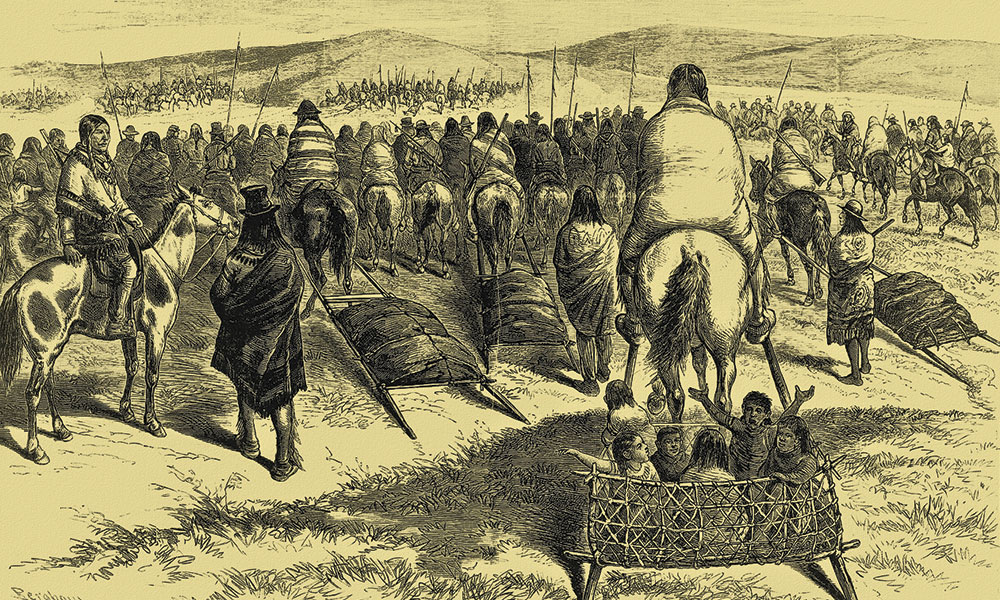

– Courtesy Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 9, 1877 –

The legend, the myth, the legacy of Crazy Horse didn’t end with his death. American Indians of several tribes—including some who opposed him in the last year of his life—hailed him as a hero and an exemplar of nobility and courage.

Crazy Horse’s legacy began shaping up when the Lakota leader played an important part in the Indian force that killed Lt. Col. George Custer and his men at Little Big Horn on June 25-26, 1876. Crazy Horse battled the U.S. Army for another six months. But the soldiers numbered too many, and they were determined to avenge the Custer loss.

Other Indian leaders, especially his Lakota compatriots Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, had surrendered years before. Each had his own reserved land. As the winter of 1876-77 got nasty, more of Crazy Horse’s followers gave up and pressed their leader to do the same.

On May 6, 1877, Crazy Horse surrendered at the Red Cloud Agency near Fort Robinson in northwest Nebraska. The Army promised him his own agency. This news didn’t thrill Red Cloud or Spotted Tail, who felt Crazy Horse was getting preferential treatment. They and their followers spread rumors that Crazy Horse was planning to escape.

That August, the Army asked Crazy Horse to lead his men in stopping Chief Joseph from escaping with the Nez Perce to Canada. Crazy Horse reportedly told officers that he would fight till “all the Nez Perce are killed.”

But Frank Grouard interpreted Crazy Horse’s statement as he would fight “until not a white man is left alive.” This set off Gen. George Crook, who ordered troops to arrest Crazy Horse and send him to Florida.

Crazy Horse, unaware that Grouard had misinterpreted his statement, surrendered at Fort Robinson on September 5. Once the Lakota leader realized that the Army was going to put him in jail, he resisted. A friend, Little Big Man, grabbed his arms from behind, but Crazy Horse pulled a knife and slashed his captor’s arm.

One soldier, historically identified as William Gentles, bayonetted Crazy Horse twice in the back. The war leader died just before midnight. Ever since, folks began invoking his name.

When about 200 Lakotas and American Indian Movement activists took over Wounded Knee in present-day South Dakota in early 1973, they claimed to be carrying out Crazy Horse’s work.

In the Spirit of Crazy Horse became the name of a book focused on the activist Leonard Peltier, who was convicted of killing two FBI agents during a June 1975 incident at Pine Ridge.

More recently, last year, Dakota Access Pipeline protestors claimed to be acting in the tradition of Crazy Horse.

A nearly 600-foot-tall sculpture memorial in the Black Hills named for Crazy Horse has been under construction for nearly 70 years. At least some Lakotas—including descendants of Crazy Horse’s family—object to the project.

As the history books approach the 150-year date of his death in the next decade, Crazy Horse will likely remain a controversial figure of influence.