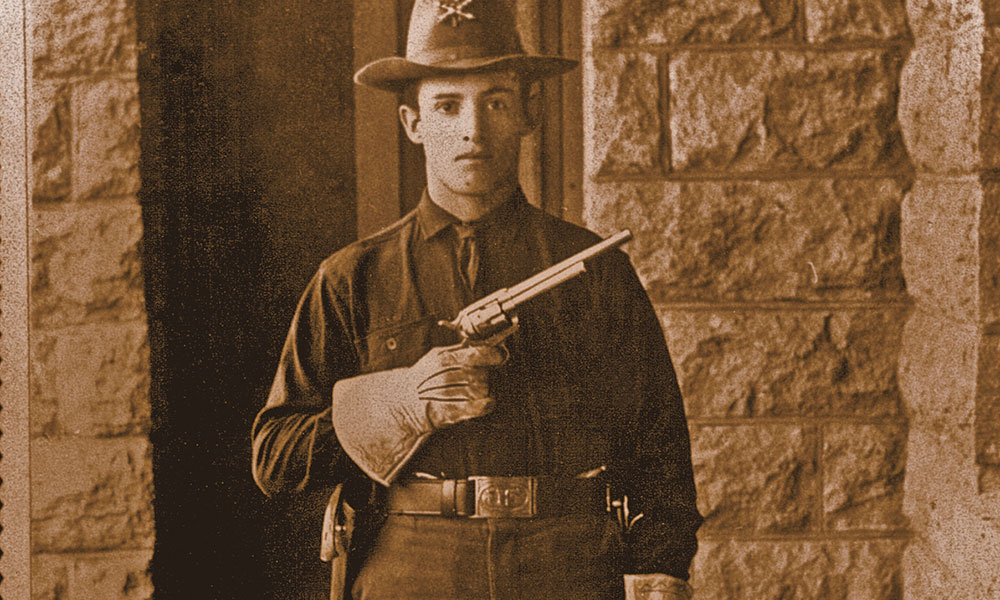

— Courtesy John Kopec —

Arms enthusiasts often ask which government-issue .45 revolver was the best during the Indian campaigns of the late 19th century—the 1873 Colt or the “1875” Schofield. While each had its advantages and drawbacks, the Colt saw the most use with 37,063 being issued from 1873 through 1893. About 8,285 Smith & Wesson Schofields—3,000 of the first model and approximately 5,285 of the second model—were contracted for the cavalry.

Nevertheless, the Schofield was considered by the 1874 military review board as “well suited to the military service.” Although both of these cavalry six-shooters received mixed reviews from the troops who used them, opinions were generally favorable for both. Let’s look at some of the differences of these martial sidearms.

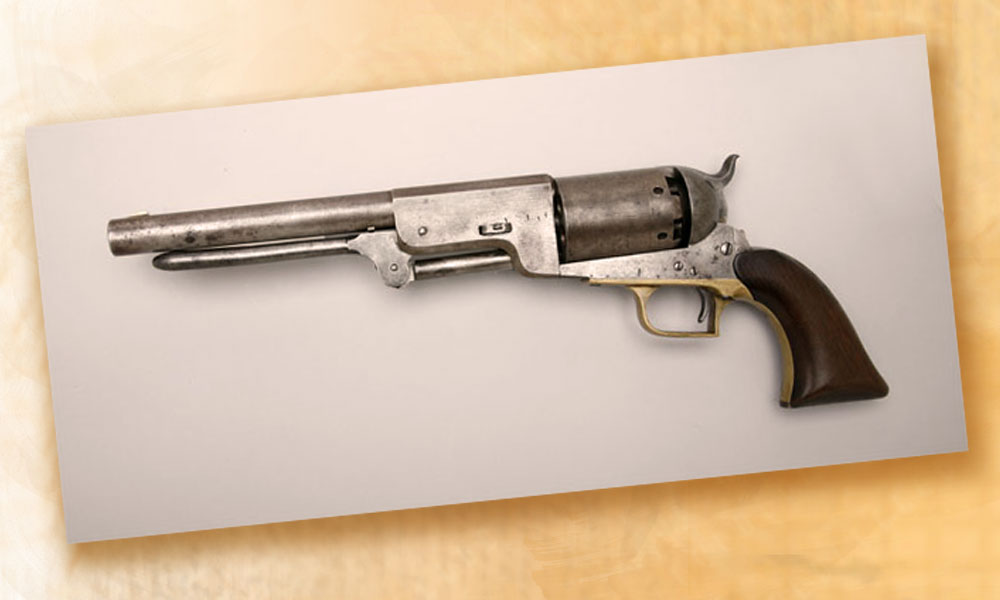

The solid-framed, more simplistic 1873 Colt Single Action Army (SAA), 7½-inch barreled “Cavalry Model” is loaded, one at a time, by bringing the hammer to half cock (second click), then opening the loading gate and inserting a cartridge. The cylinder is then rotated to the next chamber and the process repeated.

— Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company —

Empty casings are ejected, also one at a time, via manually pushing the ejector rod, housed under the barrel, through each chamber. Although somewhat slower than the Schofield, some officers reported that the single loading method of the Colt was not considered a detriment since most mounted pistol charges only saw a couple of rounds fired—thus the necessity of exposing the entire cylinder for a complete reload was not as critical.

In contrast, the 7-inch barreled, top-break framed Schofield had more intricate parts, due to its rapid reloading design. First the hammer is brought to the first click, allowing one to pull back the hinged latch at the rear of the top strap. Then, by pulling back the latch and simultaneously lowering the barrel and cylinder assembly, the extractor star in the cylinder’s center is raised enough to insert fresh cartridges, while ejecting only the spent casings.

Under ideal conditions this is surely a much faster way to reload, however when attempted from a possibly excited, plunging horse, as often encountered in the heat of battle, loaded cartridges still in the cylinder would sometimes hang up in it, causing a temporary jam that needed to be cleared manually. This writer has experienced both the speed of reloading a Schofield (originals and replicas) and cartridge hang-ups, while taking part in mounted cavalry re-enactments and cowboy mounted shooting competitions.

— Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company —

The Schofield’s shorter cylinder was unable to chamber the Army’s longer 40-grain black powder load with its 250-grain lead bullet cartridge. The S&W loading held 28 grains of black powder and a 230-grain lead projectile. Eventually, in 1875, in order to simplify ammunition supply and accommodate the Schofield, the Army began issuing the shorter cartridge known as the “Revolver Ball Cartridge, Caliber .45.”

Shooters who have handled originals or replica Schofields know that like a Swiss watch, it’s a tightly fit, precision handgun. After firing a few shots, it tends to experience cylinder drag from carbon buildup of black powder—even from some of the dirtier smokeless powder loadings, faster than with Colts. The extended firing by the SAA is due to having more space between the cylinder and base pin/frame, allowing for more carbon buildup.

While these advantages and disadvantages of the .45s were faced by the frontier Army, every soldier had his favorite sidearm. Ultimately both revolvers proved to be fine weapons, and were used extensively by the U.S. Cavalry during one of its most active periods in our history. Despite slight drawbacks to the designs of each arm, both the Colt and the Schofield served our horse soldiers well and each has an enviable record of rugged campaigning.

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.