— Courtesy Gates Frontiers Fund Wyoming Collection within Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress—

They came from Texas—and not because they’d heard that Chugwater chili was better than anything you’d find in Terlingua.

They arrived in Cheyenne, Wyoming, from Paris, Texas—once home of cattleman John Chisum, who likewise knew a thing or two about range wars—to take part in what Wyoming historian T.A. Larson calls “the most notorious event in the history of Wyoming,” and what, more recently, Christopher Knowlton has labeled “the Watergate of Wyoming.”

Yes, the Johnson County War of April 1892 remains a blight on Wyoming—and the American judicial system—but think about it. Would we have ever heard the words, “When you call me that, smile,” or “Shane, come back,” had it not been for this bloody feud?

Besides, it’s an easy road trip to travel.

If you believe what the cattle barons claimed, rustlers were running rampant in Johnson County in the late 1800s, and the cattlemen had to stop it—even if it meant violating state law and becoming vigilantes.

— Charles D. Kirkland, Courtesy of Wyoming Stock Growers Association Records, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming —

Leaving Cheyenne

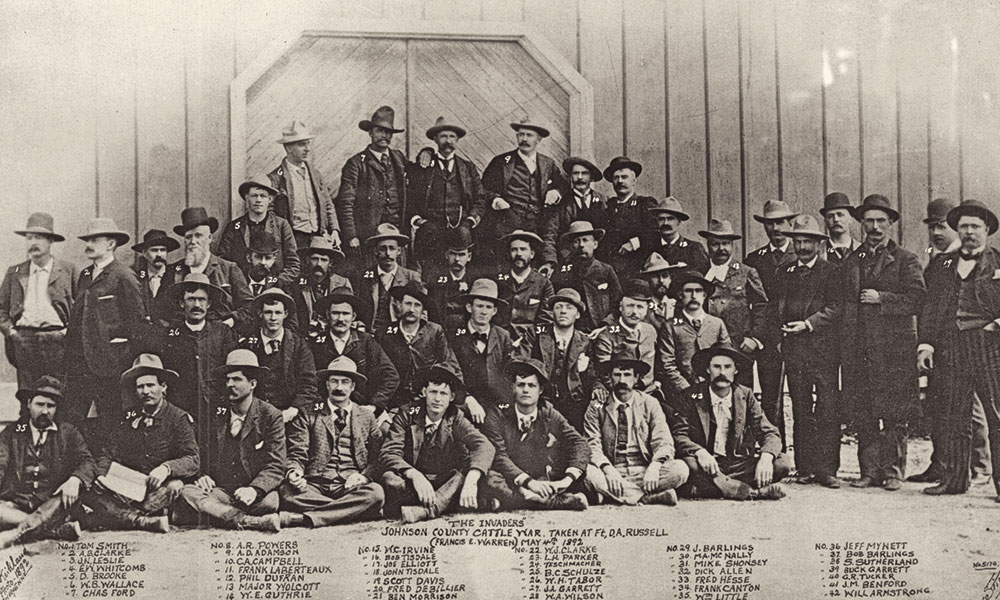

On April 5, 1892, a train arrived from Denver carrying 25 hard cases from Texas, recruited by stock detective Tom Smith—all top guns, if you believed the Texans. George Tucker, however, said this of the hired guns: “There were some good men, and some who were worse than no men at all.”

When the train arrived, roughly 25 men who had been attending the Wyoming Stock Growers Association began loading the train with horses, rifles, ammunition, wagons and food.

The train pulled out that evening, with some 75 animals and 52 men, who might have been animals themselves. They weren’t just planning on eliminating rustlers. As Knowlton puts it in his new book, Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West: “The plan was to get to Buffalo as fast as possible to kill the sheriff, his deputies, and every one of the Johnson County commissioners, thereby removing all county governance, which would give the invaders free rein to pursue other assassinations.”

— Courtesy Wyoming Stock Growers Association Records, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming —

Before you blame this disaster of a range war on Texans, keep in mind that the cattlemen had dispatched H.B. Ijams to recruit gunmen in Idaho. Apparently, Idaho gunmen didn’t want to play ball in Wyoming. Many of the horses came from Colorado. So did the ammunition, “enough…” John W. Davis quotes in Wyoming Range War: The Infamous Invasion of Johnson County, “to kill all the people in the state of Wyoming.” They brought along surgeon Charles Penrose, originally from Pennsylvania; three teamsters; and even two embedded journalists, Ed Towse of the Cheyenne Daily Leader and Sam T. Clover of the Chicago Herald.

Cheyenne was a cattle town and a railroad town and the state capital in 1892. It’s still a cattle town, railroad town and state capital. What’s more, it’s a town that preserves its Western heritage and legacy. Check out the whole town, but especially the Wyoming State Museum and Nelson Museum of the West.

An I-25 Mosey

Near Douglas, the telegraph lines were cut, which would hurt the invaders when the tables were turned and they couldn’t send word to the Cheyenne powers that the secret was out.

Around 4 a.m., the train stopped at Casper and the invaders unloaded. Had Lou Taubert Ranch Outfitters been around then, those Texans might have stopped in for some winter clothing, but the Taubert legacy didn’t get started until 1919 in Fort Laramie. It’s a great Western wear store in the heart of downtown. And don’t forget the Fort Caspar (“-ar,” “-er”…crazy Wyoming spelling!) Museum and National Trails Interpretive Center, even though neither plays a role in this story.

— All Photos Courtesy Wyoming Office of Tourism Unless Otherwise Noted —

The Texans also learned what April’s like in Wyoming. Horses stampeded. Wagons got stuck in mud from snowmelt. The invaders got out of Casper before the town woke up, but it started to snow.

The snowstorm turned into a blizzard. Cattleman Frank Wolcott got lost. Reporter Ed Towse learned that riding horseback is no fun when you have hemorrhoids.

Two miserable days later, the invaders reached the Tisdale Ranch on the South Fork of the Powder River. On April 8, Mike Shonsey brought word that a bunch of rustlers, including Nate Champion and Nick Ray (sometimes spelled Rae), were at the KC Ranch, 14 miles north on the river.

The invaders disputed whether they should wipe out Champion’s boys or go to attack “the fountainhead” that was Buffalo. In the end, they decided to hit the KC Ranch.

No Sunshine Band

There isn’t much to Kaycee these days, but the Hoofprints of the Past Museum and the Invasion Bar are well worth visiting. Of course, there wasn’t even a town in 1892.

Using public land like most outfits, big or small, Champion ran about 200 head of

cattle. Late on April 8, the invaders quietly surrounded the ranch. Two trappers, who had stopped to spend the night, were captured the next morning when they went out for water. When Ray stepped outside, he was shot down. Champion raced out, dragged Ray back inside, and the battle raged on.

The story has been told often in histories, novels and even that disaster of a movie Heaven’s Gate—still worth watching, just to say you’ve seen it.

Suffice it to say: Ray died, the invaders torched the cabin, and Champion, who had wounded a handful of invaders, signed off on the journal he kept during the hours-long gunfight: “Goodbye, boys, if I never see you again.” Champion was shot dead as he ran out of the burning cabin.

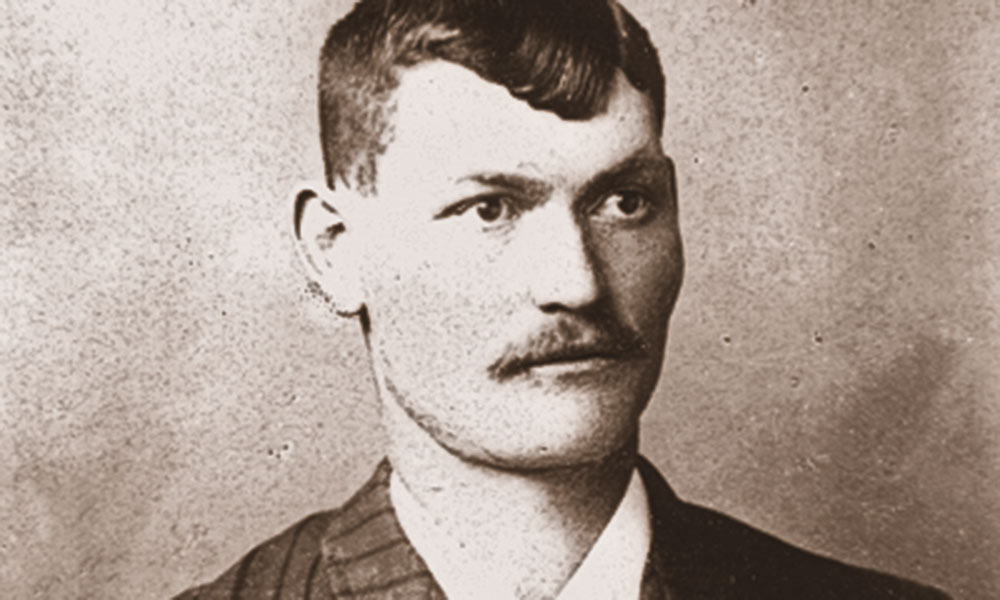

— Photo of Nate Champion Courtesy Johnson County Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum, Buffalo, WY —

That’s what the invaders wanted, of course. What they didn’t want was to be seen. But Jack Flagg, on horseback, and his stepson, Alonzo Taylor, driving a hay wagon, happened along. The invaders fired at them, but the witnesses escaped for Buffalo. Another local rancher also discovered what was happening. The alarm was sounded.

“That ends our raid,” Wolcott announced, and the invaders hurried for Fort McKinney, which became the Veterans’ Home of Wyoming in 1903, roughly three miles west of Buffalo.

The hunters became the hunted.

North Country

Buffalo sent out its posse. Volunteers from Sheridan joined the hunt. Northern Wyoming did not care for outsiders, and the invaders were about to find out just how Western things can get in this country.

Buffalo and Sheridan, both with a wide array of museums, historic sites, shops and scenery, certainly keep that heritage alive—especially at Buffalo’s Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum and Sheridan’s Bozeman Trail Gallery. In 1892, residents of both towns had little interest in keeping invaders alive.

Unable to reach the Army, the invaders holed up at the TA Ranch, still in operation today just outside of Buffalo, and learned what it’s like to be surrounded. They found shelter—the bullet holes remain visible in the ranch barn.

By April 11, some 200 and perhaps as many as 400 men surrounded the invaders. The posse built a log fort on wheels–dubbed a “go-devil” or “ark of safety”—and planned to use it to get close enough to dynamite the invaders out of hiding.

But soldiers arrived from Fort McKinney on April 13, and the invaders surrendered and returned to Cheyenne. How ironic that the cavalry rode to the rescue and saved the villains.

The invasion was over.

Justice, it can be argued, never came. Governor Amos Barber, in the cattlemen’s pocket, kept prosecutors at bay. Johnson County couldn’t afford the expenses.

Weeks of voir dire failed to seat a jury. The case was dismissed, the Texas gunmen went home and, as John H. Davis writes, “the criminal cases against the invaders came to their dishonorable end.”

Or as Knowlton puts it: “…the Cheyenne cattlemen…got away with murder.”

Johnny D. Boggs always stops at the Invasion Barin Kaycee because any place that serves cold beer and good hamburgers and has Gunsmoke on the TV is worth invading.