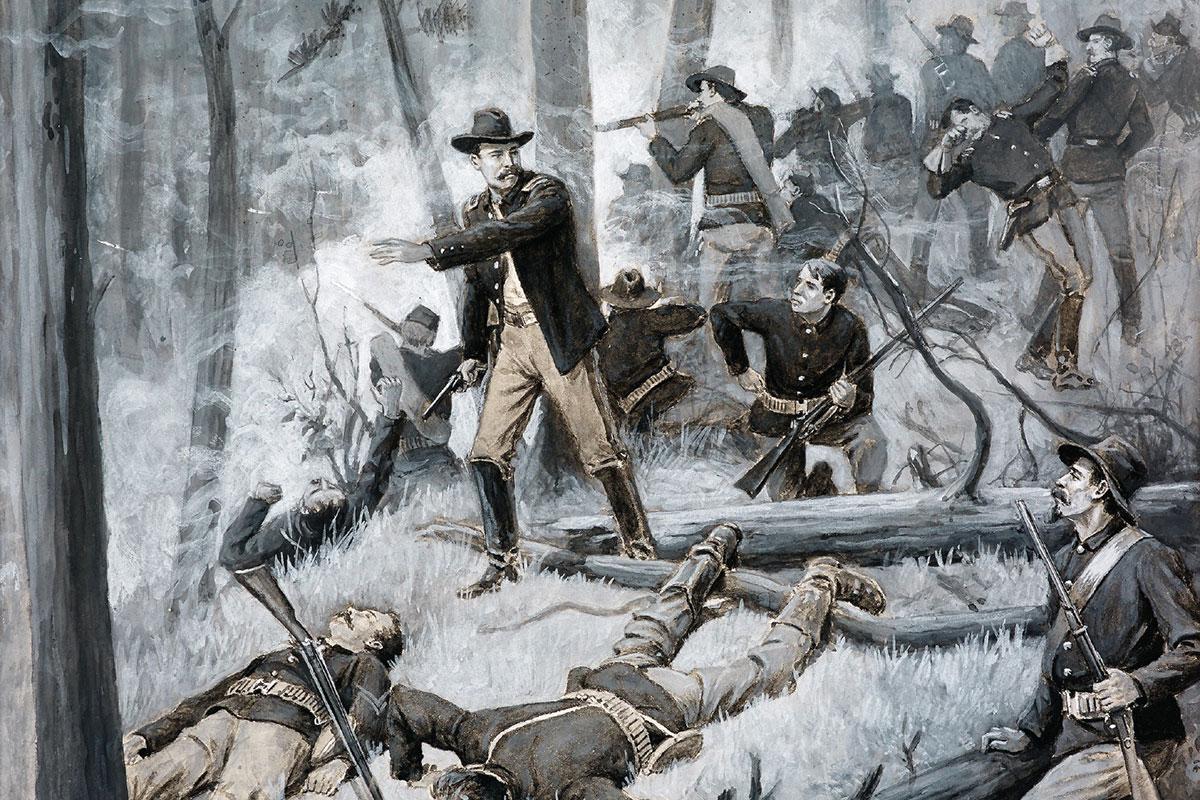

In 1882, Harpers Weekly, a very popular pictorial periodical of the Victorian era, purchased some sketches from a budding illustrator named Frederic Remington. Within a decade, the then-obscure picture maker/reporter was well on his way to international acclaim, eventually eclipsing others such as Charles Schreyvogel and an earlier rival for title of premier artist of the frontier Army, Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum.

Born on October 29, 1849, in Charleston, South Carolina, Zogbaum, as a youth, relocated with his family to a new and entirely different environment in New York City. By the early 1870s, he found himself in new surroundings again when he attended the University of Heidelberg (Remington briefly attended Yale, and Schreyvogel studied in Munich). Evidently, Zogbaum found his educational experience abroad less than satisfying. He decided to head home, but not before traveling on the Continent a bit. In fact, he made his way through other parts of today’s Germany, as well as a jaunt to Russia, and even managed to observe some of the action of the short-lived Franco-Prussian War.

These experiences may well have influenced him more than his formal training in the classroom. Once back in the United States, Zogbaum turned his hand to capturing military subjects using his facile pen for his first published picture featuring militiamen (akin to the National Guard) at Fort Hamilton, New York, in 1888. His debut appeared in the November 15, 1879, issue of Harper’s Weekly, nearly three years before Remington’s first entered the scene. Zogbaum’s three sketches launched a nearly half-century career, which ultimately included steady work as an illustrator and writer for ten magazines between 1885 and 1923, thereby squelching his family’s objections that studying art was a waste of time.

Soon after he achieved his first published success, Zogbaum headed across the Atlantic again. This time his destination was Paris. During his two “lonely” years in France, he became acquainted with the work of respected French artists Alphonse Marie de Neuville and Edouard Detaille, both widely known for their martial subject matter.

The die was cast. Zogbaum set out to follow in their footsteps, gathering material for an intended book with the working title of War Pictures in Time of Peace.

Eventually, he combined his renderings of European armies with a personal narrative that would be woven into a book released by Harper & Brothers in 1887 titled Horse, Foot, and Dragoons. This publication contrasted British, French and German forces with the American troops Zogbaum had accompanied in 1883 when he made his way to Montana. Once there, he rode with the regulars and may have been a bit taken aback by the informality of these frontiersmen in blue compared with their European counterparts. Nevertheless, he found his adventures in the West exhilarating.

Indeed, his sojourn to Big Sky Country provided the last ingredients for his pen and brush to complete the envisioned book while simultaneously introducing him to many new experiences, not the least of which was the fare of troops on the Western campaign. One of his passages captured a meal on the march, something he would not have found in Berlin, London, Paris or New York. Taking up camp chairs, hardtack boxes and whatever improvised seats the diners could muster, they gathered in the mess tent for a “bountiful breakfast” he described as:

“An antelope steak, some frizzled beef, trout (fresh caught), fried potatoes, coffee fit for the gods, with condensed milk in lieu of cream—everything smoking hot and in lavish profusion…. a pan full of the jolliest-looking biscuits, smoking through the cracks of their brown faces, just inviting to eat them…

[T]here is not a human being outside our command for miles and miles, with the exception, perhaps, of some ranging cowboys or prowling Indians.”

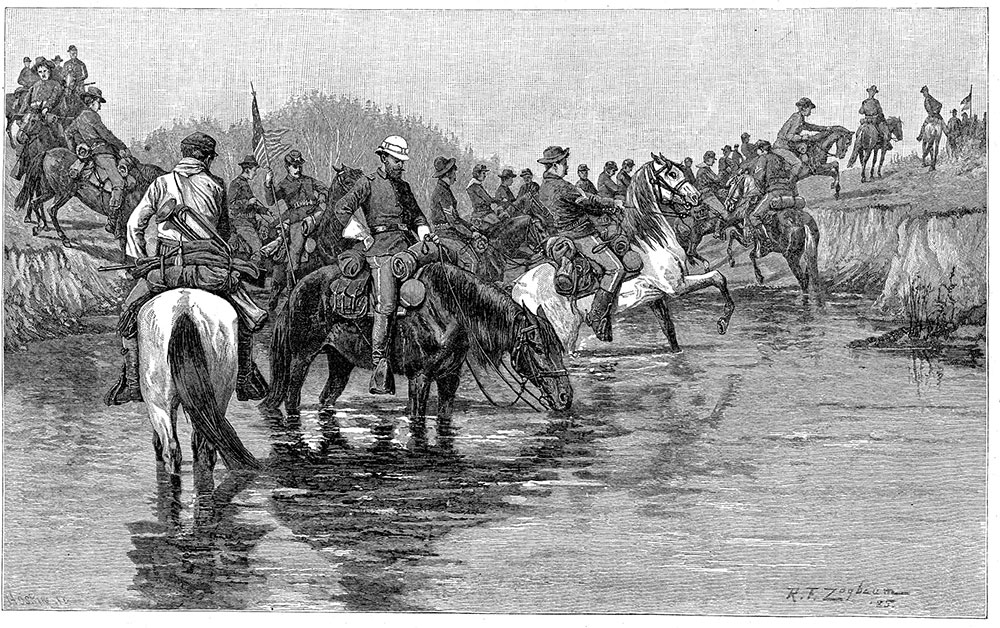

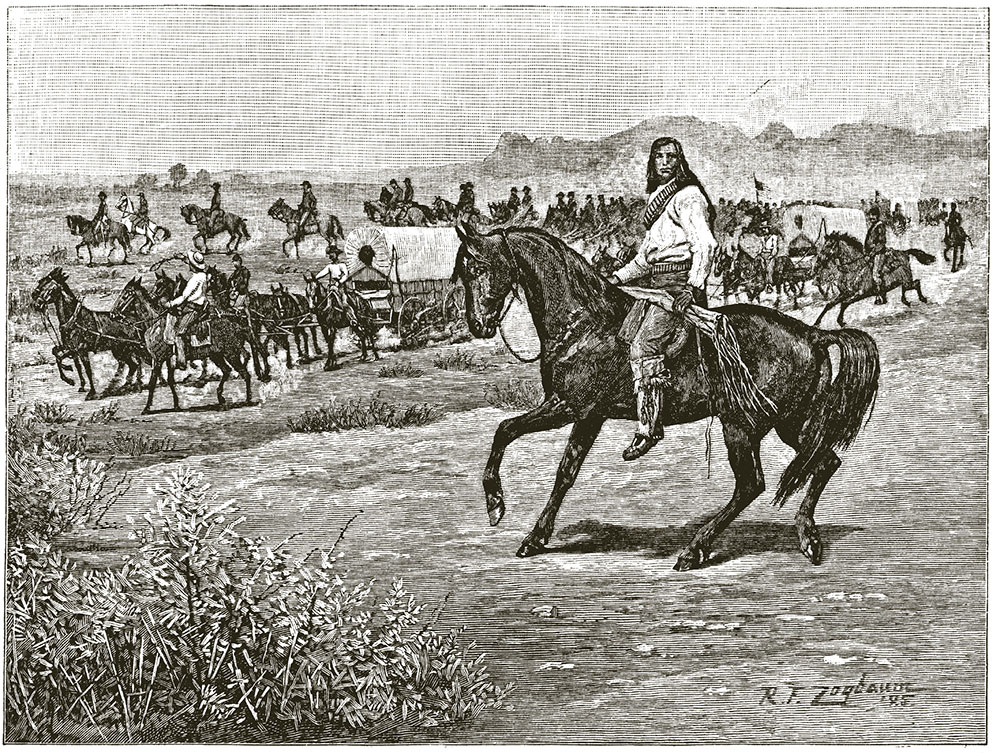

With the morning repast concluded, Zogbaum recorded what followed: “The camp presents a most animated scene. The tents already down…our bedding, neatly rolled and strapped…saddles are packed and placed upon our horses….” With that “Boots and Saddles” was sounded, while troopers stood near “their fluttering guidons, officers in front, awaiting the command to march.”

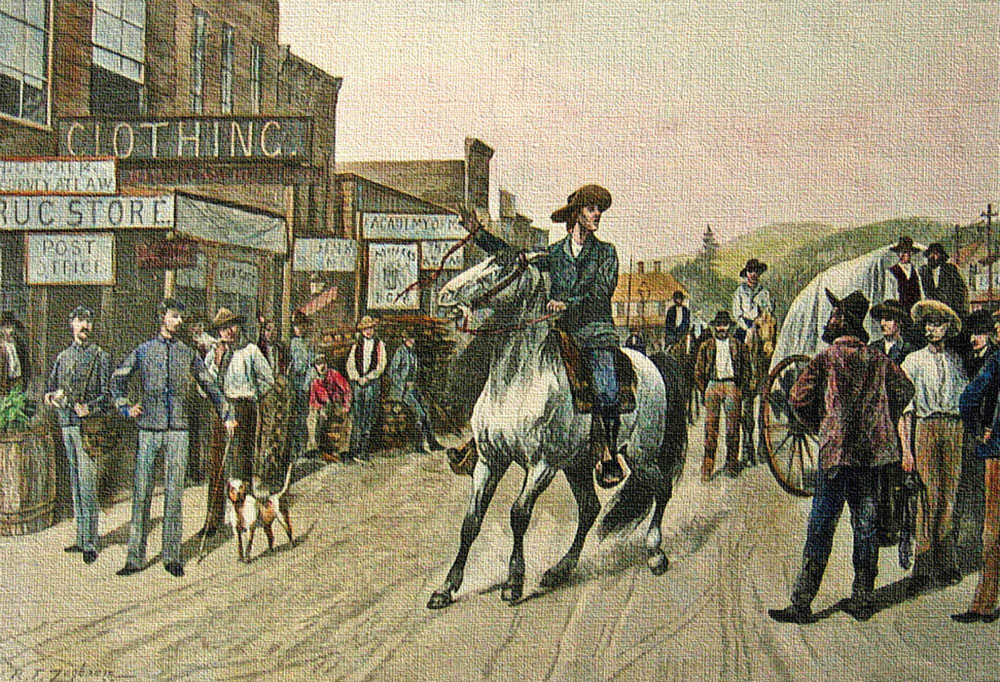

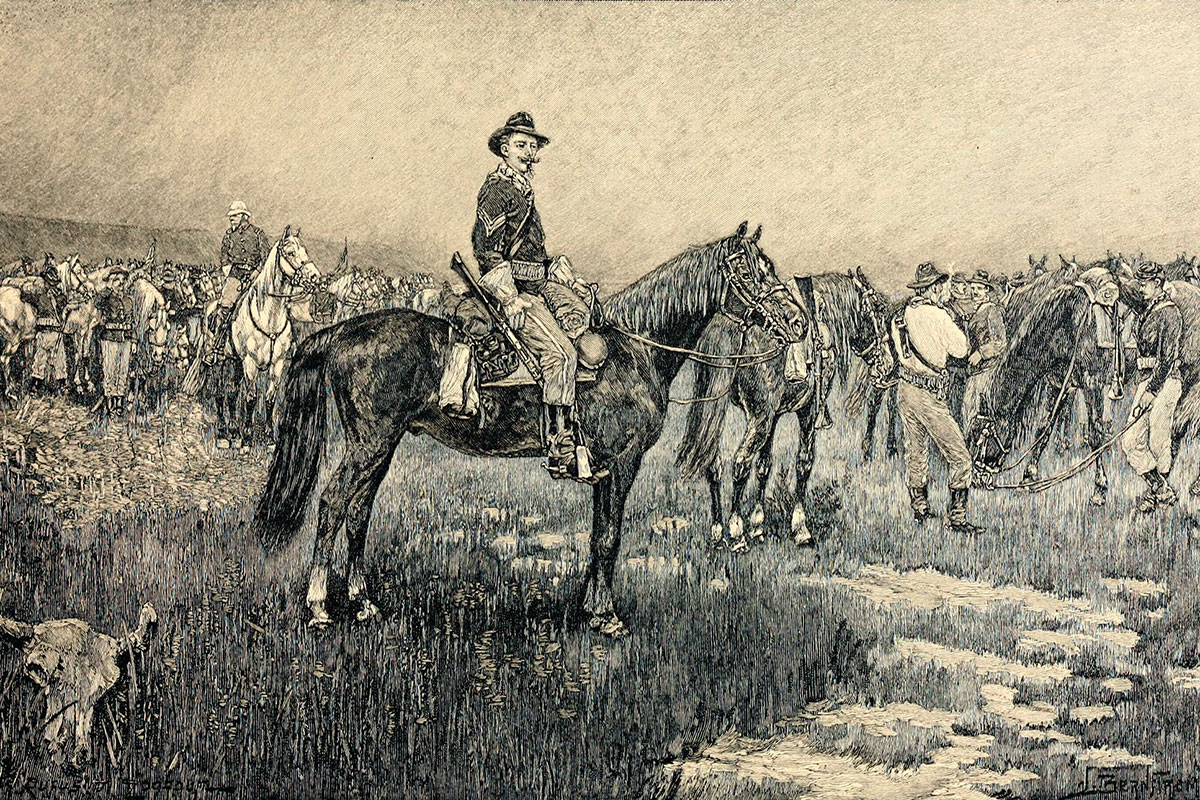

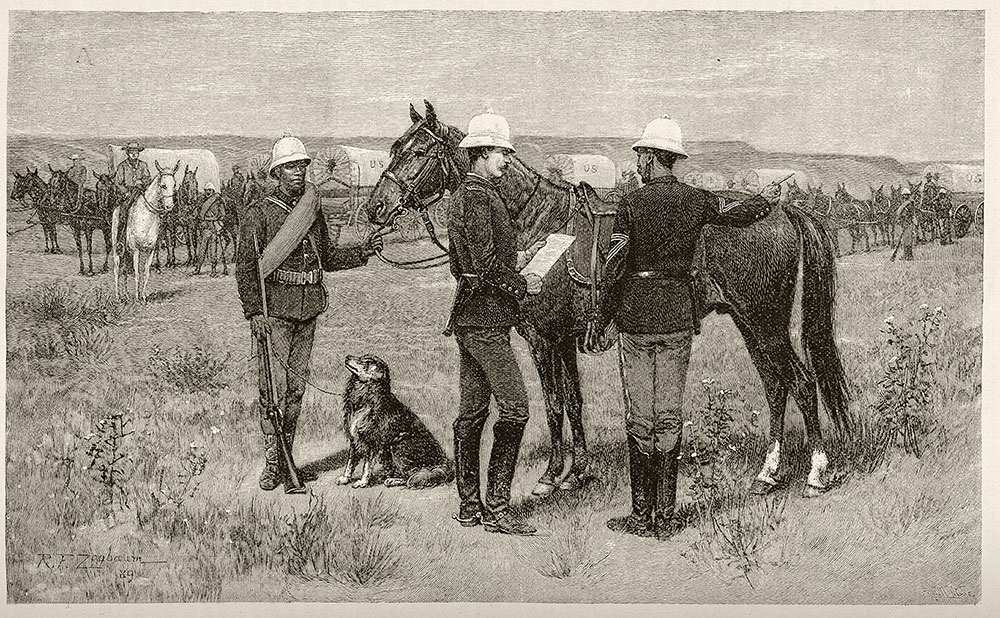

Ready to move out, the column was composed of men of “about middle height, sturdy and healthy, the majority of them unmistakably of American birth, but there is a strong sprinkling of Germans and Irishmen among them.” They were clad in a variety of regulation and non-regulation garb including “some with the more jaunty forage-cap, one man wears a civilian straw hat perched on the back of his head.”

Unlike Hollywood horse soldiers uniformly decked out in garish yellow bandanas, there are a few in assorted “gayly colored handkerchiefs knotted about their necks—one strapping fellow, whose whole countenance betrays his origin, wearing a bright green silk scarf, typical of the land of his birth.” Again, unlike on the silver screen, most of the officers “have put on their ‘best clothes’…. Most of them wear white sun-helmets,” but a few of them would have delighted John Ford in the “old regulation slouch hat” and indeed “one straight, fine-looking young gentlemen wears a great, broad-brimmed ‘cow-boy hat’ pulled down over his eyes.”

All this prompted Zogbaum to muse:

“We cannot help smiling as we think of what the astonishment of some of our European friends—the natty English artilleryman, the dashing French chasseur, or closely buttoned, precise German dragoon—would be, could they be dropped down here in front of the command, and how they would inwardly comment in no very favorable terms on the appearance of Uncle Sam troopers in the field.”

The sound of the trumpet returned Zogbaum from his speculation. He reported an “electric shock… traversed the assemblage, the scattered groups form in serried ranks. Another trumpet blast. Like one man, they rise into their saddles….” While enamored with Europe’s finest, he admitted:

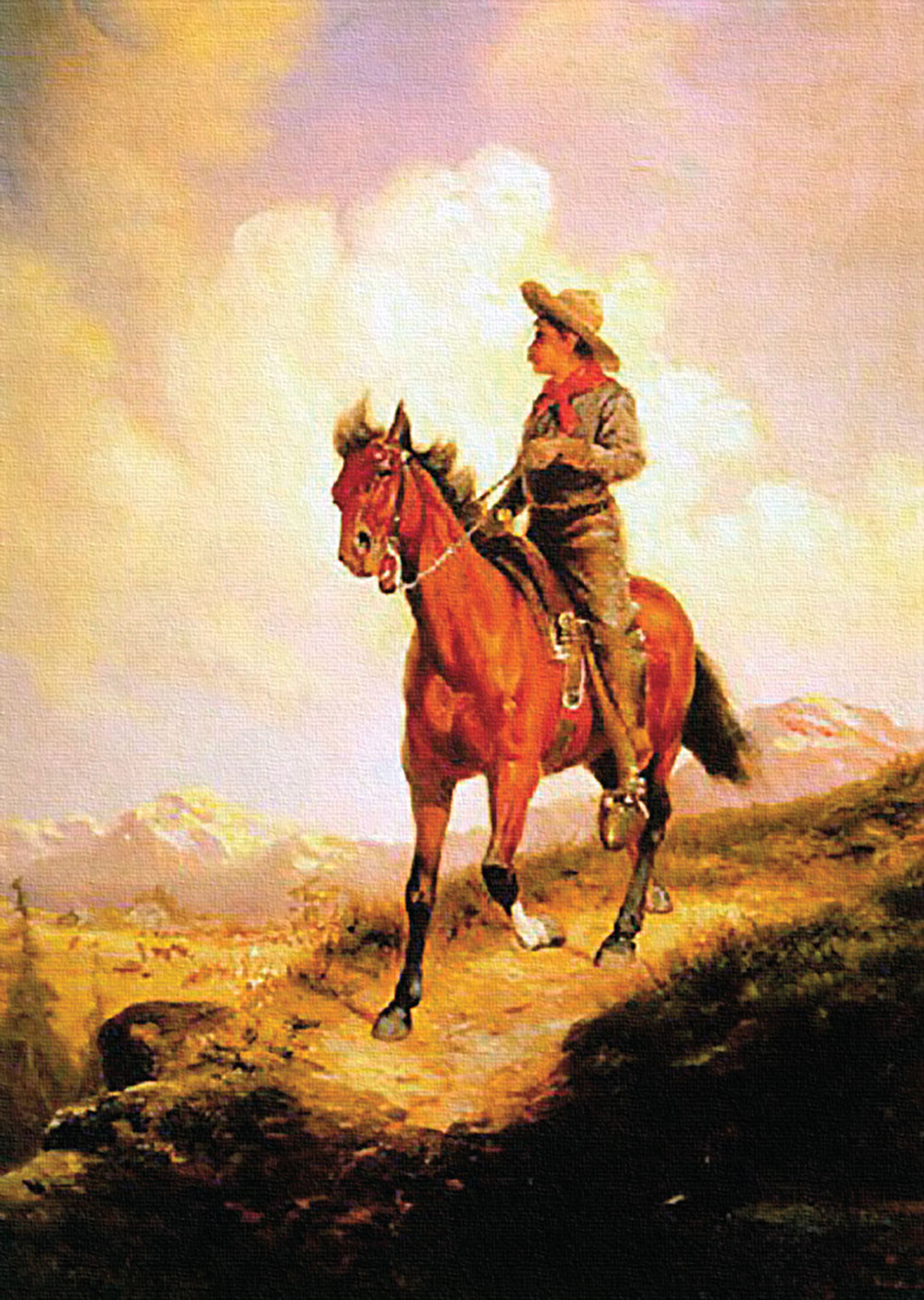

“In spite of their guerrilla like and careless look of the men, one cannot help but admire the soldierly ease and grace with which they sit in their saddles, ranks well aligned, shoulders squared, heads erect, eyes to the front, their harness and equipment shining in the sunlight, not a buckle or strap out of place, carbines clean, and swinging at their sides ready for immediate use, brass-shelled cartridges peeping from well-filled prairie belts, horses and riders moving with quiet and orderly precision that long training and constant habits of discipline alone can create. And the horses! Did you ever see better mounts? See that troop of sorrels that is just now passing! They have been in the field for weeks, and have passed through stream and canon, over plain and desert, through thick alkali dust and sticky mud, yet how their coats glisten, and how proudly they arch their necks and champ their bits, moving along at a rapid walk, guided by firm pressure of the practiced hands of their well-drilled riders! Though the uniforms are dim and weather beaten, though the harness and saddlery are of the simplest description, with little or no attempt at ornamentation, do not men and horses look ready for instant work…?”

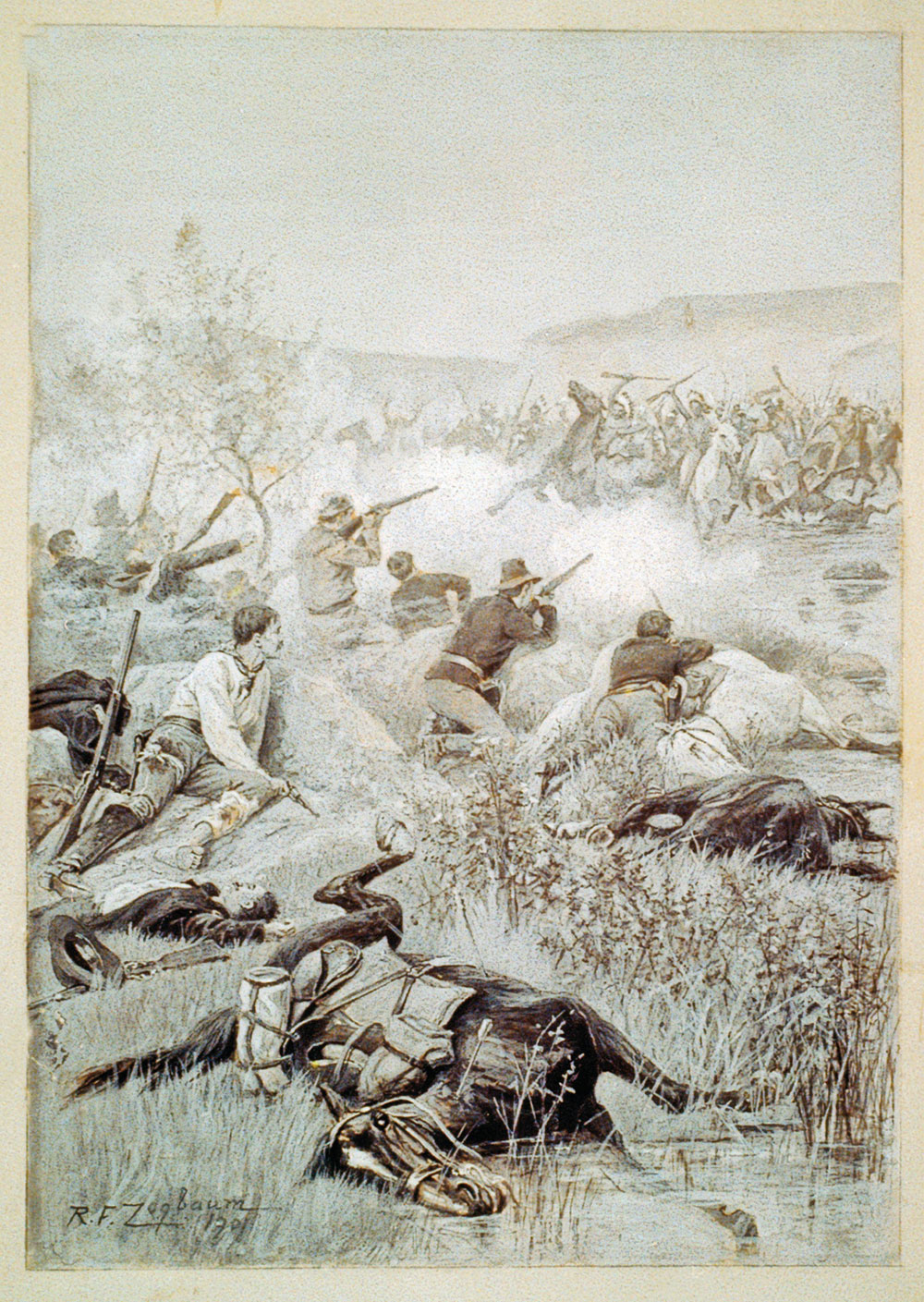

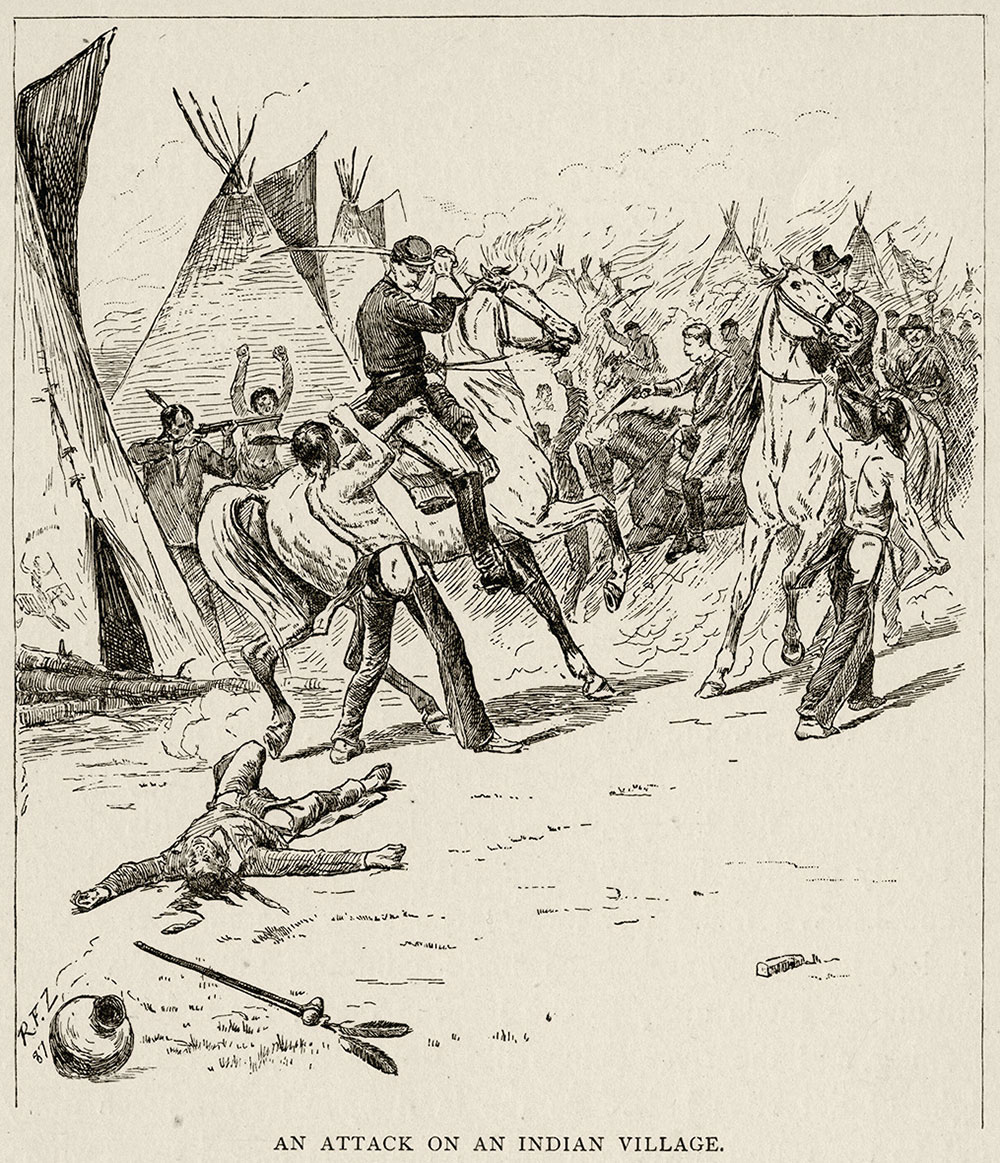

With prose equal to his painting and sketches, Zogbaum enthusiastically recorded the Army in the West and elsewhere, as well as producing frontier scenes. He went on to capture America’s overseas expansion during the War with Spain and depictions of the U.S. Navy on the high seas during the days of the “Great White Fleet.” He labored until the last two years of his productive life, and then quietly retired until his death on October 22, 1925. Regrettably, with his passing, his impressive body of work receded to be overshadowed by the works of others like Frederic Remington, who had continued on the trail Zogbaum blazed.

Military historian John Langellier’s current book, Scouting with the Buffalo Soldiers: Lieutenant Powhatan Clarke, Frederic Remington and the Tenth Cavalry in the Southwest, is scheduled for completion later this year.