— Courtesy Eddie Basha Collection, Zelma Basha Salmeri Gallery of Western American and American Indian Art, Past winner of True West’s Best Western Art Gallery award —

In 1925, Kathryn Downing-Smith, the wife of one of Patrick Gass’s grandsons, wrote a letter to her niece Pearl about Gass. She offered keen insight into a man who, until his dying years, had been a soldier and teller of tall tales of his time with Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in the Rocky Mountain West.

“In height he [Gass] was medium, had gray-blue eyes, and dark brown hair. You will see the resemblance in their faces and you will recall mother’s stalky build, and she is very light on her feet,” she wrote.

“She must be like him in disposition too, for I have never heard her complain of her deafness and is even tempered, always making the best of hard circumstances, quiet, methodical, and persevering….

“He was sociable and liked company. Many people came to hear him tell of his experiences on the [Lewis and Clark] expedition. He always spoke with praise for Lewis and Clark…[and] he had a black cat which he named Sacagawea for the Indian woman who accompanied them.”

Gass lived the waning years of his life far from the wilds of the Rocky Mountains, in Wellsburg, West Virginia, which is situated roughly between Pittsburgh and Cleveland. He died there on April 2, 1870, just before his 100th birthday, far outliving any of the other Corps of Discovery members.

— Illustrated by Keith Rocco/ Courtesy National Park Service —

Sought for Corps of Discovery

Born on June 12, 1771, near Chambersburg, in central Pennsylvania, Gass later moved to the central part of the state with his family, serving in the local militia and working as a carpenter. In 1779, Gass enlisted in the regular Army and was stationed at Fort Kaskaskia in Illinois Territory. That post is where, in 1803, an equally young and ambitious man named Meriwether Lewis, with orders from U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, sought Gass for a most singular task: to join the celebrated Corps of Discovery.

The mission of the Corps was to chart a path to the Pacific Ocean in the newly-opened expanse of territory recently acquired by the U.S. from France in the Louisiana Purchase.

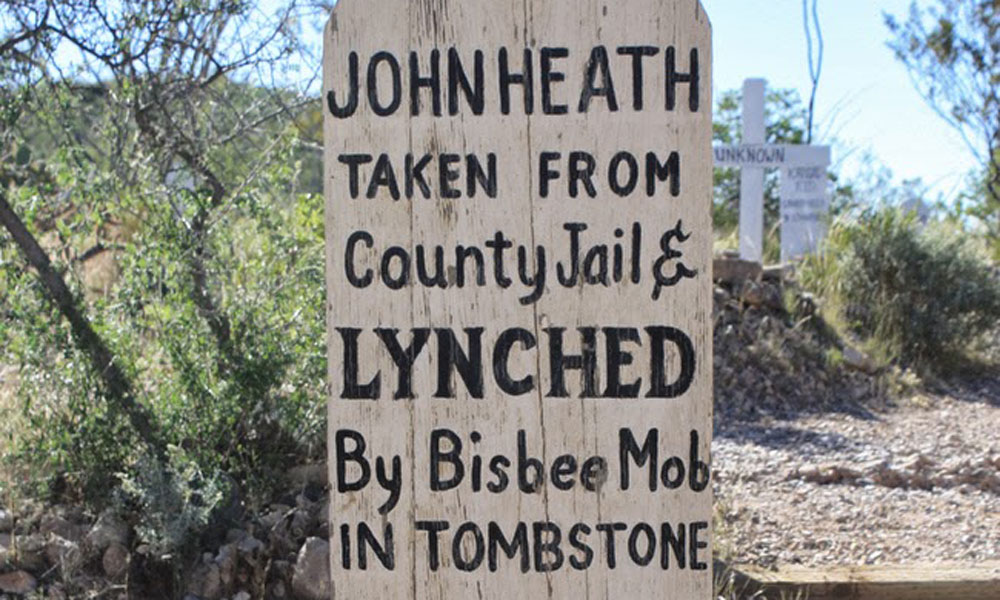

After the expedition left St. Louis, Missouri, and ascended the Missouri River, Sgt. Charles Floyd died in what is now known as Floyd’s Bluff in Sioux City, Iowa. The 22-year-old sergeant died on August 20, 1804, from a ruptured appendix.

Captain William Clark’s journal entry for that day read (typos left intact): “Floyd Died with a great deal of Composure…. We buried him on the top of the bluff. 1/2 Mile below [is] a Small river to which we Gave his name, He was buried with the Honors of War much lamented, a Seeder post with the Name Sgt. C. Floyd died here 20th of August 1804 was fixed at the head of his grave.

“This Man at all times gave us proofs of his firmness and Determined resolution to doe Service to his Countrey and honor to himself. after paying all the honor to our Decesed brother we camped in the Mouth of Floyd’s River about 30 yards wide, a butiful evening.”

That same night, the men elected Gass to serve as sergeant in Floyd’s place.

Floyd’s untimely passing was fortunately the only one of the entire 1804-05 expedition. Despite the sadness of the affair, all was not lost for the Corps. In Gass’s journals, he wrote of spending Christmas at Fort Mandan that year: “This evening we finished our fortification. Flour, dried apples, pepper and other articles were distributed in the different messes to enable them to celebrate Christmas in a proper and social manner.”

The completion of the fort was cause for celebration. On Christmas Day, Gass wrote: “Captain Clark then presented to each man a glass of brandy, and we hoisted the American flag in the garrison, and its first waving in fort Mandan was celebrated with another glass. The men cleared out one of the rooms and commenced dancing, which was continued in a jovial manner till 8 at night.”

The expedition built the fortified encampment along the Missouri River in present-day North Dakota. Gass’s skills as a carpenter were put to good use in constructing Fort Mandan.

Gass also oversaw the construction of winter quarters at Camp Dubois and Fort Clatsop. He hewed dugout canoes in Mandan, near White Bear Island in present-day Montana, and Canoe Camp, in Idaho, and constructed wagons to portage the canoes to the Great Falls in Montana Territory.

Not everything was a success. Gass also helped Lewis try to build his experimental iron frame boat near the Great Falls. Lewis had conceived of the idea back East, believing a lightweight and maneuverable boat would allow the expedition to make good time.

Once Lewis unpacked the boat, however, he realized the lack of pine trees meant he didn’t have a substance to make the pitch to seal the boat. Working obsessively, Lewis devised a makeshift formula of buffalo tallow, bees wax, charcoal and hides for the seal, but it proved unsuccessful.

“…to make any further experiments in our present situation seemed to me madness; the buffaloe had principally deserted us, and the season was now advancing fast,” wrote Lewis on July 9, 1805.

— Journal courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 4-5, 2008; Illustration courtesy Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois —

The Intrepid Fighter

After Gass returned to civilization in September 1806, he sought out and formed a partnership with David McKeehan, a Pittsburgh book and stationery store owner, to edit his expedition journals.

Gass, by his own admission, “never learned to read, write, and cipher till he had come of age.” Much of Gass’s journals paraphrase original field notes, which were destroyed during the initial publication.

Issued in 1807, Gass’s journal is important not only for its contents, but also for being the first published journal of the expedition, seven years before the first publication based on Lewis and Clark’s journals. The title page featured “Corps of Discovery,” and thus, Gass is credited for popularizing the name coined by the explorers.

Now middle-aged, Gass returned to military service and found himself stationed at the same fort in Illinois Territory he had been so eagerly recruited from in 1803. Gass saw service in the War of 1812. Two years later, he saw action at one of the war’s bloodiest battles in Niagara Falls, Canada, the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. During that battle, a falling and splintering tree caused Gass to lose one of his eyes.

Despite his injury, the intrepid fighter persisted. He wouldn’t stop until after the U.S. and Britain signed the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war.

In the years following the war, Gass found himself with little excitement and took to drinking and relaying to anyone who would listen stories of his days with Lewis and Clark in the Rocky Mountains.

He worked variously as a brewer, a ferryman and a carpenter. His respectable living was strengthened by the 1827 death of his father, who left Gass a sizable inheritance.

By 1829, Gass, now 58, had fallen in love with a 20-year-old woman. The two married in 1831, and, over the next 15 years, she bore him seven children. She tragically died of measles in 1846.

In 1860, he was kicked out of a local recruiting station for insisting on fighting in America’s Civil War. The chief complaint against Gass was not his fighting spirit, but his age, about 90 years old.

While Gass’s later years did not exhibit the excitement and adventurous spirit of his youth, he felt they were of equal importance, as reflected in Downing-Smith’s 1925 letter:

“Up to four years before his death when he became helpless, he walked weekly to Wellsburg to get the Wellsburg Herald for which he subscribed. At home he read the paper [and] cared for the small children. He was exceedingly fond of small children. The boys he held, one on either knee, and sang to them “Yankee Doodle,” queer Irish songs, and nonsense rhymes. This is one of them:

“A blue bird sat on a hickory limb;

He winked at me and I winked at him;

I up with my gun and broke his shin

And away the feathers flew!”

Erik J. Wright is an emergency management coordinator, in northeast Arkansas, an assistant editor for The Tombstone Epitaph newspaper and author of four books. He got his start in publishing at 16, when True West published his first article.