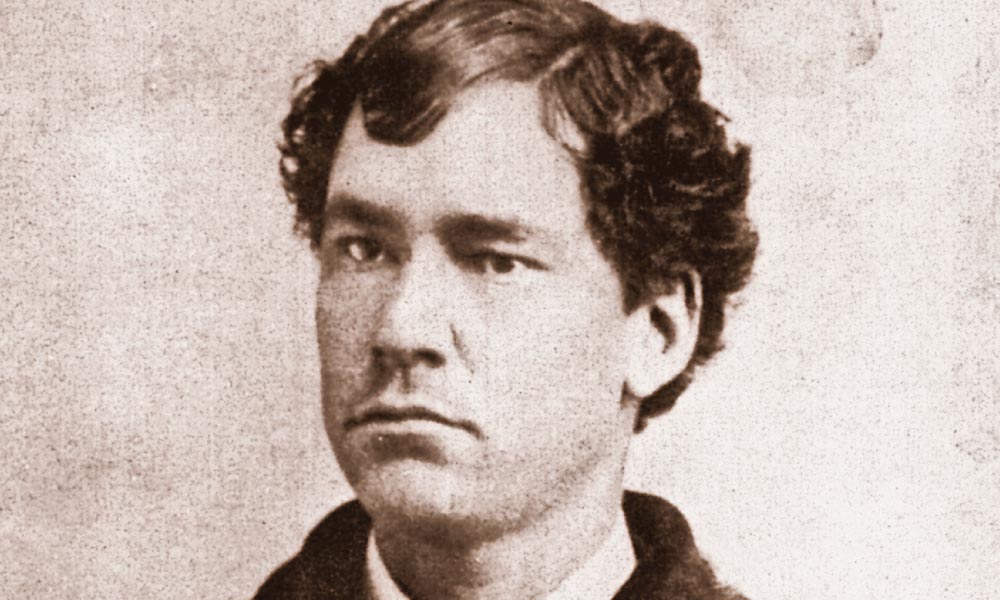

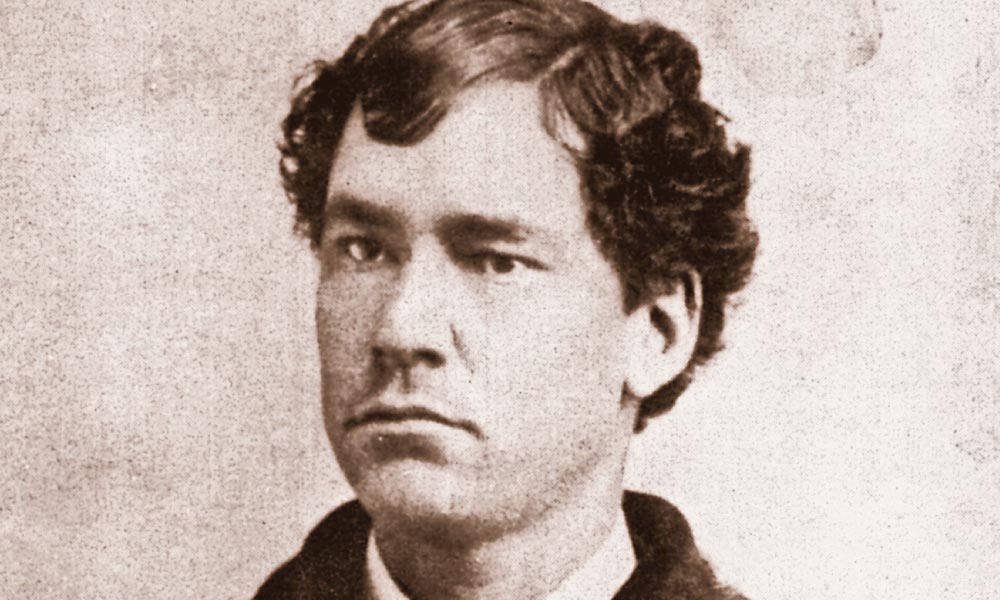

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

Who is New Mexico’s most famous lawman?

Don Bullis says it depends on whom you ask. Put that question to an Anglo, and—no surprise—the common answer will be Pat Garrett. But ask a Hispanic New Mexican and, as Bullis notes in his massive New Mexico Historical Biographies, “the answer will usually be Elfego Baca.”

Of course, Garrett garners most of the national glory—and gets Academy Award winners like James Coburn and Wallace Berry (whose Oscars did not come for their portrayals of the slayer of Billy the Kid)—while Baca is pretty much covered by Robert Loggia (who was only nominated for an Oscar, in 1985’s Jagged Edge) in some Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color episodes during the late 1950s. And those were reportedly (I wasn’t born in the 1950s) broadcast in black and white.

ELFEGO BACA GETS NO RESPECT

Hey, Sherriff Garrett’s claim to fame came from killing an outlaw, most likely armed with nothing more than a butcher knife, in a darkened bedroom in the middle of the night.

What did Baca do?

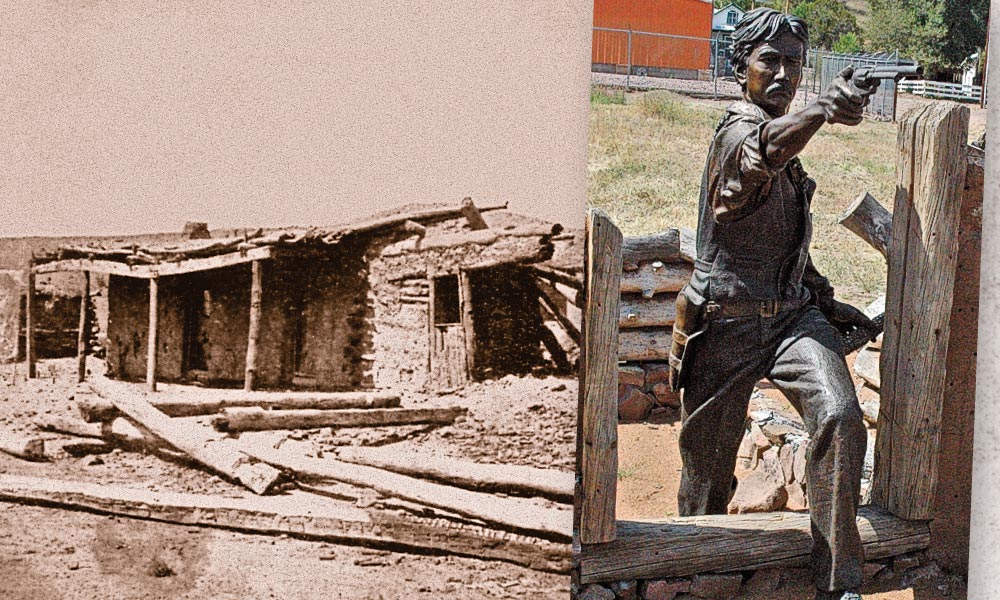

Well, if you buy the legend, Baca held off some 80 belligerent Anglo cowboys for 36 hours in a jacal in what is now Reserve, New Mexico, surviving an estimated 4,000 rounds of gunfire and even some dynamite.

A SHORT BIO

Born in 1865 in Socorro, New Mexico, Baca moved with his family to Topeka, Kansas, as a child. By 1880, he had returned to New Mexico. In addition to serving as a lawman, Baca would hang his shingle as an attorney and even be a private detective. Pat Garrett biographer Leon Claire Metz called Baca a “braggart,” and Baca definitely had a few warts on his resume.

But if there’s one lawman long overdue a Renegade Road, it’s Elfego Baca.

Metz writes of Baca: “He was, and is, controversial. He drank too much; he talked too much…; he had a weakness for wild women; he was often arrogant; and, of course, he showed no compunction about killing people.”

What’s not to like?

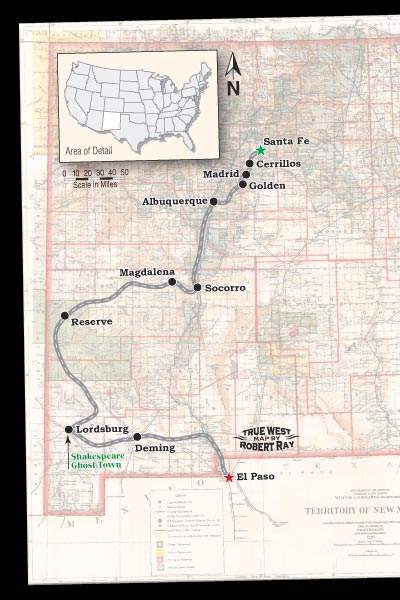

CITY DIFFERENT, TURQUOISE TRAIL

I’m starting in Santa Fe—and not just because I live here. Baca got here while he had a side job as a private detective after he has passed the bar and was a practicing attorney. Braggart? He was also cheap. One side of his business card read “Attorney at Law,” while the other side read “Private Detective, Discreet Shadowing Done.”

In 1891, Baca was in Santa Fe after a tip about an assassination plot. Powerful politician Joseph Ancheta was apparently the target (Thomas B. Catron, alleged member of the Santa Fe Ring, might have been another target), and was wounded by gunfire. Baca told authorities that a relative had overheard the plot, which came from state legislators. A few years later, Baca was again in Santa Fe, chasing an accused murderer.

His career as a Sam Spade wannabe isn’t glorious. The gunman who wounded Ancheta was never caught. No word on if Baca ever found that accused murderer.

His career as a Sam Spade wannabe isn’t glorious. The gunman who wounded Ancheta was never caught. No word on if Baca ever found that accused murderer.

There are other reasons to start in Santa Fe. The New Mexico History Museum, for one, where the Palace of the Governors photo archives hold at least five Baca images and the museum collection and exhibits are extraordinary. And it’s an easy drive to the Turquoise Trail.

The connection there has more to do with TV’s Baca than history’s Baca.

That Disney show, The Nine Lives of Elfego Baca, was filmed in Cerrillos, which boomed in the late 1870s as a mining town. You might recognize the town from another movie. It dubbed for Lincoln in Young Guns.

Follow the Turquoise Trail through historic and quirky Madrid, historic and picturesque Golden and touristy Sandia Park before turning east to Albuquerque, where you should walk around Old Town Albuquerque, check out the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History and visit Baca’s grave at Sunset Memorial Park.

THE ALBUQUERQUE YEARS

In 1906, Baca moved to Albuquerque, where he would become publisher and manager of the Spanish-language newspaper La Opinion Publica and help form New Mexico’s first chapter of the Spanish-American Alliance. He campaigned for statehood, campaigned for public office, got involved in a few scandals and oversaw the hanging of Demecio Delgadillo in 1913. He did the latter job because a friend, Sheriff Perfecto Armijo, did not enjoy that part of the job. But Baca? His title was bastonero (“master of ceremonies”), and after the execution, he said, “Gentlemen, this is one of the nicest hangings I have ever seen. Everything went off beautifully.”

If you believe Baca, he even hung out with Billy the Kid as a teenager in the early 1880s and witnessed Marshal Milton J. Yarberry, Albuquerque’s first town lawman (loosely speaking) kill a man. Yarberry would also hang in a grisly execution overseen by Armijo, which might explain why Baca had to fill in for the sheriff in 1913.

Baca spent his last years quietly in Albuquerque, died on August 27, 1945, and was buried at Sunset Memorial Park.

From Albuquerque, drive south to Socorro.

SOCORRO AND A SHOOTOUT

As a teenager in Socorro but having spent much of his youth in lily-white Topeka, Baca spoke Spanish “picked up from a Spanish household and diffused through the roughhewn English of a Kansas community,” biographer Kyle Crichton wrote.

Baca worked on an uncle’s ranch northeast of town, and in his later years he would serve as county clerk, mayor, district attorney and even school superintendent. He would be admitted to the bar in Socorro in 1894 and become a junior partner a local law firm. But Socorro is also where Elfego Baca pinned on his first badge.

Although he might have served on a posse in 1883, Baca’s legend was born in 1884.

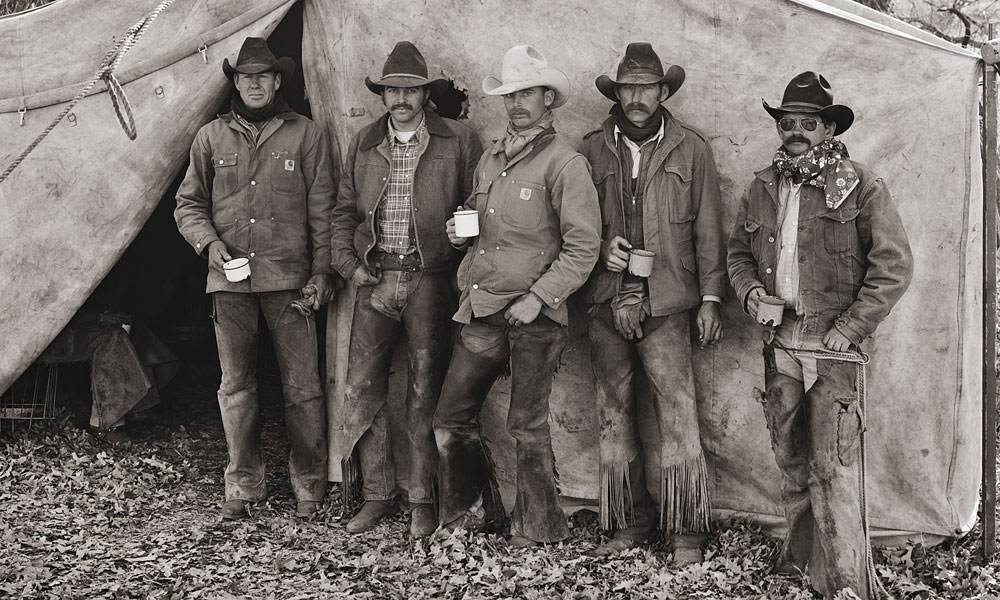

Deputy Sheriff Pedro Sarracino arrived in Socorro, telling how Anglo cowboys were tormenting Hispanics in the “Frisco Plazas” (Upper, Middle and Lower San Francisco plazas), roughly 130 miles west. Baca rode to help, and was deputized by Sheriff Pete Simpson.

“I will show the Texans there is at least one Mexican in the county who is not afraid of an American cowboy,” he reportedly said—and then lived up to his word.

James Muir’s sculpture, Elfego Baca—One Man, One War, honors Baca in Reserve. The plaque nearby tells the story:

“…Baca observed one cowboy butting another one on the head and firing several rounds with his pistol. Justice of the Peace Lopez stood by hopelessly, saying the Slaughter outfit had 150 cowboys on their payroll and could not be stopped. Determined and fearless, Baca promptly arrested the cowboy. A large group of cowboys gathered and demanded his release. Baca shot into the group wounding one man and they dispersed. But the following day, 80 enraged ranch hands rode into the town, intent on freeing the arrested cowboy and avenging the indignity of his arrest. A trial was held and the cowboy was released. Baca, sensing a gunfight, retreated to a jacal belonging to Geronimo Armijo and barricaded himself inside. Baca kept his six-shooter blazing for 36 hours, pausing just long enough to cook some tortillas and beef stew. Protected by mud and picket walls, a sunken floor and an icon of Nuestra Senora Santa Anna, Baca braved dynamite and some 4,000 rounds of gunfire shot in his direction by the Texas cowboys.

“On the third day, Baca agreed to give himself up to Deputy Ross from Socorro but refused to turn over his guns. Baca, unscathed throughout the gunfight, had killed two cowboys and wounded two more.

“The atrocities stopped.”

GUNFIGHT IN EL PASO

Baca would be tried, but acquitted. He married, had a son and five daughters.

As a peace officer, he brought others to justice. And he spent a lot of time in El Paso. Stop and visit Lordsburg, Shakespeare and Deming on your way south and east.

The Frisco Shootout wasn’t Baca’s only scrape.

In El Paso, during the Mexican Revolution, Baca met Celestino Otero, who, Metz notes, “supported a different faction” of the revolution. When Baca stepped out of his car, Otero shot him in the groin. The wounded Baca put two bullets through Otero’s heart, and was acquitted of murder by an El Paso jury.

Hey, Pat Garrett. Top that.

Okay, I’m giving Pat a hard time. Besides, to get back to Don Bullis, who started this affair, I’ll give him the final word.

“Both men lived notable lives.”

Actually, Johnny D. Boggs’s favorite Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color episode was Swamp Fox. No, make that The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh.