— All photos True West Archives —

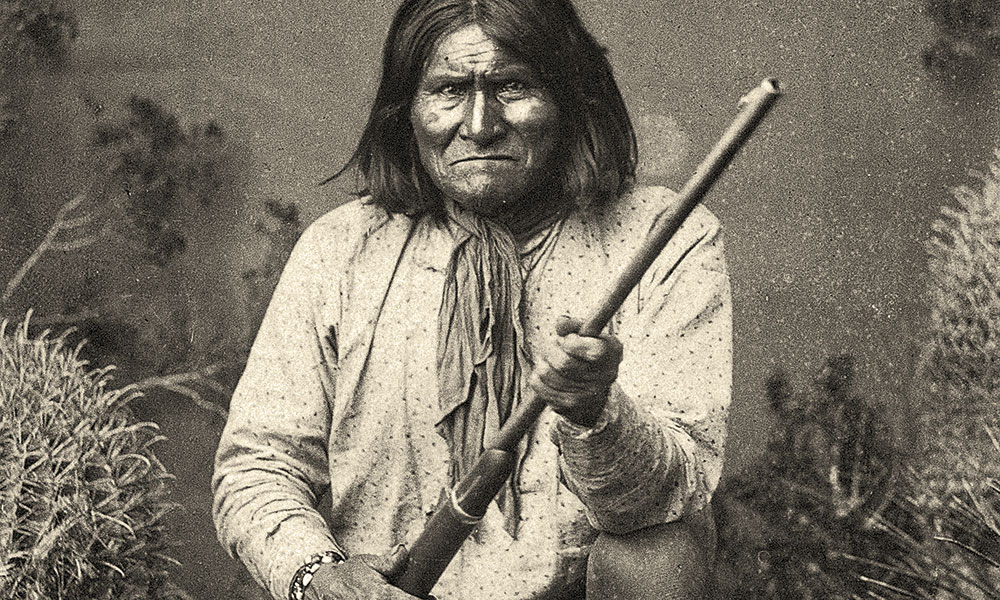

In 1886, when Geronimo ended the Apache Wars by surrendering his Bowie knife, his Winchester rifle and his scraggly band of renegade Apaches to the U.S. Army at Skeleton Canyon in Arizona Territory, Chatto, his former friend and eventual enemy, began serving 27 years in prison camp.

We all know about Geronimo. He became an American icon. But who was Chatto, and why don’t folks know about him?

Born into Cochise’s band of Chiricahuas in 1854, Chatto was only seven when Cochise declared total war on Americans after a deadly confrontation with them. Chatto rode with Cochise, his Uncle Mangas Coloradas and Geronimo while he was growing up and helped them turn southeast Arizona Territory into a burned-out wasteland.

He was a hardened 18 years old before Cochise signed the “Broken Arrow” peace treaty and settled down on a reservation—land carved from traditional stomping grounds near the Chiricahua Mountains. There, Chatto married and began a family. But the peace didn’t last long.

After Cochise died of natural causes in 1874, the U.S. government consolidated reservations, moving Cochise’s Chokonen band of Chiricahuas off their good reservation and onto a bad one: the hot, hated and unhealthy San Carlos.

Chatto refused to go.

He linked up with Geronimo, his elder of 25 years, and started a violent career as a Mexican raider.

Friend

Taking orders from Geronimo and his brother-in-law Juh, Chatto raided many Mexican villages, ranches and mines before he and Geronimo were captured in New Mexico Territory and taken in chains to the San Carlos reservation.

Both did okay on the reservation, despite food shortages due to rampant corruption and diseases that riddled the Apaches. A turning point came when the Army arrested a popular medicine man, Nockaydetklinne, at the Fort Apache reservation, inspiring a revolt, and then murdered that medicine man in 1881. Geronimo, Chatto and almost 300 San Carlos Apaches, fearing they would be next, ran back to Mexico to take up raiding once again.

During one of these raids, Chatto lost his family. In February 1883, the Mexican Army attacked the camp while the men were away, taking roughly 35 Apache women and children captive. Chatto’s wife, Ishchosen, nine-year-old Bedisclove and six-year-old Naboka were among the prisoners. The news devastated Chatto. He became obsessed with getting his family back.

Chatto first came into public prominence at this time. The Apaches needed more guns and ammunition to fight the Mexicans; Chatto would raid to get them.

Chatto and 21 Apaches hit nearly 40 targets and left no survivors. On March 28, 1883, between Silver City and Lordsburg in New Mexico Territory, they gunned down prominent Judge Hamilton McComas, bludgeoned his pretty wife and kidnapped his six-year-old son, Charley. Nobody heard from the boy again, which set off a national uproar, with demands to exterminate all Apaches.

General George Crook ran down the renegades in the heart of their hiding place in the rugged Sierra Madre Mountains. His troops and Apache scouts found Chatto’s camp and destroyed it. Stupefied that the Army had found them, most of the Apaches surrendered on the spot or promised to come in to the reservation as soon as they could round up their people.

By now, Chatto had realized that he could not retrieve his family through fighting, negotiations or bribery. He led 19 bedraggled tribesmen back to the reservation. Others, including Geronimo, soon followed. Chatto’s mentor was no longer Geronimo, but Gen. Crook.

Foe

Crook worked out a deal with Chatto. Chatto would serve as a top scout for the Army and work to end the Apache Wars, and Crook would attempt, diplomatically, to locate Chatto’s family and return them to the United States.

Chatto took his duties as a sergeant of the scouts serious. He helped the Army keep an eye on reservation Apaches and their excessive drinking of the native beer, tiswin. Geronimo and others began calling him a spy and a traitor.

The pair was diametrically opposed in how each one thought about the future. Geronimo believed all Apaches were going to die, so they may as well die free than on a reservation, while Chatto argued that how an Apache died did not matter as much as how he lived. His mantra became one of peace—go along to get along.

To get Chatto out of the way, for his next escape attempt, Geronimo ordered two cousins to assassinate Chatto and an Army lieutenant. But Geronimo’s hit men got cold feet.

After hearing about the foiled plans, Chatto went to work, in earnest, to bring down Geronimo. He led squads of scouts out into the wild, trying to cut off the renegades, during weeks and months, over deserts and mountains. He successfully found Chihuahua’s camp, wounded Chihuahua’s brother Ulzana and captured his family, along with one of Geronimo’s wives.

In retaliation, Ulzana raided Arizona Territory to kill Chatto and Geronimo raided Fort Apache to retrieve a wife. Their killings put the government under more pressure to remove all the Chiricahuas.

When Chief Chihuahua surrendered his small band in 1886, the government immediately shipped him and his people to prison at Florida’s Fort Marion. When Geronimo and Naiche also agreed to surrender, but then reneged, the military removed Crook and appointed hard-liner Gen. Nelson Miles, and then discharged Chatto and other scouts.

Geronimo continued to lead 5,000 soldiers on a merry chase all over the territory before he surrendered. Because Geronimo was still at war with the U.S., perhaps sending him and his followers to prison made some sense, but what happened to the peaceful Chatto was criminal.

The Double Cross

Extended an invitation by the government, a delegation of 10 reservation Apaches, including Chatto, visited the nation’s capital to discuss a possible move to another reservation away from Arizona Territory. Chatto and his people met with President Grover Cleveland and the Secretaries of War and Interior, and informed them they did not want to move homes and herds that they had worked hard to establish. The officials gave Chatto a silver friendship medal and a promise that he could return home and, if his tribe stayed at peace, they could live happily ever after. Then one of the biggest double crosses you can imagine took place.

When Chatto stepped off the train, he expected to be home, in Arizona Territory, but the government had rerouted the train to Florida. Chatto became a prisoner of war at Fort Marion. He and his delegation would remain prisoners for 27 years.

The government rounded up the rest of the peaceful reservation Chiricahuas. Geronimo’s and Naiche’s wives and children were sent to Fort Marion; the men were separated from their loved ones and sent to Fort Pickens. Fort Marion, with a capacity of 75, had almost 500 tribal Indians living (and dying) there.

The children were forced to attend Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where a high percentage of them died from tuberculosis, including Chatto’s son, Horace, and Geronimo’s son Chappo. Chatto married a 15-year-old girl, Helen, to prevent her from being sent to Carlisle. She remained with him for the rest of his life and gave him three sons.

Chatto was dead to the world at that point. His influence was revived via a stinging investigative report of prison conditions by the Indian Rights Association. Chatto became the star witness and an advocate and spokesman for his tribe. This, and pressure from Crook, led the government to try to improve the lives of the Apache prisoners, first by moving them to the infested Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama and eventually to Fort Sill in Oklahoma Territory.

Even though Chatto ultimately helped improve the lives of his people, renegade Apaches and their descendants ostracized Chatto for the rest of his life. Even worse, despite Crook’s promise, he never saw his wife Ishchosen and their children again.

In 1913, when the Chiricahuas were given a choice of remaining at Fort Sill or living on the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico Territory, Chatto, Helen, their sole-surviving son, Morris, and 136 others, no longer prisoners of war, chose Mescalero. Chatto prospered on 1,000 acres of land and remained a peace-loving leader. His descendants still live there.

A career broadcast journalist, John Sandifer is the author of Chatto’s Promise. He and his wife Kiki, live alternately in Seattle, Washington, and Buckeye, Arizona.