including music, burlesque and derring-do, as well as using the distinctive female form as a titillating advantage in selling sexuality to the men who frequented the West’s melodeon saloons.

Women in the Victorian mindset were stereotyped as either respectable “true women,” who needed to be protected by a man, or temptresses who needed male control. Variety stage women like Ella La Rue were neither, but as sexualized variety performers they were able to parlay beauty, multifaceted performance talents and business acumen into a degree of personal independence. Ella’s execution of roles typically assigned to men challenged entrenched Victorian notions of respectable female behavior. She defied the dominant tropes of women as weak and powerless.

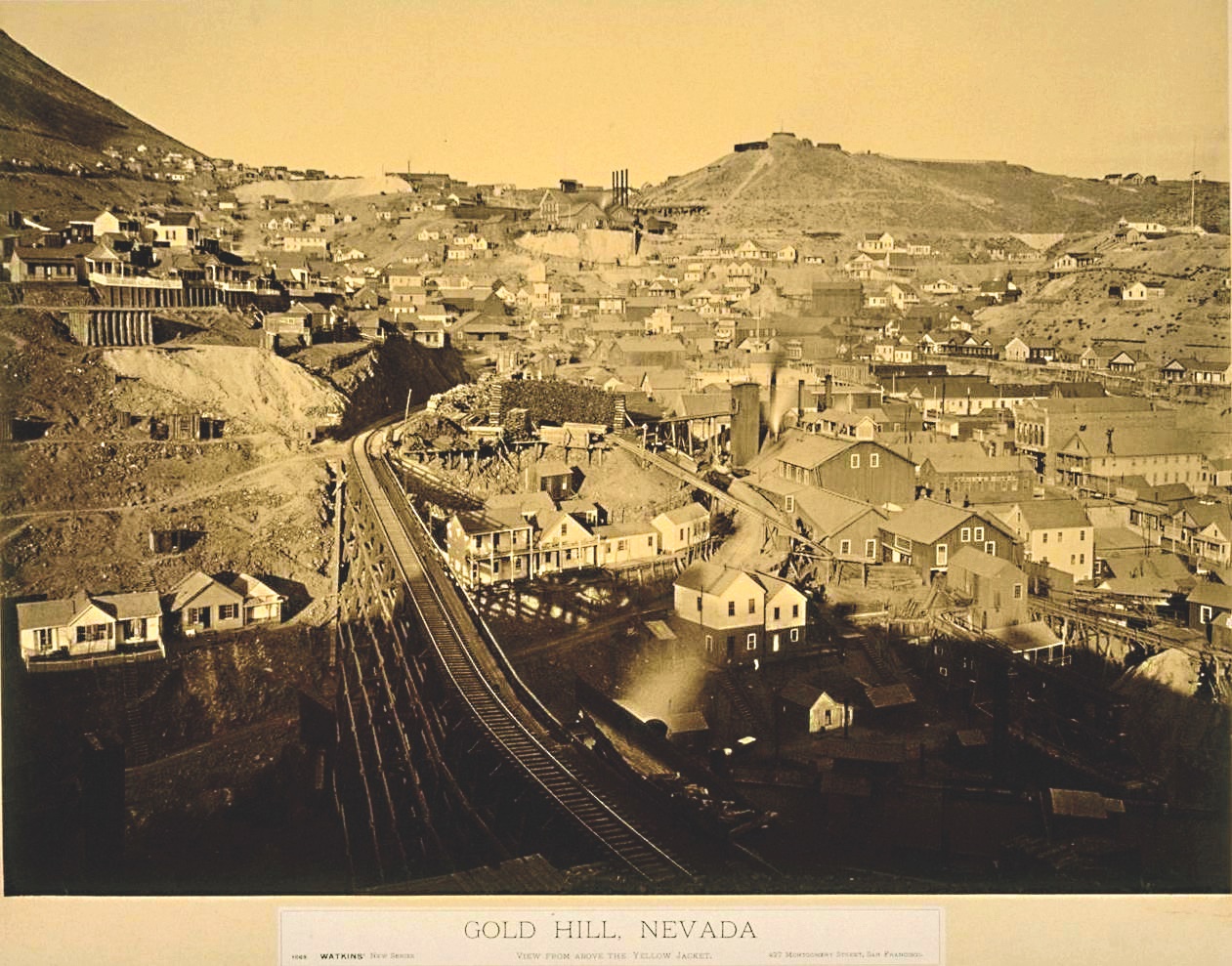

As a prelude to an 1868 engagement, Ella walked a tightrope stretched above the ground from the Piper’s Opera House balcony to a brick building on the corner of D and Union Streets in Virginia City, Nevada. The rope was about 30 or 40 feet above the ground, and the distance between the buildings forced a walk of about 160 feet. Her later career would see higher tightropes and longer processions, but this escapade was thrilling enough to draw a crowd of 500 spectators, many of whom retired to the theater to see her other theatricals. She walked from the Opera House and back in the moonlight enhanced by a bonfire in the middle of the street and a red fire burning at each end of the rope. To a star-struck newspaperman, she was a beautiful sight in a short frock, tights and trunks, carrying a balancing pole. That night Ella appeared in the farce afterpiece of Never Send Your Wife to Carson. In a simple plotline, the wife returns to find her husband in bed with another woman—slapstick comedy ensued.

In later shows Ella walked a tightrope inside the theater strung the entire length to the back of the stage. This type of spectacle titillated Victorian audiences with achievements believed unattainable by women. A high degree of self-discipline, practice and skill underlay Ella’s professional life.

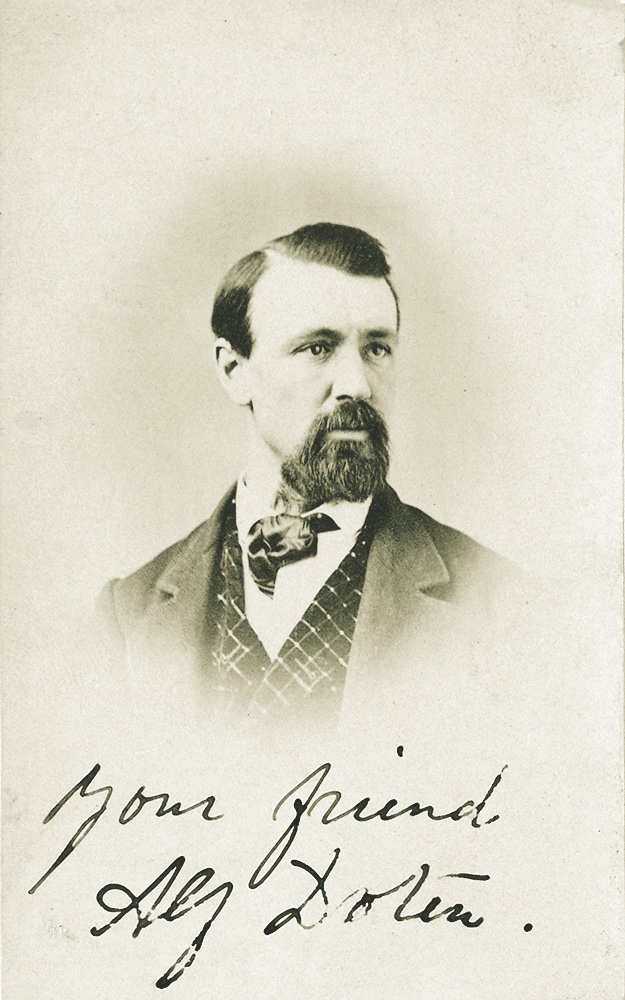

Women in Ella’s profession, one which relied on showing their bodies as commercial commodities, drew unsolicited attention from prospective suitors. While in Virginia City, Ella attracted the attention of bachelor newspaperman Alf Doten who met her backstage for a pleasant chat after her first show. The quintessential diarist, Doten came West with the California Gold Rush, documenting his exceptional experiences in dozens of finely detailed journals now in the University of Nevada, Reno Library’s Special Collections.

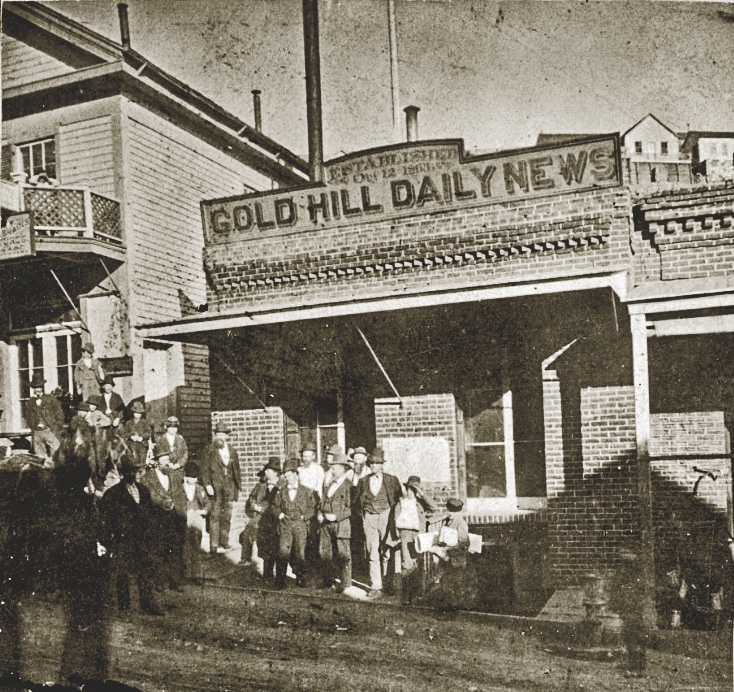

Doten’s diary entries recount his failed attempts to court Ms. La Rue during her months-long sojourn in the mining town in late 1868. Doten was seldom at home in the evenings, visiting La Rue at 6 p.m. in her room and then returning to the Opera House to witness her shows. Doten presented Ella with copies of the good notices of her performance that he had written for the Gold Hill News. He visited her room on several occasions but was rarely alone with her. On most occasions, Ella outmaneuvered Doten by having fellow minstrel performer Charley Rhoades with her for their get-togethers. On one occasion she was not available.

Doten brought his banjo with him to their meetings, but carelessly left it in her room on Christmas Day. He returned with a harmonica and later a flute, but the unflappable Rhoades became the musical partner in Doten’s improvised jam sessions in Ella’s room. His attraction to the star resounded in newspaper reports that Ella would play Koket, the Man Catcher, in the Happy Man skit. “She is handsome enough to attract almost any man to ineffable happiness or exquisite misery,” Doten opined to the News, perhaps while he was in the throes of exquisite misery.

The newspaperman was smitten with the star, not an unusual turn of events for women who performed on stage. The burlesque performances switched from Mazeppa to Black Crook, and Ella proffered a banjo lesson for Doten, but dashed his hope of a relationship. Her holiday pastime of banjo practice paints a rather dull picture of a dedicated performer, and although she recognized his interest in her, she balanced his ardor with the presence of other people so that he had few opportunities to become emboldened. As Ella La Rue dropped her clothes and got packed off on a “Chinaman’s jackass” in her Mazeppa burlesque, the News claimed she “displayed ravishing ‘shape’ enough to gratify the eyes of the greediest in that respect.” The comment says more about the critic’s greed than about the performance. Doten sent his last review with a letter to Miss La Rue after her departure from Nevada. She reciprocated by sending him three photos of herself through the intermediary, Charley Rhoades. Doten subsequently wrote to her, but painfully, did not receive an answer.

From Ella’s story may be drawn inferences about the success of sexualized variety show women who demonstrated an advanced sense of self-preservation offstage, while demonstrating a woman’s power to disrupt traditional hierarchies onstage. Ella was a professional whose somewhat boring life of practicing the banjo—she was considered on a par with the infamous Lotta Crabtree on the instrument—underscores her personal commitment to the performing life. La Rue also took the place of the leading minstrel performer and became the minstrel show’s “end man” when he resigned, arguing for her talents in quick-thinking, conundrums and the repartee of the traditionally male minstrel character. Her talents were significant, and she challenged the notion of the correct place for women in the social strata of the Victorian world. Where other women may have found the option of marriage to a man a salvation from the uncertainties of wage labor, professional performing women could avoid men intent on self-serving temporary liaisons. The Gold Hill Daily News theater critic lamented the loss of Ella La Rue: “She will be missed considerably by the patrons of the Opera House. She has gone from their gaze like a beautiful dream; they may never see her like again.” Indeed, during a long career she never returned to Virginia City to perform. Ella’s gender-bending foray into tightrope walking, cross-dressing and minstrelsy served her throughout the century, and infused the national debate of a woman’s proper place in society.

Ella was witty and intelligent, traits that served her well in the Wild West. She thwarted a stagecoach robbery near Deadwood, South Dakota, in 1877 by securing her earnings of 500 dollars into a coiled hairpiece and leaving only three dollars in her skirt pocket. The stagecoach robbers took the paltry sum and missed the money hiding in her hair. Newspapers had a field day with the escapade and hinted that the robbers should have searched the star entirely, perhaps focusing on the stripes in her stockings as a possible hiding place, a titillating reminder of the star’s sexuality.

A few years later, the Deadwood newspaper praised her talents: “Ella La Rue is a big card. She is perhaps the most versatile lady west of the Mississippi. She plays the cornet, the bones, dances a jig, sings well and talks like a yellow covered novel. Fact is, she is an artist in her profession.”

Triumph and Tragedy

In contrast to La Rue, variety star Fanny Hanks, known for clog dancing and her performance of the epic poem Sheridan’s Ride with a live horse on stage, died in abject poverty in an alms house. Although Ella and Fanny had appeared together in Chicago in 1867 in a short-lived variety show from San Francisco’s Theater Comique, Fanny performed mainly in the far West, where she reportedly made 700 dollars a week during her best years. Her marriage to a melodeon theater manager resulted in extreme domestic brawls. Her obituary hinted at retribution for her husband’s actions by audience members who took the law into their own hands and punished him severely for beating Fanny.

Another woman of the variety theater, Kitty O’Neil, found the West too wild after less than four years there. She settled permanently on the Eastern seaboard after interior tours and stardom in some of San Francisco’s Barbary Coast saloons. O’Neil, as Kitty From Cork, played Piper’s Opera House in November 1867, and a fight with another actress over earrings forced her to leave the area in a huff after her husband had been slipped a cathartic. The San Francisco Chronicle labeled Kitty a true talent whose genuine Irish brogue carried ineffable sweetness, although she was jailed on one occasion after a fight with a fellow minstrel performer. She played San Francisco’s notorious Bella Union, toured California with her own troupe, then stormed New York in 1871 as part of the San Francisco minstrels and remained a fixture there through the 1880s. For vaudeville audiences, Kitty wrote and performed her own composition, “No Irish Need Apply.”

Breaking All the Rules

Women of the variety stage rejected Victorian notions that tied so many women to their homes, families and volunteer organizations. Ideals of domesticity held that women would be corrupted should they leave the traditional roles of wife, mother and caregiver. The world was a dangerous place and women were moral souls created to stay within their spheres of influence as homebound wives. Variety women, as Ella La Rue demonstrated, could maintain a sense of distance from the “stage-door johnnies” who sought liaisons with them, and parlay their talents into a well-paid wage labor. The variety stage empowered women to develop talents that empowered them to pursue lives of meaningful employment. The fact that variety women showed their bodies in “visual trade,” means the larger society equated them with prostitution, but instead of selling their bodies to one man, they sold only their sexuality to many. The abilities of women in the variety theater enabled them to recast traditional gender values. Underscoring these talents was the not-insignificant willingness to travel without a male escort. Mobility during the Victorian era does not equate unilaterally to emancipation, however, performing women who did travel the West were better able to realize the success and affluence that could bring about emancipation.

The End of the Road

The Bismarck Tribune, in November 1879, reported that Ella La Rue snatched an orchestra leader from the local theater to take him with her to New York. The newspaper stated that Ella said, “she had wealth enough to take both him and her to New York.” This liaison ended badly, but Ella did eventually marry Samuel Murdy, a minstrel performer-turned-Leadville, Colorado silver miner, whom Ella met in the early 1880s. He became her wedded partner as well as theatrical cohort, and in 1885 they toured in a vaudeville company in which Ella usually received top billing. In the late 1880s Ella appeared briefly with her brother in trapeze artist programs, possibly signaling the end of her relationship with Murdy. The two divorced in 1890.

Minstrel performers rarely settled down until confronted with no other option, but the owner of the Park Theater in Great Falls, Montana, convinced Ella of the growth and real estate potential of Great Falls. She purchased land from him as early as 1888, and then settled into semiretirement there for the last 28 years of her life. Even in retirement Ella was something of a novelty to the folks of Great Falls, where she achieved local notoriety for her frequent real estate purchases. Her wealth and generosity were extensive; she bought farms for her parents and brother. In 1920 she purchased a winter home in southern California where she died leaving an estate of over 10,000 dollars—its relative worth in today’s money in the hundreds of thousands—to family and friends. Ella saved her money, invested in real estate and lived her retirement years in prosperity—a testament to her many talents.