In 2017, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas towns are celebrating the sesquicentennial of the first cattle drives on the Chisholm Trail—from South Texas, across the Indian Territory (Oklahoma), to the new railhead in Abilene, Kansas—which launched the legendary era of the American cowboy, trail bosses, cowtowns and cattle barons. Since 1867, when those first cowboys survived the dangerous trail north to load their prized beeves onto the cattle cars of the Kansas & Pacific Railway, sending them east to slaughter and dinner tables, the story of the American cowboy has become as mythologized as Great Britain’s Arthurian Knights of the Round Table.

During the past three decades, the historiography of the West has produced hundreds of volumes of new and traditional Western American history, with numerous academic treatises on the real and imagined cowboy, but few, if any, monographs on the post-Civil War cattle industry for a broad, popular audience. Christopher Knowlton, after four decades of professional writing, advising and investing as an economist and Wall Street financier, has applied his lifelong passion for Western history—and career knowledge of American economic cycles and marketplaces—in writing the best one-volume history of the legendary era of the cowboy and cattle empires in 30 years. Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $29) redefines our understanding of the era beyond the traditional boundaries of the West, and as an ecnomic sector that helped drive America’s post-Civil War industrialization during the empirical globalization of marketplaces in the Victorian Era. Knowlton states succinctly in his Introduction, “No boom-bust cycle has had as lasting an impact on American society as the rise and fall of the cattle kingdom, and yet, oddly, this epic saga is largely forgotten today.”

– Courtesy North Dakota Historical Society –

Knowlton’s flowing prose style in Cattle Kingdom is enjoyable to read, as he expertly weaves the story of the post-Civil War cattle industry that entrepreneurially changed America economically, environmentally and industrially, with the personal stories of the men and women—famous and not so famous—from Theodore Roosevelt to Charles “Teddy Blue” Abbott—whose lives intersected between 1867 and 1887. From the trail drives and cowtowns, to the boardrooms and cowboys and cattle barons, railroaders and restaurateurs, Knowlton relates a sobering tale of the cowboys who worked the cattle, the range bosses who led the herds north from Texas, and the American and European cattle barons who built and lost empires worth tens of millions of dollars before most of it was lost in the Big Die-Up of 1886-’87. I particularly like Knowlton’s economic history, which explains “the larger forces that shaped and spurred the industrialization of agriculture. It looks at how global trade and flows of capital drove events every bit as much as the trail drivers themselves.”

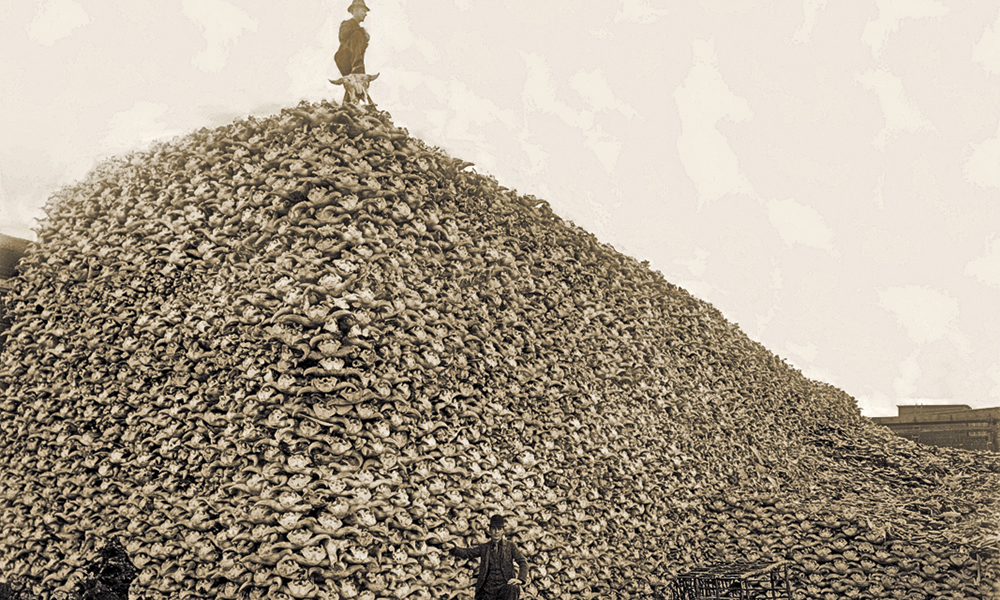

Knowlton, who currently makes his home in Jackson, Wyoming, has added a superb volume to the agricultural, cultural, economic and environmental historiography of cattle ranching and cowboy history in the American West. His early chapter on the destruction of the great American bison herds during the the rise of the open-range cattle empires—and the demise of the nomadic Plains Indian tribes culturally dependent on the buffalo—provides an allegorical foreshadowing to the rise and fall of the open-range cattle empires that is still relevant 150 years later. His detailed acknowledgments, insightful endnotes and thorough bibliography solidify Cattle Kingdom’s importance to the genre, and will be used as major resources for writers and students for many years. I especially appreciate his firsthand knowledge and zeal for the history of the West, its land and the people, its past and its present.

– Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library –

A very accomplished London economist, economics writer and New York Wall Street finance manager, Knowlton has told the national story of the post-Civil War range cattle era and provides the reader with a well-balanced interpretation of the highly romanticized era. He expertly juxtaposes the Western agricultural side of the story, and the men and women who lived, worked and died out West in the cattle industry, with the Midwestern and Eastern industrialization and economic side of the story. Most importantly, his conclusion provides context for today’s reader considering the market forces shaping the United States economy in the 21st century: “The open-range cattle era and its role in shaping America deserve to be more broadly known, if only as an instructive cautionary tale,” he warns.