– Courtesy Library of Congress –

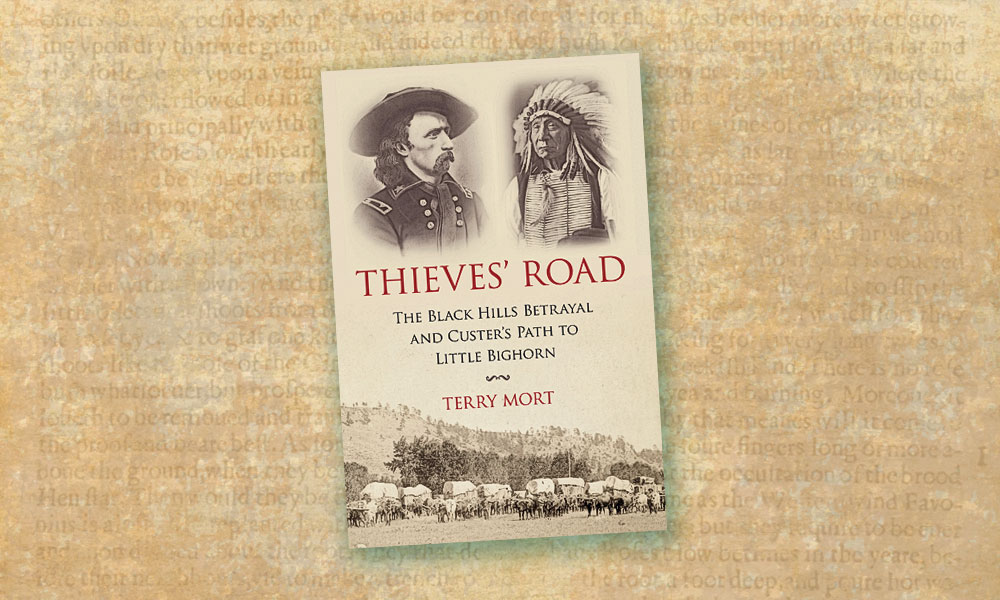

“GOLD!” proclaimed Dakota Territory’s Bismarck Tribune on the front page of its August 12, 1874, edition. The newspaper was exuberant about the discovery of gold by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s Black Hills expedition. It didn’t matter that the federal government recognized that the Black Hills belonged to the Lakota people, the rush was on.

After crossing the Cheyenne River in western South Dakota, a traveler heading westward across the prairie will spy low, dark mountains rising in the distance appearing as a landlocked island. The Lakota people call them Paha Sapa, Hills Black. The hills form a rough oval stretching north to south approximately 110 miles and east to west approximately 70 miles. The rugged mountains’ highest summit, Black Elk Peak, rises 7,244 feet and is one of the highest points east of the Rocky Mountains.

Black Hills geology is complex. The central granitic core is over two billion years old. Eighty million years ago an uplift began in the region. Imagine it as a massive boil that did not burst through the surface.

Over millions of years the outer sedimentary layers eroded exposing the inner granitic core alongside twisted, compressed metamorphic layers, and more recent sedimentary rocks flanking the Black Hills’ outer edges. Superhot subterranean fluids entered rock fissures depositing gold, silver and other metals as they cooled. The Black Hills is a rock hound’s paradise.

– All Images by Chad Coppess, Courtesy South Dakota Office of Tourism Unless Otherwise Noted –

Gold camps mushroomed throughout the Black Hills as prospectors explored every nook and cranny and sifted the gravel in every stream looking for the metal they dreamed would make them rich. The area is pockmarked with adits, shafts and tunnels. Trees were chopped down; overburden was piled high. Tailings ruined habitats, and some streams could no longer support life, as pollutants choked the life out of them. Through the efforts of the South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the U.S. Forest Service, other state and federal agencies, and concerned citizens and organizations, many damaged areas have been reclaimed, and streams have been restored to support healthy trout populations.

The Black Hills National Forest covers over one million acres of the hills. Traveling backroads through the Black Hills or hiking or biking along the many trails, one is bound to occasionally see cabin ruins or mine workings. Let’s explore the Black Hills area’s mining towns.

Gateway to the Black Hills

A good place to begin is Rapid City on the eastern slopes of the Black Hills. Nicknamed “The Gateway to the Black Hills,” it was established on February 25, 1876. It was not a mining town, but its founders were prospectors who thought they could make money by selling hay and necessities to miners. When Indians attacked, most of its residents fled, but a few hung on and Rapid City soon took root. In 1877, three suspected horse thieves were taken from jail and hanged. Most believe the youngest was innocent. He just happened to be with the wrong people at the wrong time. With a population of over 75,000 residents today, Rapid City is the second largest city in South Dakota. Tourism plays a major role in its diverse economy and it’s the manufacturing center for Black Hills gold jewelry with its distinctive grape leaf and cluster design. The Journey Museum and the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology Museum of Geology are two excellent places to view rocks, minerals and fossils from the Black Hills and learn about local geology and mining activities.

Gold Camp Fun

Twelve miles southwest on the Mount Rushmore Road, U.S. Highway 16, is Rockerville, where William Keeler discovered gold in December 1876, when he moved some discomforting rocks that prevented him from sleeping, only to find they were gold nuggets. The gold deposits were rich, but there was a lack of water. By 1880, a 17-mile flume was constructed from Spring Creek to Rockerville to wash the gold from the ground. The deposits of gold ran out and the flume fell into disuse. Portions of the flume can still be seen today. The town dwindled and for a time it was a tourist attraction. A few businesses are there today.

From Rockerville, continue on Highway 16 for five miles then turn on Highway 16A and drive two miles to Keystone. Named for the Keystone Mine, the town was founded in 1891. One nearby gold mine was named for the owner’s wife—The Holy Terror. Today, Keystone is a thriving tourist destination and gateway to Mount Rushmore. You can tour the 1892 Big Thunder Gold Mine and pan for gold.

For a fun 17-mile drive, take the Iron Mountain Road, U.S. Highway 16A, south, designed for scenic vistas of Mount Rushmore with tunnels, bridges, switchbacks and over 314 curves. Once the road enters Custer State Park it swings west toward the town of Custer. After passing Stockade Lake on the left, visit the reconstructed Gordon Stockade built on the original log fort site. The Gordon party occupied the site illegally in 1874 and was evicted by the Army the following year. A half mile to the west on Highway 16A along French Creek is where Horatio Ross and William McKay, two miners on Custer’s expedition, panning for gold on July 30, 1874, found enough gold flakes to be considered profitable, setting off the

gold rush. Highway 16A cuts through the expedition’s five-day campsite and you can camp where they did at either Wheels West Campground on the north side of the highway or at Custer’s Gulch Campground on the south side. Follow 16A and French Creek west for three miles to the town of Custer named after the lieutenant colonel.

Historic Custer and Hill City

Custer was established in mid-summer 1875 and was occupied off and on. The Army was tasked with removing all whites, but by November, the government looked the other way as prospectors invaded the Black Hills. Custer boomed until gold was found in the northern hills along Whitewood Creek. Today, Custer is a bustling town with a variety of tourist attractions. Visit the 1881 Custer County Courthouse Museum with its mining equipment display and personal items belonging to Custer.

From Custer, drive 14 miles north on U.S. Highway 385 to Hill City. The town was founded February 1876, but with the gold rush moving farther north to Whitewood Creek, it was abandoned except for one man and a dog. Tin mining restored life to Hill City in the 1880s. Today, Hill City is a thriving tourist mecca, its main street lined with shops and eateries. Take a relaxing, scenic ride on the Black Hills Central Railroad 1880 Train from Hill City to Keystone and back or examine the fossil displays at the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research.

Head northwest on Deerfield Road, continuing straight on the unpaved Mystic Road to Mystic and then the Rochford Road for 21 miles to Rochford. There’s not much left of Rochford. In 1878, the town had 500 residents, over 200 homes and business buildings supported by two gold mines with their stamp mills. The Stand-By Mill was a cool place to explore until it was torn down for fear someone might be injured. The mines closed, and as of the 2010 census, 12 people lived in town. Visit the Moonshine Gulch Saloon—nothing fancy but a fun place to stop for a cold beverage. A fire might be blazing in the wood-burning stove and a dog might wander through the door.

– Historic photo of the Stockade Courtesy The Beinecke Library, Yale University/the Gordon Stockade by Chad Coppess Courtesy the South Dakota Office of Tourism –

Deadwood and Lead

Head north on the Rochford Road, turn right on U.S. Highway Alt 14 heading north through the old mining towns of Central

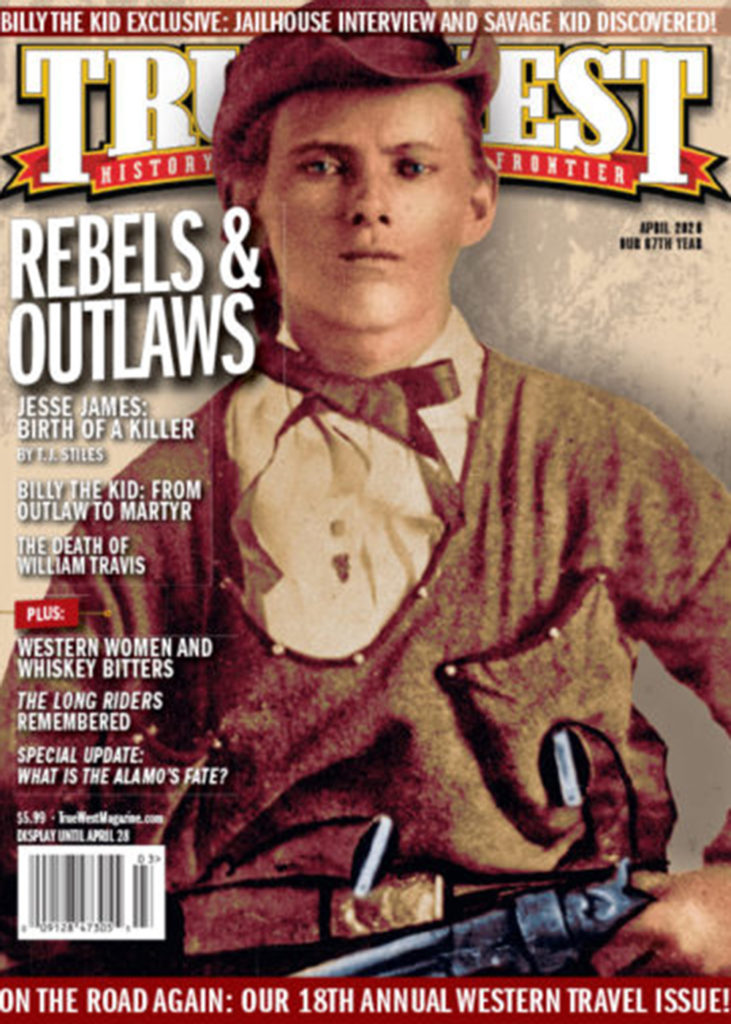

City and Gayville to Deadwood, a total of 22 miles. The Black Hills’ most notorious gold camp, Deadwood burst into existence in December 1875, when gold was discovered in Whitewood Creek. The rich placer discovery attracted thousands of miners—and those who mined the miners including characters such as Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, Al Swearingen and Seth Bullock. The town was destroyed through fire and flood, but the citizens always rebuilt it. Today, Deadwood is a vibrant tourist town. In 1989, South Dakota legalized Deadwood gambling with the stipulation that some proceeds be returned to the town for historic preservation. Investigate Deadwood by taking the Haunted History Walking Ghost Tour. Explore Deadwood’s historic facilities: Days of 76 Museum, Adams Museum and House, and the Homestake Adams Research and Cultural Center. Visit Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, Seth Bullock and other pioneers’ graves at Mount Moriah Cemetery. Explore Broken Boot Gold Mine and pan for gold.

From Deadwood, take Highway 385 two miles to Lead. In 1876, the Manuel brothers, Fred and Mose, found a rich vein of gold in their Homestake Mine and the town of Lead grew as mining entrepreneur George Hearst bought the mine and developed it into one of the world’s premier gold mines. The Homestake eventually became the largest producer in North America. At its height, Homestake reached over 8,000 feet deep with more than 370 miles of shafts and tunnels. It’s estimated the Homestake produced over 40 million ounces of gold. At an August 4, 2019, price of $1,441 per ounce that would equal over 457 billion dollars. The mine closed in 2002 but is now the Sanford Underground Research Facility where scientists conduct experiments for neutrinos and dark matter. Visit the Sanford Lab Homestake Visitor Center which explains the history of the mine and current activities. Peer into the enormous Open Cut, 1,250 feet deep, and take a surface tour of the mine facilities.

Enjoy a show or tour the Homestake Opera House built in 1914 by Phoebe Hearst. Visit the Black Hills Mining Museum and learn about mining techniques.

This is only a small nugget of what you can discover in your search for Black Hills gold history.

Bill Markley enjoys tromping through the Black Hills exploring obscure places. A Western Writers of America member, Bill’s latest book, Geronimo and Sitting Bull: Indian Leaders of the Legendary West, will be released in October 2020.