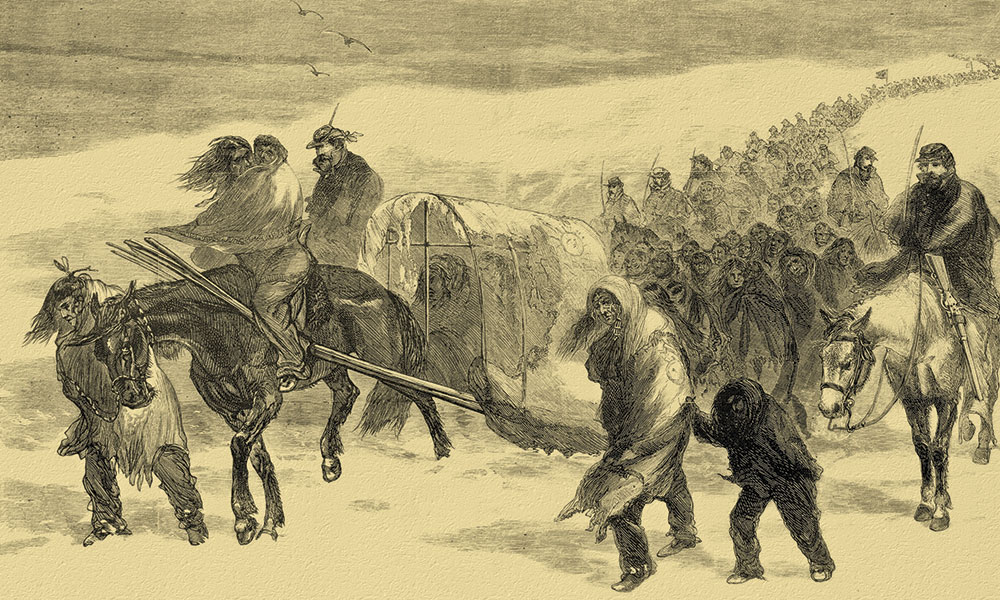

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Two months separated the 1868 clashes between the U.S. military and the Indians at Beecher Island and the Washita River.

One is known for heroism on both sides. The other has been called a “one-sided” battle or, more bluntly, a massacre.

The best place to start any Colorado history trip is in Denver, where the Denver Public Library’s collection is astounding and the History Colorado Center is state-of-the-art. But archives and museums don’t tell everything. To grasp the Southern Plains Indian Wars of 1868, travel south to Sand Creek, where four years earlier, on November 29, 1864, John Chivington led his Colorado militia against a peaceful force of Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians in south-eastern Colorado. The massacre fueled an off-and-on war that lasted roughly five years.

Which leads me to ask actor-playwright-historian Louis Kraft: Would Beecher Island or the Washita ever had to have happened if not for Sand Creek?

Yes, Kraft says, for these reasons:

“The Cheyennes and Arapahos occupied prime land between the Platte and the Arkansas rivers—thanks to the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty. When gold was discovered on Cheyenne and Arapaho land in 1858 and over 100,000 ’59ers invaded their reservation in 1859, the U.S. government made no attempt to stop them. After Denver City became a thriving metropolis—again on [Indian] land—nothing was said, and by the mid-1860s the reasons were becoming obvious. The white man wanted to build more towns, wanted to farm their land and began to cut roads for railroads that would slice through their land. All of this destroyed grass that their horse herds needed, destroyed trees and, at an alarming rate, frightened away or decimated the buffalo herds and other game that was necessary for their survival. Although never called a land grab, it was.”

— Courtesy Kansas Tourism —

To Beecher Island

In August 1868, Gen. Philip Sheridan ordered Maj. George Forsyth to lead 50 civilian scouts after Indians, who were attacking white travelers and Kansas Pacific Railroad workers. Lt. Frederick Beecher of the 3rd Infantry was assigned as second in command.

They traveled light. “A blanket apiece,” Forsyth recalled in his memoir, published 32 years later, “saddle and bridle, a lariat and picket-pin, a canteen, a haversack, butcher-knife, tin plate and tin cup. A Spencer repeating rifle (carrying six shots in the magazine, besides one in the barrel), a Colt’s revolver, army size, and 140 rounds of rifle and 30 rounds of revolver ammunition per man—this carried on the person.”

Sent to Fort Wallace (only the post cemetery remains, but the Fort Wallace Museum is excellent) in western Kansas, the scouts left on September 10 and followed an Indian trail northwest into present-day Colorado.

At dawn on September 17, the scouts found the Indians: all 600 (some say as many as 750) Cheyennes, Arapahos and Lakotas. Forsyth hurried his men to a sandbar in the middle of the Arikaree River.

Beecher was killed. So was the acting surgeon and two others, while many, including Forsyth, were wounded. They dug into the sand, hid behind dead horses, and fought for their lives.

On the Indian side, Cheyenne leader Roman Nose had skipped the first charges because he thought that if he fought on that day he would be killed. With the fighting going badly, others begged him to lead a charge. Roman Nose “could not resist the temptation,” Cheyenne George Bent wrote, “and went to his death.”

Says Kraft: “This was truly a horrific tragedy for the Cheyennes as [Roman Nose] had stood firm for keeping their land and their freedom at all costs.”

Still, the scouts were trapped on the island, their horses dead, and even after the Indians left—the battle lasted only two days—Forsyth’s men weren’t going anywhere. During the siege, a few scouts volunteered to try to make it to Fort Wallace—60 miles away—for help. Somehow, they all made it, and on September 25, black troopers commanded by Louis H. Carpenter arrived at Beecher Island, greeted by the rotting smell of the dead horses Forsyth’s scouts had been forced to eat.

“Buffalo Soldiers received the warmest reception,” historian Michael N. “Cowboy Mike” Searles says, “when they rode to the rescue of white soldiers in a tight spot.”

The scouts were glad to be off that island.

The island and a 1905 monument were washed away in a 1935 flood, and reaching Beecher Island and its newer monument (on higher ground) requires patience and a steady hand on county roads. The nearby (although not that close) Wray Museum also chronicles the battle.

Strategically, Beecher Island was insignificant, but George Custer called it “the greatest battle on the plains.” Historian John H. Monnett has noted that “the sensationalism it generated, indirectly led to an infusion of new troops into the Plains, culminating in the Washita campaign.”

Which brings us to the other side of bloody 1868.

To the Washita

As raids continued, Black Kettle, a Cheyenne who had survived the Sand Creek Massacre, met with Colonel William B. Hazen at Fort Cobb to discuss peace.

Black Kettle said: “I have always done my best to keep my young men quiet, but some will not listen, and since the fighting began I have not been able to keep them all at home. But we all want peace….”

Hazen said he wanted peace, too, but Hazen had no control over Sheridan, who, Hazen said, “has all the soldiers who are fighting the Arapahos and Cheyennes. Therefore, you must go back to your country, and if the soldiers come to fight, you must remember they are not from me, but from that great war chief, and with him you must make peace.”

Side note: After the Washita fight, Sheridan and Custer moved the command back to Fort Cobb. Nothing remains of the original fort (now on private property), but a stone marker is at the fairgrounds and a highway marker is on Oklahoma Highway 9, about 15 miles west of Anadarko, which is worth visiting, too.

— Johnny D. Boggs —

Sheridan wanted to hit the Indians during the winter. To do this, he had a supply camp established in present-day western Oklahoma. This became Camp (later Fort) Supply, but as historian Jerome A. Greene quotes one officer in Washita: The U.S. Army and the Southern Cheyennes, 1867-1869, the name didn’t quite fit: “While there

was a partial supply of everything, there was not an adequate supply of anything….”

Today the site, managed by the Friends of Historic Fort Supply, includes five original buildings, including the 1892 brick guardhouse.

From Camp Supply, Custer led the 7th Cavalry to his first major engagement against Indians. His scouts found an Indian trail on November 26—the day Black Kettle was back at his camp on the Washita River—and Custer’s troops followed it into the night. Custer divided his troops into four prongs and attacked at daybreak.

The attack would earn comparisons to Sand Creek, but historian Kraft notes a big difference: “Chivington…knew exactly who was in the Sand Creek village, and he knew that it would be easy pickings. Custer…had no clue what people were in the Washita village.”

Part of the battlefield is preserved at a National Historic Site just west of Cheyenne, Oklahoma. The film at the visitors’ center, Destiny at Dawn: Loss & Victory on the Washita, offers a good overview of what happened on that winter morning.

Osage scouts killed many women and children, said Ben Clark, one of Custer’s guides/scouts. Black Kettle and his wife were shot dead while trying to cross the Washita River. With a foot of snow on the ground, the troops drove the Indians, most of them barefoot and barely clothed, into the woods and ravines. The “real fighting,” one soldier recalled, “began when we attempted to dislodge them from ravines or ambush.”

“Here goes for a brevet or a coffin!” shouted Maj. Joel Elliott before leading a detachment of 17 men after some fleeing Indians. Elliott got his coffin. Two weeks later, the bodies of the entire command were found two miles from the village. Captain Frederick Benteen blamed Custer for abandoning those men and would make a career of criticizing and hating Custer that continued well after Custer’s death at the Little Big Horn in 1876.

Edward W. “Ned” Wynkoop was heading to Fort Cobb when he learned about the Washita, and resigned as Indian agent for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapahoe on November 29.

“As far as he was concerned, Custer’s actions were ‘wrong and disgraceful,’” Kraft says. “A view that most of those living on the borderlands disagreed with.”

Johnny D. Boggs warns tourists to watch out for fog when driving to Beecher Island during the summer.